The fly in the ointment is that expansion is still progressing rapidly. Breeding herd growth of 1.5% to 2.0% is easily in the cards. Litter size growth has slowed a bit, but is still between 1.0% and 1.5%.

May 1, 2017

My colleague, Dennis Smith, boldly brought up the “C” word (competition) last week in his review of the current conditions in the hog market. We don’t talk much about competition anymore it seems and there are some good reasons.

First, there hasn’t been much research and certainly no legal cases that have found competition for hogs lacking over the past few decades. I wonder about that sometimes, but I also know how both the economic and legal analyses are done on the competition question and can see that there has been little or no evidence of reduced competition. Some might say that we just haven’t been looking hard enough. The truth is that, short of overt collusion or some other smoking gun, it is difficult to prove illegal action to reduce prices. And, thank goodness, we are all at least theoretically innocent until proven guilty so I for one am glad the bar is set reasonably high for any crime, anticompetitive behavior included.

Second, though the pork packing sector — like seemingly every sector except, perhaps, alcoholic beverages — has become more and more consolidated over the past 30 years, packers have bid aggressively for hogs when hogs have been scarce and when pork cuts have been valuable. Would the December through February $80 rally in belly prices (about $12.80 per hundredweight on the cutout) have produced a $10 per hundredweight rally in the cutout and a $21 per hundredweight rally for negotiated hog prices without some degree of price transmission efficiency? I hold my packer friends in high regard but they hardly ever (if ever!) bid for hogs out of any sense of altruism. Producers’ profit challenges have just as frequently come from the cost side as from the hog price side in recent years. Everybody made money when consumer demand was strong. All of those sound like characteristics of a pretty competitive marketplace.

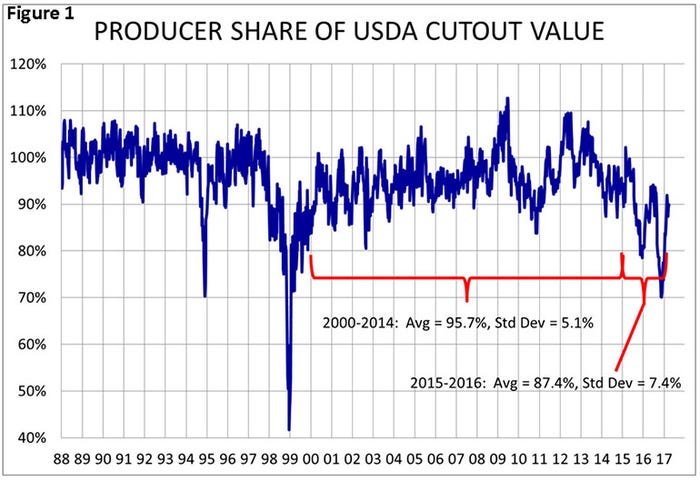

The most valid indictment of the hog-pork pricing system over the past couple of years is the lower share of the cutout value that is finding its way to producers’ pockets. I recently included the chart in Figure 1 in a presentation I made to a room full of producers and packers. The line simply represents the national average net hog price across all pricing methods divided by USDA’s estimated cutout value. Some lively discussion ensued — primarily from producers since packers will never (and should never for antitrust reasons!) discuss this topic among themselves either publicly or privately. A few things jump out from the chart.

• The percentage has indeed been lower the past two years. From 2000-14, the national average hog prices averaged 95.7% of the cutout value with a deviation of 5.1%. That means, assuming the share is distributed normally, we would expect the producer to be between 85.2% and 105.9% about 99% of the time. During 2015 and 2016, producers’ share averaged just 87.4% with a 7.4% standard deviation. That puts the 99% confidence interval at 72.6% to 102.1%.

• The four most significant down spikes all correspond to periods of high packing capacity utilization. The 1994 spike came on the heels of 20 years of packing plant closures across the United States, and marked the first time in my career we had bumped into capacity — and thus was the beginning of my capacity tracking effort that continues today. The 1998 spike was, of course, a watershed in the history of the U.S. pork industry. The dip to less than 80% in 2015 corresponds to three weeks right at capacity that fall. That episode had been prevented the prior two years by extremely high 2012-13 feed costs and porcine epidemic diarrhea virus in 2013-14, respectively. Finally, the spike down last fall corresponds to a capacity crunch as severe as that of 1998. It is my belief that packers did not push prices nearly as low as they could have. They remember the political and public relations fallout of the 1998 episode.

• The producer share has barely rebounded to the bottom of the 2000-14 range so far in 2017. A big reason is that hogs are still plentiful. The industry isn’t seeing near the 2.5 million per week of last fall but 2.3 million is easily the highest level — and consistently so — ever for this time of year. We expect weekly totals to remain well above 2.1 million in non-holiday weeks all summer and then to peak out nearly 2.6 million in a few weeks this fall. Hog supplies will not push producer shares higher.

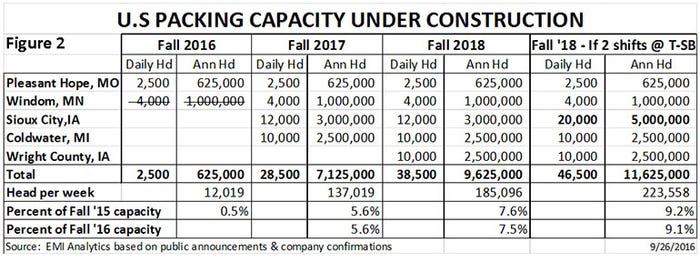

• The factor that is now changing is capacity. See Figure 2. Prime Pork in Windom, Minn., (4,000 head per day) opened last week. Seaboard-Triumph in Sioux City, Iowa, (12,000 head per day) has announced that they will open in late-July. Clemmons Food Group in Coldwater, Mich. (10,000 head per day) is still looking at an early September opening for commercial operations. Seaboard-Triumph plans to add a second shift (10,000 head per day) in July 2018 while Prestage Foods’ Wright County, Iowa, plant is under construction with plans to open in late-2018. Add all those up and you get nearly 10% more capacity per week than was available just last fall.

So will these extra plants swing the leverage so producers will enjoy shares of the cutout value in the mid-90s or more? I think it may for short periods of time but I suspect the level to return to the general 90 to 100 percent range of the pre-2015 period. At least for a while.

The fly in the ointment, though, is that expansion is still progressing rapidly. Breeding herd growth of 1.5% to 2.0% is easily in the cards. Litter size growth has slowed a bit, but is still between 1.0% and 1.5%. Weights have been flat for a number of reasons but cheap feed will encourage additional finishing space to put some of those still-profitable pounds back on hogs later this year and into 2018. I expect capacity utilization rates to be high again by late-2018. The Prestage plant will bring some respite in 2019 and, maybe, 2020 when more hogs will again swing the pendulum back in the favor of packers.

Which brings us to the ultimate question: Can demand for U.S. pork grow enough to keep everyone profitable? Let’s hope so.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like