A team of researchers at the USMARC, Iowa State University, Hanor Co. and Smithfield Hog Production suggests putting a greater emphasis on gilt development to drive sow lifetime productivity.

October 31, 2018

When thinking about all of the factors that tie into a sow’s lifetime productivity, one of the oft-overlooked aspects is the development of the gilts that will lead the performance of a herd, hopefully for a long time.

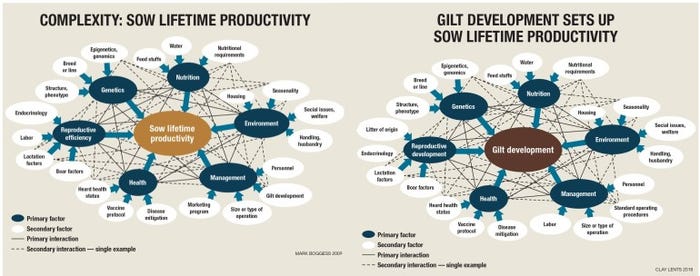

Gilt development has been looked at as a secondary factor of a sow’s lifetime productivity, along the lines of a marketing program, size and type of operation and personnel — all of which feed the primary factor of management. The tide is turning to start giving the gilt, and her development, more respect.

“We’ve always thought of gilts as being fairly cheap,” said Clay Lents, research physiologist with the USDA U.S. Meat Animal Research Center at Clay Center, Neb., “but it takes her two-and-a-half to three parities to make up the cost of her raising, so it’s not necessarily cheap.”

With that in mind, a team of researchers at the USMARC, Iowa State University, Hanor Co. and Smithfield Hog Production suggests putting a greater emphasis on gilt development as a main driver of sow lifetime productivity.

Lents presented research by the team during the Allen D. Leman Swine Conference in September in St. Paul, Minn.

Clay Lents said there’s a new way of thinking about the role gilt development plays in the complex web of sow lifetime productivity. The traditional matrix of SLP is shown on the left, but Lents feels the redesigned matrix shown on the right more accurately portrays how gilt development setsup SLP.

Early puberty and fertility

Early sexual maturity is critical for sow lifetime productivity, and age at puberty, “or that first HNS [heat no serve], is the first indicator of a gilt’s reproductive potential,” Lents said. Early sexual maturity is important because age at puberty is positively associated with other indicators of fertility and productivity, he said, such as being more fertile at each estrus and subsequent farrowing; they have shorter wean-to-estrus interval and more regular farrowing intervals, and thus would be less likely to be culled for reproductive reasons, such as having more nonproductive days.

“They tend to stay in the herd longer and produce more pigs — not just over their lifetime, but also in each litter,” he said. “I think it’s an important trait, and one of the few reproductive traits that is moderately heritable, and that’s an important consideration as well.”

Age at puberty occurs over a large range of lean growth rates and backfat thicknesses, making it challenging to use such measures as indicators of gilts’ potential. “In general, gilts with the highest growth rates accumulate more backfat, and they tend to cycle earlier,” he said.

As a rule, it is ideal for gilts to gain more than 600 grams per day (1.1 pounds) of lifetime growth from rate from birth to time of selection, with a 300-to 330-pound body weight at time of breeding. “That’s an optimal weight range to avoid some of those larger gilts.”

Keeping weight down key

Avoiding gilts that are heavier throughout their life will save the producer and the females themselves a lot of headaches down the road. Heavier gilts (over 140 kilograms at first estrus and over 140 kg at breeding) run a higher risk of lameness and injury, require higher maintenance costs in feed and tend to be culled earlier from the herd, and thus have lower lifetime productivity.

Different schools of thought exist on feeding gilts to get ready for a long productive life in the herd, either feeding ad libitum or an energy-restricted diet. “People typically feed gilts ad lib, but recommendations are to slow their growth at some point in time,” Lents said, pointing to a feeding trial of 15% energy restriction that looked at the effects of a Parity 1, 2 or 3. “It shows there was no effect on Parity 1, but gilts that were on the energy-restrictive diet showed a greater probability of having a second or third litter.”

Lents said such trials show a few things that go against conventional wisdom or thinking of the past. First, gilt development has traditionally stopped at HNS or after the first parity, and “really proper gilt development is accumulation of a lot of little things that provide small advantages at each step, and that begins to show up the further into production that you go.”

This means that producers, and the industry as a whole, need to take a more long-term view at feeding gilts for long-term productivity.

A National Pork Board SLP Research Consortium sought to find the long-term benefits to reducing growth of gilts in development and what the best diets are to be used. Those questions had to be answered in a setting that would be applicable in the real world using large numbers of animals under commercial conditions, where gilts would have ad libitum access to feed made up of practical diets of ingredients that are readily used and readily available.

Chris Hostetler, NPB director of animal science, informally surveyed producers for what they typically feed gilts, finding the diets consisted of metabolizable energy (ME) of 3,200 to 3,300 kilocalories per kilogram, and SID (standard ileal digestible) lysine levels between 0.8% and 1% in the finisher ration.

Energy, lysine use studied

From this information, six diets were formed, exhibiting three levels of energy and two levels of lysine. ME varied from the control diet by 85%, 100% and 115%. Each of those three ME levels were paired with lysine levels that varied 85% from the control diet. Three similar ME diets were paired with 100% lysine variance from the control diet. A total of 1,221 gilts were fed from 100 to 260 days of age, with 18 pigs per pen in two grow-finish barns in Iowa.

The gilts in this study were shipped for slaughter, after which they were studied for reproductive development. Results showed these diets had no effect on body weight, and the high-ME diets resulted in about a 10% increase in backfat, “but there’s some question as to if that’s biological-relevant,” Lents said.

As expected, the pigs fed the lower ME-diet compensated by eating more to meet the ME intake for growth. Lents said this first trial indicates there was limited opportunity to change ME and alter growth or composition of gilts in a biologically meaningful way. It also shows that a 15% reduction in lysine failed to affect growth or development, “suggesting that we can potentially reduce lysine in the diet of developing gilts.”

Equally as expected, Lents said upon slaughter of the gilts from this trial, the rations didn’t appear to have an effect on uterine development or ovary function. Two further feeding trials were initiated to take a more strategic look, developing high-lean, medium-lean and low-lean diets for growers (100 to 142 days) and finishers (143 to 220 days) by reducing the levels of lysine even further compared to the first trial. “As we did that, we increased fiber in the diet by adding wheat midds and corn germ to try to compensate to prevent the gilts from adjusting their feed intake, and adjusted energy level by adding grease,” he said.

In Trial 2, 641 LW x LR maternal-line gilts were fed from 100 to 220 days of age and were studied for feed intake, body weight and body composition. Trial 3 consisted of 3,024 LW x LR maternal-line gilts fed from 100 to 200 days of age, and also studied for feed intake, body weight and body composition. At 28 weeks, the gilts were moved to sow farms and placed on a gestation diet. These gestation diets varied by sow farm destination; some were fed ad libitum, and others were fed 4 pounds per day.

High-lean best

Regardless which diet these gilts were on (low, high or medium), Lents said they showed acceptable growth to meet the breeding targets, even though those on the high diet had the higher average daily gains, and those on the low diet had the lowest ADG.

Lents said researchers learned from these trials “that we were able to successfully alter growth rates and body composition in development, but we had to add fiber to do that. You have to limit access to feed, or you have to have some intake-limiter in your diet to achieve that.”

Despite reducing lysine “quite a bit” in the rations, “we still achieved sufficient growth and body composition in gilts for good reproductive performance,” he said.

Trials 2 and 3 also included boar stimulation, starting when gilts are 160 days of age — which should be physiological maturity. Vasectomized boars were used for 10-minute daily contact in pens, in four pens per day with 20 to 24 gilts per pen. Boars rotated among pens daily, resting every other day. “Ideally, we would have more time of exposure each day, and the number of gilts was too high. It would be best to have only 15 gilts per pen for maximum exposure,” Lents said.

Research revealed that higher-growth gilts respond to boars sooner and have an earlier age of puberty. Also, despite adequate growth and development, response to boars was inadequate. “This has important implications for use of PG600, and it emphasizes the importance of gilt stimulation protocols. I also think we under-appreciate the effects of disease on reproductive development,” he said.

Even though gilts continue to grow, Lents said they are losing body condition in breeding, so it is imperative to continue proper nutritional management of gilts after leaving gilt development all the way through subsequent parities.

You May Also Like