Sharp increase in cutout values corresponds with shortage of pork production and higher prices resulting from plant closures and processing restrictions.

There has been a lot of attention recently on the CME Lean Hog futures contract and its effectiveness as a hedge for producers. Given deeply negative producer margins and significant hog price volatility over the past several weeks, there is understandable concern about how closely the futures market and cash market are moving together, and the impact this may have on producer hedges in their risk management activities.

A lot has already been written on this topic, including in this space, and my purpose here is to hopefully add some clarity on why this has become an issue for some but not necessarily all producers who use the board to hedge their risk exposure. It is an important topic for the industry and one that must be addressed as the futures market provides the essential functions of price discovery and risk transfer. It is in the best interest of both the CME Group and the pork industry to assure that the futures market provides these two critical economic functions and serves the interests of the greatest number of market participants.

U.S. hog futures began in 1966, following the launch of pork bellies in 1961 which was the first livestock contract listed by the CME and a huge success for the exchange. In fact, the CME is often called "the exchange that pork bellies built," in reference to how the livestock futures complex reinvigorated the moribund CME during that decade. Ironically, the pork belly contract has since been delisted by the exchange while the hog contract has continued to grow and evolve over time in response to changing dynamics in the U.S. domestic swine industry.

Originally listed as a "live" contract, hog futures specifications stipulated a physical delivery settlement procedure, with a 30,000-pound trading unit and deliverable grade of USDA No. 1, 2 and 3 barrows and gilts. In 1997, the contract was updated to a "lean" basis, or carcass as opposed to live animal weight. The trading unit was also revised to 40,000 pounds, reflecting the increasing size of animals being harvested in the cash market.

Another change concerned the settlement procedure, in which a financial settlement replaced the physical delivery mechanism in 2003. An index of cash hog prices now determines the final settlement price of CME lean hog futures at expiration. The calculation of the index is a weighted average of the daily price and volume for negotiated, swine or pork market formula, and producer-sold negotiated formula transactions as reported on the National Daily Direct Hog Prior Day Report-Slaughtered Swine report released by the USDA.

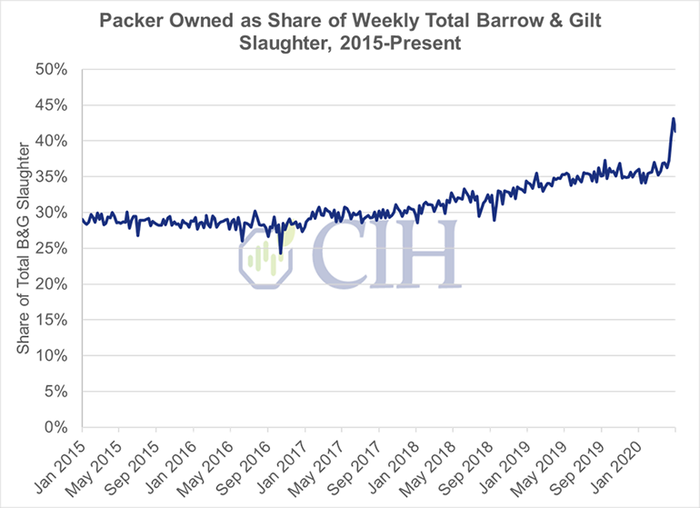

Just as the hog futures contract has evolved over time, so too has the price discovery in the cash hog market and complexity of supply agreements. An ongoing trend in vertical integration of the pork industry has resulted in increasing numbers of hog producers becoming more closely aligned with processors, and in some cases, becoming processors themselves. This has shifted their risk profile as they incorporate exposure further downstream in the supply chain. Additionally, independent hog producers are increasingly tying part or all their forward contracts to the pork cutout in an effort to diversify their price risk (see Figure 1).

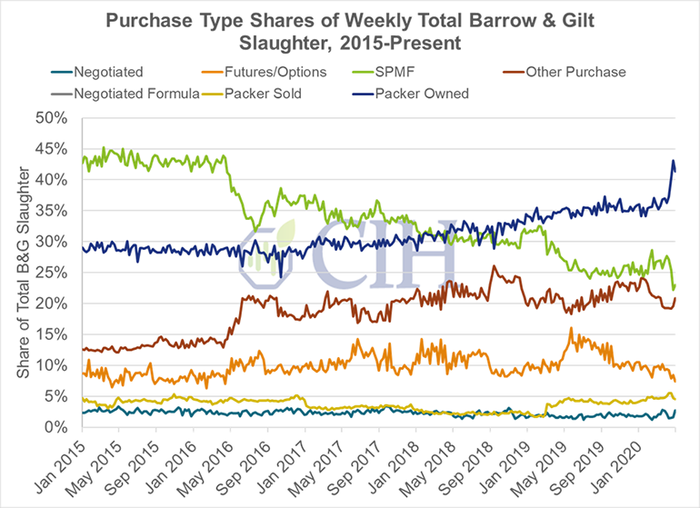

As a result, an increasing number of hogs under the swine and pork market formula purchase type are using formulas that reference pork cutout value in their base price calculations (see Figure 2). At the same time, cash hog volumes negotiated directly between buyers and sellers in the spot market has slowly diminished and now represents only about 3% of total barrow and gilt slaughter.

The relationship between cash prices and futures prices, or basis, has experienced significant deviations recently depending on the formulas used in base price calculations negotiated between buyers and sellers. Because the CME Lean Hog Index is calculated from a weighted average of the daily price and volume for producer-sold negotiated, swine or pork market formula, and negotiated formula transactions, the composition of this weighting and these averages is necessarily a function of how these transactions are distributed in cash hog price discovery. Given the increasing trend of producer-owned hogs using formulas referencing cutout that these animals are tied to, the pork cutout now exerts greater influence on the CME Lean Hog Index (and hog futures by extension) than was the case historically. It is now estimated that approximately 35% of the index is based off the pork cutout, with the remainder tied to the swine market.

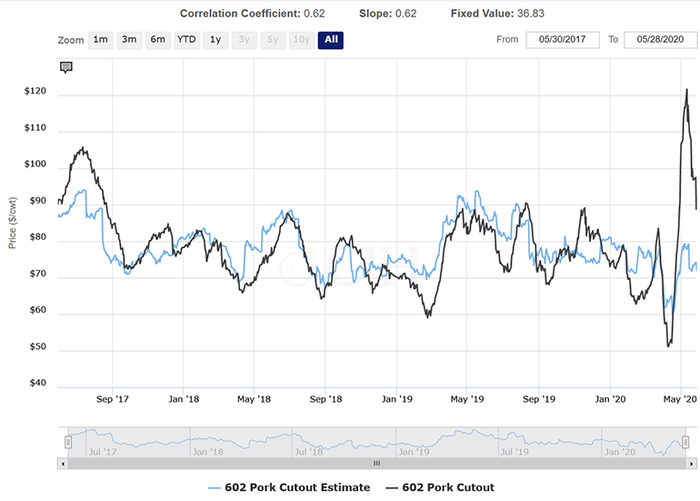

For those producers who are discovering their cash market hog value as an exclusive function of either the pork cutout or the swine market, this has become an issue as the correlation between CME Lean Hog futures and pork cutout has broken down in the past few years (Figure 3). Conversely, for those producers whose base price formulas more closely mimic the composition or weighting of the CME Lean Hog Index, this is less of an issue as the futures market will correlate better to their cash hog price discovery.

While there are many contracts negotiated this way, many others are not, which is a growing concern for the industry. What has really shed a light on this issue now is the stark divergence between the value of cash hogs and pork prices. The sharp increase in cutout values recently corresponds with the shortage of pork production and higher prices that have resulted from plant closures and processing restrictions. This development has simultaneously rendered cash hog prices worthless in some cases, with producers having to pay to euthanize hogs and dispose of carcasses. This creates a bifurcated cash market of haves and have-nots, with those whose contracts are tied exclusively to the swine market faring the worst, and those with contracts exclusively based off cutout faring the best.

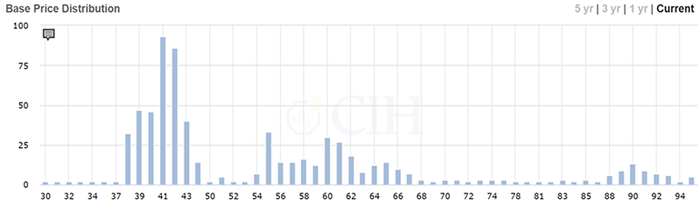

Figure 4 shows a distribution of this reality from data in the Swine Contract Library maintained by the USDA's Grain Inspection, Packers and Stockyards Administration. The histogram models the current base prices received by producers in the x-axis while the y-axis represents the number of contracts resulting in that base price. There are a few things that stand out in this chart. The first is the wide distribution of prices currently being received by producers delivering hogs, anywhere between $30 per hundredweight to $95 per hundredweight. The second are the three clusters of data that show up in the distribution. The first cluster on the far left represents contracts whose base price formulas are determined as a function of the swine market (e.g., Iowa-southern Minnesota, Western Corn Belt, Eastern Corn Belt). These contracts are currently receiving base prices somewhere in the high $30 per hundredweight to mid-$40 per hundredweight range. The middle cluster corresponds to contracts whose base price formulas are derived from a blend of both the swine market and pork cutout. The prices received for these contracts range from the mid-$50 per hundredweight to mid-$60 per hundredweight currently.

These types of contracts more closely resemble how the CME Lean Hog Index is calculated and are therefore closest to the current value of the index. The cluster on the far right represents contracts whose base price formulas are a function of pork cutout, and these contracts are currently receiving prices from the high-$80 per hundredweight to low-$90 per hundredweight range.

For producers in the middle cluster, the CME Lean Hog futures contract is likely working well in that the prices being received in the cash market are closely tied to the index that the contract settles to. For those producers, however, in the far left or right clusters, the severe deviations between the cash prices received and the value of the futures market presents a challenge to their hedging activities. For those whose contracts are exclusively a function of the swine market, they are experiencing extremely negative basis values as their cash price is being discovered at large discounts to the futures market. At the other extreme, while those producers priced exclusively off pork cutout are enjoying the opposite scenario with large premiums to the futures market and a positive basis, initiating new hedge positions is not very compelling and quite risky with futures depressed relative to their cash price discovery.

The issue at hand is not necessarily that the hog futures market is broken as much as due to the complexity of the prices producers receive through supply agreements, there is no longer a one-size-fits-all hedging instrument. As illustrated above, because producers have varying degrees of exposures to both the swine and cutout markets, having a second mechanism to hedge each of these exposures and tailor them to individual producers will be more effective. The CME has created a pork cutout index that could be a precursor to a pork cutout contract complimentary to existing lean hog futures. The existing lean hog contract specifications may continue to serve the hedging needs of many market participants, while the addition of a pork cutout contract might better match the cash price discovery of other hedgers. This includes many on the buy side as well as packers, allowing for price discovery further downstream in the supply chain and potentially creating spread opportunities to protect processing margins. Listing pork cutout futures and options side-by-side with existing lean hog futures and options would be welcomed by the industry and allow more market participants to better align their unique risk profiles to hedging strategies.

Source: Chip Whalen, who is solely responsible for the information provided, and wholly owns the information. Informa Business Media and all its subsidiaries are not responsible for any of the content contained in this information asset. The opinions of this writer are not necessarily those of Farm Progress/Informa.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like