It seems logical to me that, even with robust flows of bacon to consumers and bellies to bacon cookers, the stocks can be replenished rather quickly if the market says they need to be replenished.

February 6, 2017

The big news nearly everywhere last week was the sheer terror of a possible bacon shortage? Yes, there we went again, but this time it wasn’t the doing of some Brits with too much time on their hands.

This “shortage” sprang from an Ohio Pork Producers Association press release that cited USDA reports as indicating a possible shortage of bacon and referred readers to website called BaconShortage.com. Later in the day, they released a statement claiming to have never said there was a shortage and disavowing any responsibility for the media’s latching on to the “shortage” story. I’ll let our readers reconcile “we never said there was a shortage” with operating a website with the name “BaconShortage.com.” I don’t know about yours, but my kids would have been in big trouble for the slight inconsistency of those words.

“But cold storage stocks are low so there must be a shortage,” you say. Not so fast. Let’s consider what the term “shortage” means in the context of economics. And let’s start with the facts.

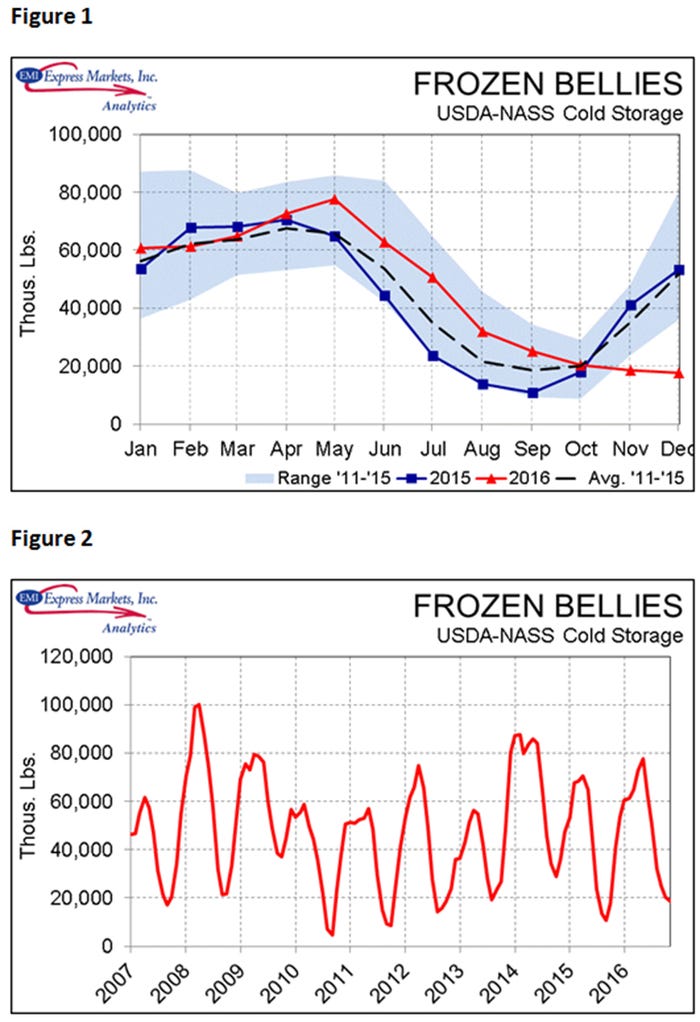

The Dec. 31 inventory of pork bellies was 17.759 million pounds, down 66.7% from last year’s 53.392 million pounds. It is easy to see from Figure 1 that this level and the change from last year are indeed unusual. The Dec. 31, 2016, inventory was the lowest belly inventory on Dec. 31 since 1957. “Bellies Stocks Are Lowest in 50 Years!” the headlines trumpeted.

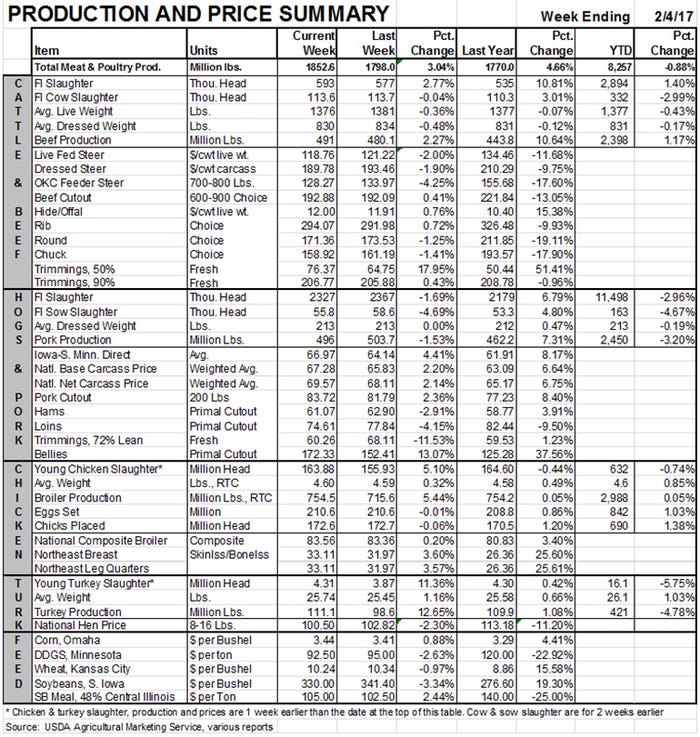

But the truth is that bellies stocks have been lower than this on many occasions. Just not in December! See Figure 2.

So are we in dire danger of running out of bacon?

Second fact: An inventory can be replenished by production. Compare the 17.759 million pounds of bellies stocks to the fact that U.S. packers will produce roughly 74 million pounds of bellies this week. It seems logical to me that, even with robust flows of bacon to consumers and bellies to bacon cookers, the stocks can be replenished rather quickly if the market says they need to be replenished.

And in that last statement lies the real item to remember: Properly working markets solve “shortages” quickly. Especially shortages that really aren’t shortages.

In economics, a “shortage” — or the unavailability of a good — occurs only in very short time periods and almost universally in instances where markets will not allow the quantities demanded by consumers to match the quantities supplied by producers. Prices will take care of “shortages” pretty quickly if allowed to function and the bellies price is doing just that.

USDA’s pork belly primal has risen from just of $100 per hundredweight in November and December to $172.33 last week. That price rise will slow the rate of usage by bacon processors. The quantity of bacon being produced will decline and processors will mark up prices to cover the higher bellies cost. Retailers and restaurants will charge more for bacon, slowing consumer usage there. The result will be that more bellies will be put in freezers as the number of hogs grows and prices “ration a limited supply.”

The mechanism works so well that I don’t think we will hear of anyone running out of bacon, thus meaning that any “shortage” will never be seen by buyers. Can a shortage be a shortage if no one ever sees an empty shelf? I don’t think so.

So no foul, no harm, right? Not really. The good folks at the Ohio Pork Producers Association are very fortunate that the futures market did not react — or react violently — to their story. Markets — and especially futures markets — are fueled by information. Information like this can impact the value of millions of positions and those who were holding short positions would have been hurt by this news, perhaps to the tune of millions of dollars.

“But the market didn’t react so nobody got hurt,” you say. Perhaps. But what if the market would have fallen sharply last Wednesday without this “news”? The decline would have given all of those short position holders a chance to turn a profit. A chance they never had because of this “news.” The fact that futures prices did not change does not mean that the market was not impacted.

Trade associations must be careful about releasing “market-sensitive” information since doing so, especially if it plays loose with the facts or is actually false, could run afoul of anti-trust laws. The Department of Justice watches trade associations very closely since they are, by definition, associations of competitors. “But we are just a group of little old hog farmers!” some would protest. To which I ask “And what if the association of little old pork packers released a statement that there are going to be WAY TOO MANY HOGS this year?” (I don’t even use the association’s name here as I know how sensitive they are to these kinds of things.) I’m betting neither producers nor the DOJ would be too enamored with that kind of public statement even if it was based 100% on fact.

I urge all producers and producer associations to stick to the facts and to the context of the facts. While we all want stronger markets we have to be careful to remain above reproach when it comes to possible manipulation. If we expect that of others, we must demonstrate it ourselves. You know, that Golden Rule thing.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like