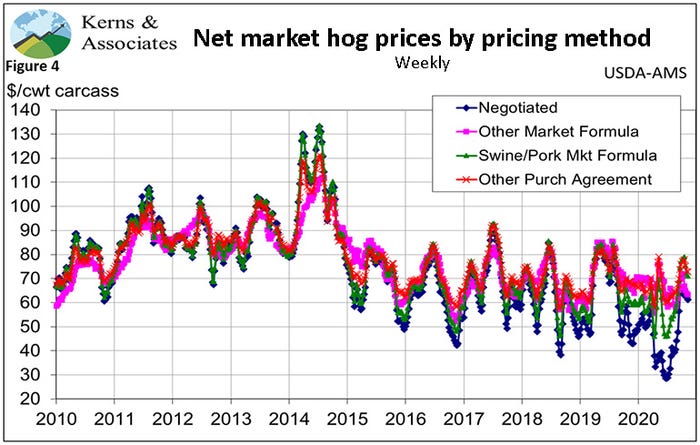

It's clear that those who sold only on the negotiated market or had their hogs tied to the negotiated market took a huge revenue hit over the past 18 months.

November 16, 2020

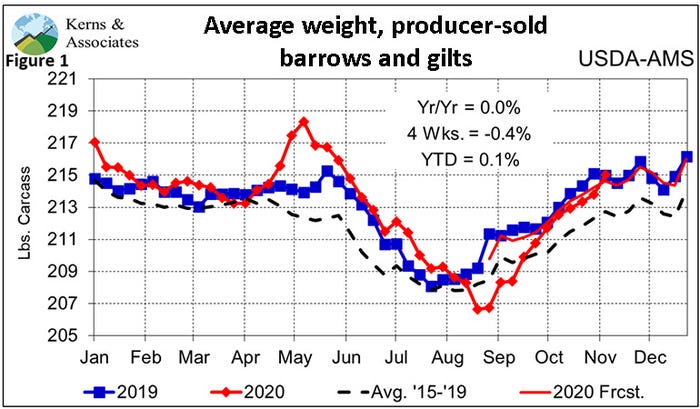

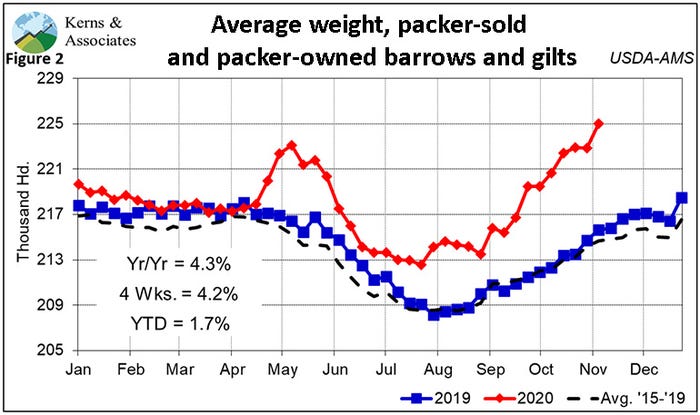

Producer marketings appear to finally be current but packer marketings are, if anything, getting further behind schedule. At least some packer marketings. The evidence of both factors appears in Figures 1 and 2.

The average weight of producer-sold hogs has been rising in a quite-normal seasonal pattern since early October. Last week's increase from 213.8 to 215.0 is a bit faster than normal but is no reason for "we're backing hogs up" alarms to go off anywhere. The 215-pound figure is equal to one year ago and weekly changes usually get choppy from here to the end of the year.

I think the reason is that by mid-November the impacts of cooler weather and fresh corn have become clear and there is no directional seasonal factor going forward. Since the big rebound of September, this chart looks quite familiar and everything we hear is that even those systems that were lagging in their marketings have now caught up.

Figure 2 is a whole 'nother story. This chart is the weighted average of the weights of packer-sold and packer-owned pigs. So it is a "packer-produced" average weight. Six "packers" (Smithfield, Seaboard, Prestage, JBS, Clemens and Tyson) rank among the top 15 producers in the latest annual ranking of the top U.S. pork-producing systems. Smithfield accounts for just over half of the sows held by those six packers so what happens with Smithfield-produced pigs has a major influence on Figure 2.

And last week's average "packer-raised" pig had a carcass that weighed a record 225 pounds, 2.2 pounds higher than the previous week and 9.3 pounds higher than last year. This hard evidence and a number of pieces of anecdotal evidence suggests that the situation in North Carolina continues to get worse. We still expect lower "normal" market-ready hog numbers to provide some room to get these heavies moved to harvest but continued challenges at Smithfield's Tarheel, N.C., and Gwaltney, Va., plants are apparently preventing much progress. And then last week Tarheel and Clinton, N.C., had wastewater challenges that limited operations. They can't buy a break.

This year's disruptions have once again shined a bright light on an issue that has been with us for a long, long while: Price determination and discovery. I list two aspects of one issue because I think they are both quite distinct.

Price determination is the interplay of supply and demand in the marketplace with the result being a market-clearing price. Price discovery, on the other hand, is the process of finding out just where supply and demand lie and where that market-clearing price may be. I view discovery as the actions of individuals where determination is the reflection of market forces.

Problems have developed as fewer and fewer economic agents representing a smaller and smaller share of the quantity supplied and demanded have engaged in the price discovery process. This decline leaves the agents' actions, I believe, potentially less correlated to the true supply-and-demand picture and, therefore, results in market prices that may not be representative of the true value of the product. Sometimes that price can be greater than "true value," but more often it results in a price that is less than "true value." This year has been the latter in spades.

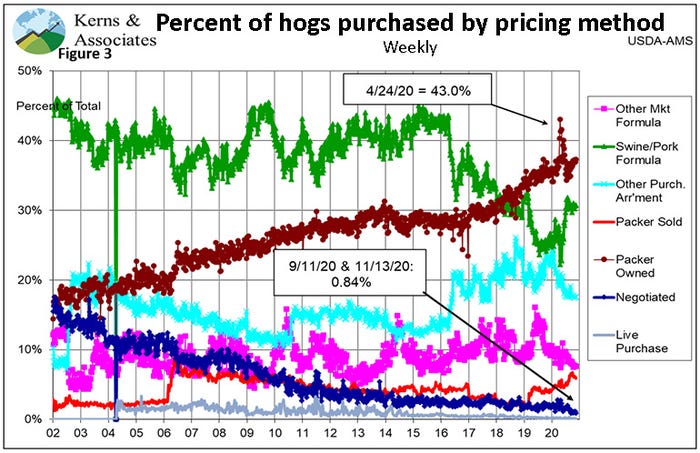

Last week saw yet another milestone as the percentage of hogs whose price was discovered through negotiations tied its all-time low of 0.84% of the total number of barrows and gilts reported under mandatory price reporting. Wednesday saw an all-time low of 1,655 head in the negotiated category — just 0.39% of that day's total. That does not mean that last week's average negotiated price of $62.10 was incorrect. In fact, that price appears to be one of the more "normal" prices we have seen for negotiated hogs in a while.

What these low negotiated shares tell us, though, is that a mismatch between the number of these "marginal" hogs available from producers and needed by packers is far more likely. Packers' needs are more and more fulfilled by hogs they either own or have contracted thus reducing their need for "extra" pigs. If the supply of those "extra" pigs happens to exceed their need — as they have frequently since mid-2019 and did by a wide margin when packing plants began closing and slowing operations rates due to COVID-19 cases — the value of these pigs falls sharply. When negotiated prices fall, they pull the value of the hogs sold on swine market formulas (roughly 60% of the Swine/Pork Market Formula category, I believe, or 15% of total barrows and gilts) down virtually dollar for dollar.

Figure 4 is pretty clear. Producers who a) tied the prices of their hogs to Lean Hog futures, b) sold hogs on another purchase arrangement due mainly to non-carcass merit premiums or c) had a substantial number of hogs prices on the cutout value (and thus drove the difference between Swine/Pork Market Formula prices and Negotiated prices) did OK pricewise in 2019 and even 2020.

That doesn't mean they always will. Tying to futures can be a gain or a loss. It usually stabilizes prices over time, but it is not always a winner. Earning OPM premiums for antibiotic free or racto-free (when those were paid) or pen gestation involves extra costs or lower productivity. Cutout value pricing is highly dependent on the specific terms.

But it is clear that those who either sold on only the negotiated market or had their hogs tied lock-step to the negotiated market took a huge revenue hit over the past 18 months or so. It appears that many of those who are exiting the business this year were in this group.

Would anyone like to try to convince producers that they ought to be negotiating the prices of more of their hogs against this backdrop?

None of this is meant in any way to suggest that producers whose hogs were based on the negotiated market were silly or stupid or anything of the sort. For many years, there were enough highs in the negotiated market to offset the lows and careful analyses of those historical data showed that, depending on the alternative being offered, basing hog prices off the western Corn Belt or Iowa-southern Minnesota negotiated price was a reasonable decision. In addition, the mechanism was about as transparent as one could get in the absence of open outcry auctions.

But the possibility of a mismatch between the marginal supply and marginal demand for hogs and its severe consequences is not new. It has been talked about for at least 22 years since the price debacle of 1998. So, the risk of such was most likely calculated. Or certainly should have been.

The issue to me is whether individual producers were given a choice. Maybe all were at some point. I don't know if that is true or not. But if it is not, what would be a reasonable criterion to separate the offered from the not offered? Transaction costs per unit have always been the obvious divider for such things but in a computerized world where billing and checks and records are completely automated, do transactions costs differ that much across suppliers?

An effective and fair way to determine the value of a pig being sold to a packer is a must if this industry is to move forward without complete integration. I know producers don't want to be "integrated" by packers and I don't believe that packers really want to raise that many hogs.

So the challenge is clear: How can we price hogs in a fashion where one party is not taking advantage of the other and where the combined values are large enough for both to earn at least normal returns on invested capital? It's best we start hashing the answer out soon.

Source: Steve Meyer, who is solely responsible for the information provided, and wholly owns the information. Informa Business Media and all its subsidiaries are not responsible for any of the content contained in this information asset. The opinions of this writer are not necessarily those of Farm Progress/Informa.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like