Pigs with biscuit enrichment that had no attractant had most promising early nursery daily feed intakes.

October 21, 2021

The time immediately after weaning is one of the most stressful periods in a pig's life. Weaning typically occurs around 19 to 23 days of age on most U.S. commercial farms. This early weaning age may provide some pig advantages, such as improved health (de Grau et al., 2005), but pigs experience multiple stressors, such as separation from their dam, mixing with unfamiliar pigs, transportation to a new facility, and abrupt transition from milk to solid feed (Dybkjær, 1992; Weary et al., 2008). These stressors may result in increased aggression (Hwang et al., 2016), leading to injuries (D’Eath, 2005) and low feed intake (Wensley et al., 2021). One area that needs to be explored further is the use of environmental enrichment to enhance early feed intake and help with weaned pig transition.

Environmental enrichment is a biologically relevant modification to an animal’s environment with the aim to improve its functioning (Newberry, 1995). We know that pigs are attracted to things that smell and can be easily chewed and destroyed (Van de Weerd et al., 2003). Using straw, rubber toys, and ropes have helped reduce aggression (Apple and Craig, 1992; Lahrmann et al., 2018), but these have not consistently resulted in improved performance such as growth, feed intake, and gut-health measures (Oostindjer et al., 2010).

Therefore, we were interested to see how a nutritional enrichment “biscuit” would influence weaned pig behavior at the feeder and improve early feed intake and growth performance.

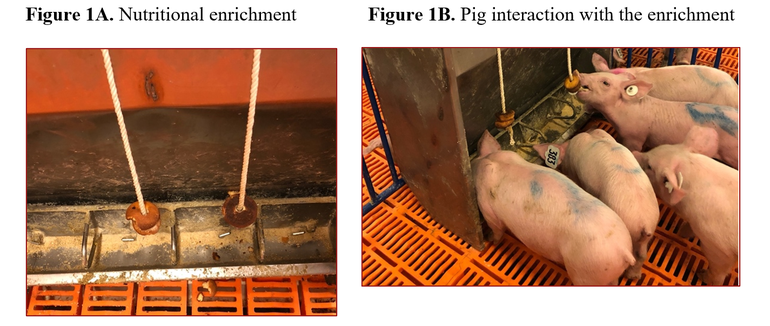

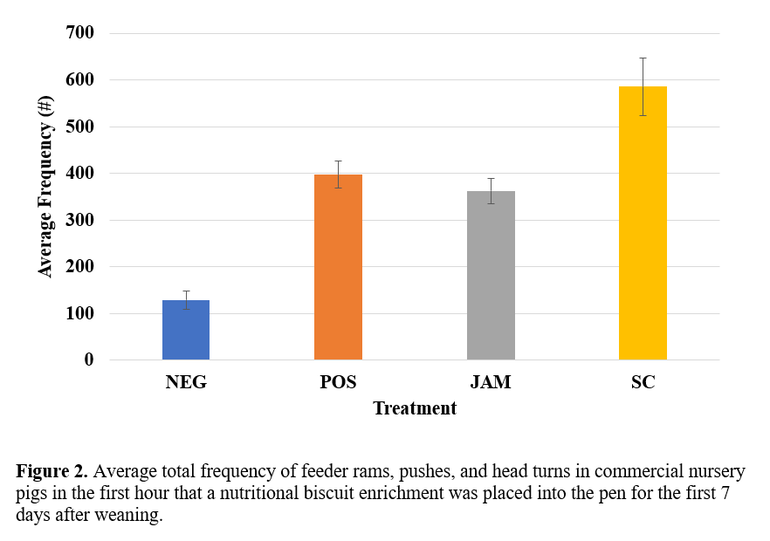

For the project, eighty, mixed-sex pigs (Camborough [1050] X 337, PIC, Hendersonville, TN), 19 to 24 days of age (approximately 6 kg [13 lbs.]), were housed in eight commercial nursery pens (10 pigs/pen). Four treatments were compared: (1) biscuit with a fecal semiochemical attractant (SC), (2) biscuit with a sugary attractant (JAM), (3) plain biscuit (POS), and (4) no biscuit (NEG). Biscuit ingredients came from a starter nursery diet. Each enrichment pen received four biscuits suspended from two ropes at the feeder for the first seven days after weaning and were hung at pig eye level (Figures 1A & 1B).

Using collected video, each of the eight pens of pigs was watched for one hour after placement of the enrichment biscuits over the first seven days after weaning. Every time a pig rammed, pushed, or turned their head towards another pig with or without biting around the feeder was recorded. All pigs were individually weighed on Day 0 and 7 and all feeders were weighed daily to assess daily feed disappearance so that ADG and ADFI could be calculated. Over this test period, pigs in all pens were fecal scored using a 0 to 3 scale, where: Score 0 = normal/solid, Score 1 = semi-solid/soft, Score 2 = semi-liquid, and Score 3 = liquid/diarrhea. Finally, morbidity and mortality data were collected.

Findings

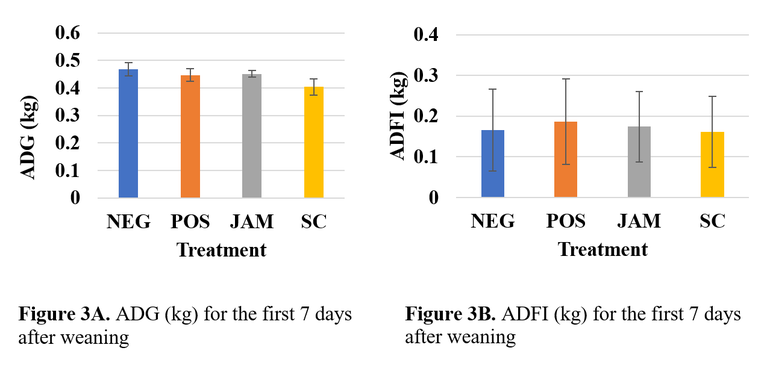

Over the first seven days after weaning, the average total frequency of feeder rams, pushes, and head turns was highest in pigs exposed to the biscuit with the fecal semiochemical (SC), and lowest in pigs with no biscuit enrichment (NEG, Figure 2).

Regardless of enrichment treatment, the average length pigs engaged in ramming, pushing, or head turning was very short (≤1 second). Initially, the average total frequency of pigs engaged in ramming, pushing, and/or head turning with or without biting may seem surprising, and one might conclude that this type of enrichment is more of a hindrance than a help. However, we need to place this proof-of-concept study into context: (1) when ramming, pushing, and/or head turning with or without biting occurred at the feeder, they were very short and, (2) they did not result in pigs being removed for injuries. It would also be incorrect to conclude that pigs with no enrichment were not engaging in these behaviors during this time because they were being conducted in other areas of the pen and were not counted in this study.

All pigs consumed small quantities of feed (less than 200 g/d) over the first seven days after weaning, which is typical of what is reported commercially (Figure 3A). Interestingly, when considering ADFI, pigs with a biscuit that had no attractant ate the most (Figure 3B). This is a promising result and warrants further investigation.

It was pleasing to see that the additional nutritional enrichment did not upset the pigs’ GI tract, as pigs on average had a fecal score of 2. Finally, no pigs were removed for health-related issues or died in the first seven days after weaning.

At a time where customers and consumers are asking questions about the pig’s quality of life and enriching their living environment, this enrichment biscuit may be a viable option. It is cost effective, easy to implement, and fits well into commercial North American nursery systems. Therefore, this proof-of-concept study has yielded intriguing results that need further investigation commercially.

Summary points:

Biscuit enrichment at the feeder did not translate into pig removal from ramming, pushing, and/or head turning with or without biting injuries.

Pigs with a biscuit enrichment that had no attractant had the most promising early nursery daily feed intakes.

This project was supported by the National Pork Board, the US Pork Center of Excellence, Iowa Farm Bureau Federation, and the Foundation for Food and Agriculture Research Grant #18-147. Partial funding of Dr. Johnson’s salary is supported by the Department of Animal Science, College of Agriculture and Life Sciences at Iowa State University, and the US Department of Agriculture.

Sources: Cassandra Stambuk, Emiline Sundman, Grace Mercer, Nicholas Gabler, Locke Karriker, Suzanne Millman, Kenneth Stalder, Anna Johnson, Iowa State University, who are solely responsible for the information provided, and wholly own the information. Informa Business Media and all its subsidiaries are not responsible for any of the content contained in this information asset.

Resources

Apple, J. K. & Craig, J. V. (1992). The influence of pen size on toy preference of growing pigs. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 35, 149-155. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-1591(92)90005-V

D’Eath, R. B. (2005). Socialising piglets before weaning improves social hierarchy formation

when pigs are mixed post-weaning. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 93(3–4), 199–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2004.11.019

de Grau, A., Dewey, C., Friendship, R., & de Lange, K. (2005). Observational study of factors associated with nursery pig performance. Canadian Journal of Veterinary Research = Revue Canadienne De Recherche Veterinaire, 69(4), 241–245.

Dybkjær, L. (1992). The identification of behavioral indicators of stress in early weaned piglets. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 35, 135-147. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-1591(92)90004-U

Hwang, H. S., Lee, J. K., Eom, T. K., Son, S. H., Hong, J. K., Kim, K. H., & Rhim, S. J. (2016). Behavioral characteristics of weaned piglets mixed in different groups. Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences, 29(7), 1060-1064. https://doi.org/10.5713/ajas.15.0734

Lahrmann, H. P., Hansen, C. F., D'Eath, R. B., Busch, M. E., Nielsen, J. P., & Forkman, B. (2018). Early intervention with enrichment can prevent tail biting outbreaks in weaner pigs. Livestock Science, 214, 272-277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.livsci.2018.06.010

Newberry, R. C. (1995). Environmental enrichment: Increasing the biological relevance of

captive environments. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 44, 229–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-1591(95)00616-Z

Oostindjer, M., Bolhuis, J. E., Mendl, M., Held, S., Gerrits, W., Van den Brand, H., & Kemp, B. (2010). Effects of environmental enrichment and loose housing of lactating sows on piglet performance before and after weaning. Journal of Animal Science, 88(11), 3554-62. https://doi.org/10.2527/jas.2010-2940

Van de Weerd, H. A., Docking, C. M., Day, J. E. L., Avery, P. J., & Edwards, S. A. (2003). A systematic approach towards developing environmental enrichment for pigs. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 84(2), 101-118. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-1591(03)00150-3

Weary, D. M., Jasper, J., & Hötzel, M. J. (2008). Understanding weaning distress. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 110(1-2), 24-41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2007.03.025

Wensley, M. R., Tokach, M. D., Woodworth, J. C., Goodband, R. D., Gebhardt, J. T., DeRouchey, J. M., & McKilligan, D. 2021. Maintaining continuity of nutrient intake after weaning. II. Review of post-weaning strategies. Translational Animal Science, 5, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1093/tas/txab022

You May Also Like