Visit with your management and marketing advisers now to develop a plan to protect your business — and hopefully still allow opportunities to profit should things get better in the second half of 2019.

March 4, 2019

Today is another red-letter day for the U.S. pork industry. The latest slaughter plant began operations this morning in Wright County, Iowa. The Prestage Foods plant has (no more future tense for this discussion) an initial one-shift capacity of 10,000 head per day. It will operate well below that level initially, of course, as the plant and equipment are proven and workers are trained.

That last item will be a challenge. Iowa’s unemployment rate in December was 2.5%. Wright County’s was 2.2%. An executive with a company that opened a new hog plant a few years back told me “Steve, I can tell you that you don’t want to be the outfit that hires the last 3% of the labor force. There’s a reason most of those people are unemployed.”

We sincerely hope this works better for Prestage than it did for that company but labor — and quality labor — is an issue virtually everywhere. No matter how much you pay, work in a hog plant involves killing animals and cutting them into parts. Those are not skills that schools teach to prepare students for “jobs of the future.” It is tough work. I immensely appreciate the people who do it, but facts are facts.

We wish our friends at Prestage the best in their new venture. The family has been in the turkey business for many years. Their turkey enterprise includes harvesting and processing birds and selling finished product, so they are not novices to this meat thing. Best wishes, Bill and sons!

The Prestage Foods plant is the last of the current list of pork packing plant openings. It comes on the heels of one new plant in 2015 (MoonRidge Pork in Missouri which subsequently closed), one plant in 2016 (Prime Pork in Minnesota, 5,100 head capacity) and two plants in 2017 that added 22,200 head of one-shift capacity in one day. The Clemens Food Group in Michigan is running near 10,000 head per day (capacity is 12,000). The Seaboard-Triumph plant in Sioux City, Iowa, filled its one-shift capacity of 10,200 head per day in about a year but has struggled some to get B-shift full. Our sources indicate that STF has backed off second shift operations to 5,000 head or so in recent weeks.

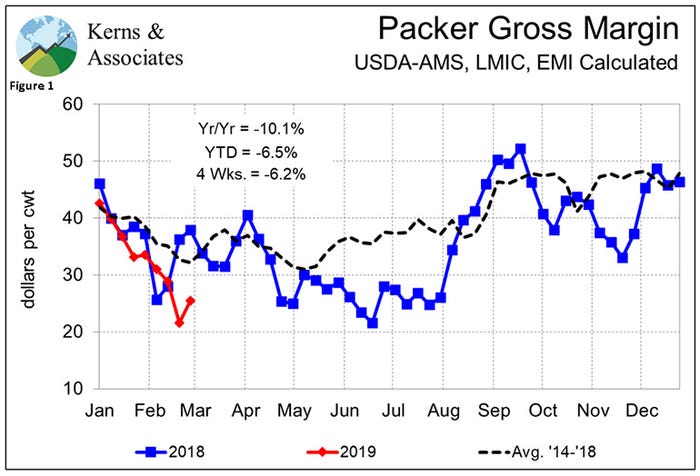

Still, U.S. capacity is roughly 9.5% larger than it was the fall of 2015. That fall and the next, high capacity utilization had negative impacts on live prices. The impacts could have been much larger in 2016 if packers had not made a conscious decision to not take prices lower. They could have done so. Producers had hogs that had to move at whatever price was offered. They had no choice. But some foresighted packers decided the damage — economically for producers and politically for packers — would be too large.

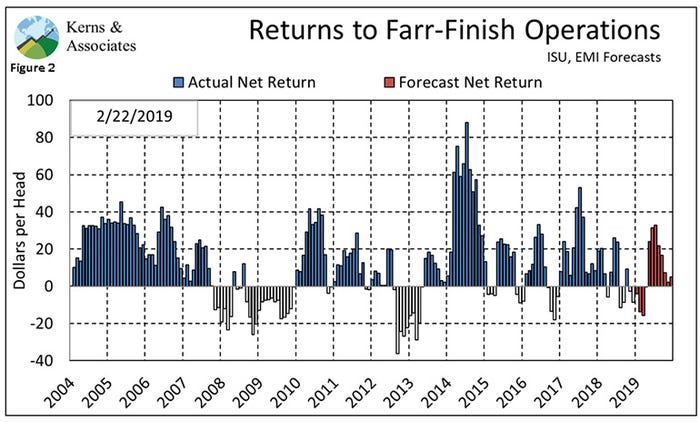

Some producers are again facing serious financial challenges. Our computations indicate that even the lowest-cost 20% or so of producers have made money in only seven of the past 14 months. Average producers, which we believe have costs about $5 per hundredweight or $10 per head higher than that low-cost 20%, have lost money in 10 of the past 14 months. At current hog, corn and soybean meal future prices the low-cost group could lock in about $9 per head profits for this year while the average producer would be near breakeven.

All of those figures are based on Iowa State University’s Estimated Costs and Returns for Iowa farrow-to-finish producers. But they will not match the figures posted on ISU’s website because we use a different selling price. ISU used the average negotiated base price in Iowa-Minnesota. We use the national average net price that includes premiums as well as formula-priced hogs and hog prices with packers based on CME Lean Hogs futures prices. Our profit figures are higher than ISU’s, but we think they are more representative since the sales price represents all hogs sold and not just the minority sold through negotiated trades. Negotiated prices tend to lag the weighted average across all pricing methods when hog supplies are large.

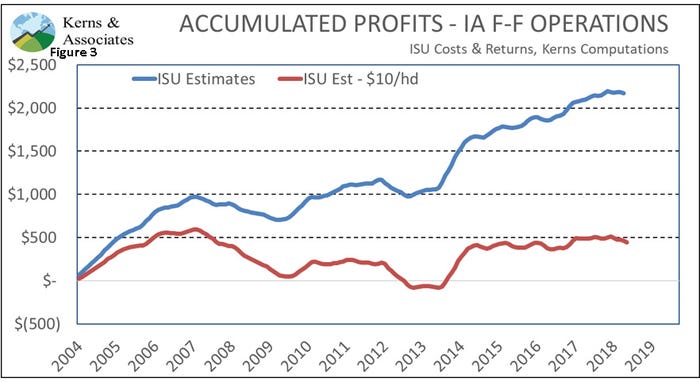

Figure 3 compares the accumulated profits of our modeled producer (top 20% or so) and the average producer ($10 per head higher costs) for January 2004 through December 2018. Probably no one has realized the top line in Figure 3 as the operation would have had to be in the top 20% every month. That means no health breaks in 15 years. There may be a few of those but not many.

Similarly, there are a lot of operations who probably didn’t see average profits for all of those months. Some may have seen significantly less from time to time and thus may be even worse off than the red line. The point is that there are pork producers in some tight financial straits already. Our outlook for 2019 is not rosy but it is not disastrous either, but still some operations may not make it through.

Prudent use of forward pricing mechanisms with a keen eye to your financial situation are paramount. Visit with your management and marketing advisers now to develop a plan to protect your business — and hopefully still allow opportunities to profit should things get better in the second half of 2019.

Source: Steve Meyer, who is solely responsible for the information provided, and wholly owns the information. Informa Business Media and all its subsidiaries are not responsible for any of the content contained in this information asset.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like