SVA continues to circulate in breeding herds for a significant amount of time after clinical signs.

June 8, 2021

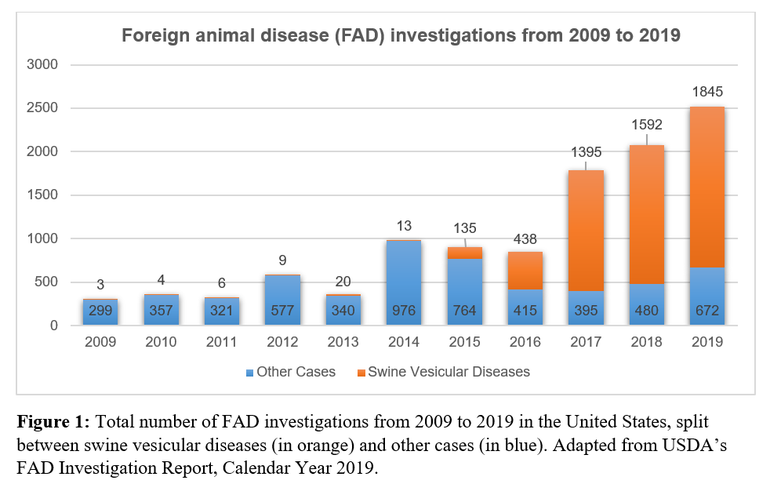

Senecavirus A (SVA) is well known in the United States (U.S.) industry for causing a vesicular disease — visually indistinguishable from other high-impact and government-monitored vesicular diseases, such as foot-and-mouth disease (FMD). For this reason, this virus has been responsible for a rampant increase in the number of foreign animal disease (FAD) investigations in the U.S. after the initial SVA outbreaks in swine operations in 2015 (Figure 1).

In addition to its potential to disrupt business, SVA has also been linked to high neonatal mortality and diarrhea during outbreaks. However, it is still unclear how SVA transmits between and within pig farms. Thus, it is not well understood how to efficiently monitor and control this disease in order to prevent further losses and confusion with the other market-disrupting vesicular diseases. One critical question that is yet to be answered is how long the virus remains active inside a sow farm after its introduction, as vertical transmission of the virus leads to having infected litters carrying the virus down the production flow.

At the University of Minnesota (UMN), we decided to begin addressing this question and conducted a study funded by the American Association of Swine Veterinarians Foundation. With help from two production systems and two veterinary clinics, processing fluids samples from 10 sow farms were collected and tested by PCR for SVA at the UMN’s Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory. Additionally, one farm had semen and tissues from heat check boars tested in order to assess their role on the persistence of the virus in the breeding herd after an SVA outbreak.

All farms were monitored after the outbreak for a period ranging from 16-26 weeks, with some farms having samples collected even before SVA signs were detected. The virus was detected in processing fluids from all farms and intermittent detection ranged between 1-21 weeks after the first SVA clinical signs were seen, for an average of 11.8 weeks. Interestingly, one farm was SVA positive three weeks before clinical signs of SVA were evident, while three and one farms were positive two and one weeks before SVA signs were seen, respectively

Heat check boars could be potentially acting as a source of SVA infection to naïve gilts and sows over time after and outbreak. In two semen collection time-points, seven out of nine and one out of 16 tested boars at seven and 18 weeks after the outbreak had SVA positive semen, respectively. Furthermore, the boar with SVA-positive semen in the second collection time-point was euthanized and had its testicles tested at 22 weeks after the outbreak. Testicular tissues contained a significant amount of SVA genetic material.

The data collected in this study shows that SVA continues to circulate in breeding herds for a significant amount of time after clinical signs have been detected. Considering that SVA signs in breeding herds are usually seen for two weeks after the outbreak, producers and practitioners should be cautious when classifying the herd as stable by consistently weaning SVA-negative piglets. Our study clearly demonstrated that absence of clinical signs does not necessarily indicate that the virus is no longer being transmitted within the herd. Processing fluids have been successfully used in the monitoring of PRRS in disease elimination protocols, and it appears that this tool might also be implemented for the control of SVA. Heat-check boars also appear to play an important role in the persistence of SVA in a sow farm, so strategic sampling and testing of these animals is advised.

This study contributes to the SVA-epidemiology knowledge in sow farms. The virus is endemic in the U.S. swine industry and is constantly causing problems to swine producers, governmental animal health agencies, diagnostic laboratories and processing plants. Further understanding SVA transmission and persistence in sow farms can lead to the development of strategies to reduce and stop weaning SVA-positive piglets, helping reduce SVA incidence in pig production systems.

Sources: Guilherme Preis, DVM; Fabio Vannuci, DVM, MS, PhD; Cesar Corzo, DVM, MS, PhD; University of Minnesota, who are solely responsible for the information provided, and wholly own the information. Informa Business Media and all its subsidiaries are not responsible for any of the content contained in this information asset.

You May Also Like