Hog Nutrition

thumbnail

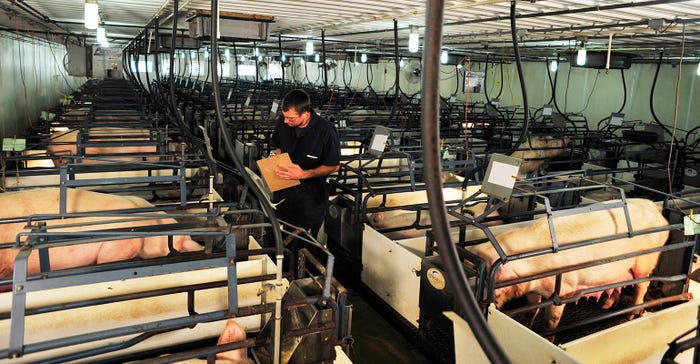

Livestock Management

Copper beads in pig feed may improve swine gut healthCopper beads in pig feed may improve swine gut health

In lab experiments, copper shows antimicrobial properties, including against pathogens like Salmonella.

Subscribe to Our Newsletters

National Hog Farmer is the source for hog production, management and market news