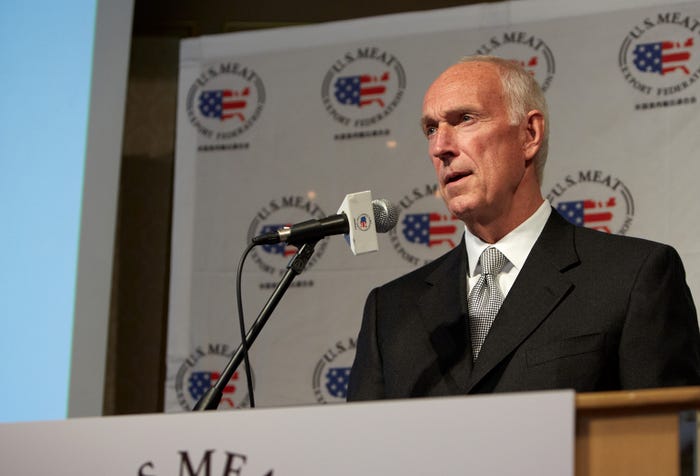

Philip Seng says the U.S. pork industry and its partners like the USMEF need to understand the minds of the global consumers and how the retailer can shape the minds of the consumer.

May 26, 2017

Pork Master Philip Seng’s contribution to the international meat trade scene echoes around the globe. An Iowa farm boy fluent in Japanese, with Olympian discipline deep-seated in mental strategy, is an unspoken formula for success.

Yet his gentle, but strategic way of guiding the most vertically integrated trade association in the meat and livestock industry is the underlying reason the U.S. Meat Export Federation has made large strides in increasing the value of U.S. meat exports.

If you ask Seng about his career path, he will not mention the long list of awards or milestone leadership opportunities, but his resume speaks volumes. He was a member of the inaugural class of the Meat Industry Hall of Fame in 2009 and recognized by National Provisioner as one of 25 industry icons who has made a significant impact since 1991 in conjunction with its 125th anniversary. Seng also has served as the only American ever to be president of the International Meat Secretariat and on the President’s Agricultural Policy Advisory Council in Washington. Interestingly, his marketing strategies and approach to the Japanese market serve as a case study in the Harvard University Business School, where he has been a guest lecturer on several occasions.

As a child, Seng was not a stranger to working, growing up on a typical Iowa farm raising corn, cattle, pork and beans. On the other hand, his appetite for international flavor — in particular, Asian culture — took his mind, heart and eventually him far from the farm. “I received a bachelor of science in political science with a heavy history background and my master’s in East Asian studies. So that tells you a little a bit about my focus,” says Seng.

Since China was a tightly closed market in the 1970s, Seng spent time in the market and economy of the future — Japan — after graduate work. He was trained in judo for the U.S. Olympic team and also worked in the Japanese foreign ministries, in journalism and taught at a Japanese university. Living and working in the Japanese culture granted Seng a unique exposure and understanding of how their government works.

Seng returned to the states after it was clear there would be no Olympics for U.S. athletes in 1980 as result of a U.S. boycott of Russia invading Afghanistan. At this moment, he became serious about his career and began working for a Japanese company in the United States, working in total quality marketing and management.

He returned to Japan in 1982 upon accepting a job as Asian director for the U.S. Meat Export Federation. This was a pivotal period for agricultural trade relations between the United States and Japan through a series of agreements on beef and citrus.

At the same time, it was the era for establishing the historical groundwork for U.S. pork exports in Japan. Seng and the USMEF team worked diligently in soliciting U.S. pork processors to open offices in the country. “I always maintained in order to be a factor in the market you have to be in the market,” he explains.

Active participation in the market has always been a guiding principle for Seng, no matter which job title he held, from Asian director to vice president of international programs to the chief executive officer today. Living, working, walking and breathing in the actual country you do business with is essential to marketing the right product.

On his first day on the job, USMEF had three offices internationally, and today there are 18 international offices with consultants around the world. “We exported last year close to $6.5 billion worth of pork. We have grown from a very small amount to a large amount in just 35 years’ time,” notes Seng.

Most of the pork marketed globally is sold as raw material for further processing. One major turning point in the 1980s for the U.S. pork industry was selling chilled pork to Japan, explains Seng. USMEF worked with Iowa State University, Texas A&M University and packers to develop chilled pork to go to Japan. The first shipment of chilled pork was sent to a Japanese supermarket chain in 1987. “That helps us diversify in the market because until then we were only subject to a small portion of the market that is raw material for further processing,” notes Seng.

A fortunate chain of events accelerated U.S. pork into Japan in a big way. In the 1990s, Taiwan was supplying Japan with its chilled pork. However, an outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease halted the supply at the same time the United States shipped its first load. “It was a combination of working to get chilled pork accepted in Japan, and the No. 1 supplier was ineligible. We were able to take up that role,” states Seng. The Japanese are meticulous. The specification in cutting, color and quality became a factor. The United States was able to meet those specifications, launching the U.S. into the retail market. This diversified the export portfolio for the U.S., allowing growth of the market footprint substantially.

“I would say this was one of the biggest catalysts for change with the advent of chilled pork internationally,” says Seng. “It allows us to go after the retail trade, go direct to consumers. That is why we see more consumer activities in Japan, Korea and to some degree in Mexico because we can sell chilled pork and reach the consumer through that process.”

Beating the competition

The mission of the USMEF is to link the packers with the first customer and promote quality meat. Its goal is to find what product is suitable for the target market, what it needs to do to promote those products and how to do it on a consistent basis.

Once that is solidified, the USMEF team works down the channel in the marketplace. In all the markets, the goal is to take a foreign meat product into an international space and make it as familiar to the consumer as a domestic product. This is accomplished through educational and promotional events, demonstrating how to maximize the product.

Competition in the international market space is aggressive. Every leading pork-producing country wants to sell its pork worldwide. Frankly, Seng says, in his early years the competition for U.S. pork was not as tough as it is today. Still, the support from the government by providing office space in foreign markets helped the U.S. gain a competitive advantage. “We were able to set the table, and the competition came in to try to displace us,” notes Seng.

The fact that the U.S. is a net exporter of pork today was not by accident. Seng says it goes back to the old Chinese adage: “One generation plants the tree, the next generation gets the shade.” The groundwork for today’s global meat trade was set in the 1980s.

The growth in U.S. meat trade is not just a result of crafty free-trade agreements. In fact, Seng says there is no market access agreement for roughly 50% of the U.S. pork presently exported internationally. While the USMEF’s single mission is to link the quality meat products of the packers with the global customer, the strategy in each global market is different. In each market, the USMEF identifies the barriers and devises a way to get around those impediments.

Seng tells the tale of the two largest pork markets — Japan and Mexico — to illustrate how the road to market access is unique for each country. For Mexico, the USMEF participation in the North American Free Trade Agreement negotiation resulted in eliminating the 20% tariff over 10 years. Immediately, this obviously allowed the U.S. to become more competitive over South America and Europe, making Mexico the United States’ largest export market by volume.

On the other hand, Japan instituted its current import system with border protection and tariffs in 1971. Despite the barriers, the United States has grown the amount of meat exports significantly. For U.S. pork, Japan is the largest value market.

“I am just proud of what we were able to accomplish in NAFTA as I am with Japan. One is a market we had good access to as result of NAFTA, and the other we haven’t had access or major changes since 1971,” Seng states.

Trade agreements are not a guarantee for success in a marketplace. Trade negotiations need to be dignified by solid marketing plans, explains Seng. The competition may also have equal or more favorable access through trade negotiations.

There are two forms of competition in the global meat trade scene — the commercial and the trade access competition.

“The playing field is not as level as it used to be because of all the proliferation of these different kinds of free-trade agreements, economic partnership and regional trade agreements. It is a changing world,” concludes Seng.

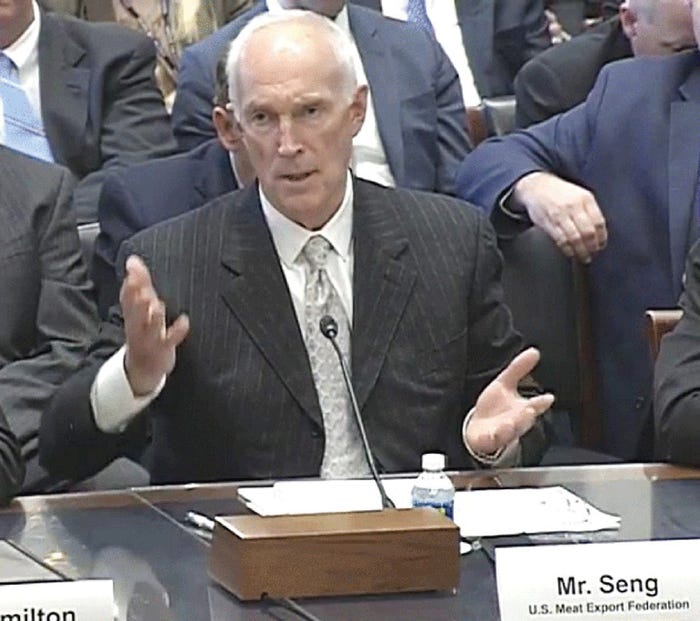

Philip Seng says the U.S. pork industry has to defend the science behind the production.

What’s ahead?

The world is an opportunity. To dominate the global pork market over the next 10 years, it will take seamless cooperation.

“The future is determined by what we make it. Over the course of the years, the U.S. pork industry made some great decisions,” states Seng. “I have always said how well we work together will determine how successful we will be in the future.”

Globalization is under question right now, but globalization has always been positive for meat consumption in general. As long as the U.S. pork producers are committed to continuing to produce quality, safe pork products, then the growth is unlimited with more than 95% of the world’s population outside of the United States. “What we need to do is find these new opportunities, which are sometimes these smaller niches. There is not a lot of Japan and Mexico out there,” Seng says.

In the past, the USMEF plan was to develop the market in these foreign marketplaces. Nevertheless, the future is about keeping up with the competition. For some global markets, the approach is about displacing the competition, which takes more resources.

Prosperous global meat trade comes down to the three D’s: development, displacement and defend.

“We have to defend our philosophies of production. We have to defend the role of science in meat production both from the production and processing side,” Seng firmly states. “There are so many things that our competition is using to try to displace and discourage us that we have to be vigilant, resourceful and adaptable to these changing markets.”

Challenging leadership

The USMEF is comprised of 103 employees, with 70% located in international offices, speaking 25 different languages and knowledgeable on multiple cultures. The contrasting nature of the global meat trading game matches the eclectic group Seng assembled to promote U.S. meat. “We believe diversity is our strength,” he notes.

As the leader, Seng looks for critical thinkers who can probe for the truth in the marketplace. He understands remaining flexible, but being tactical is quintessential. There is not one playbook that works across all the international markets. It is about putting the best people with the best comprehension of the culture to guide the effort and formulate the best action for each country.

“You have to take a look at what each market presents. It is like reading a different defense,” says Seng. “There is not one plan for the world. Each market gives us something. We try to make it and shape it to advance our industry.”

Operating with integrity and seeking the truth in the market are two driving factors for Seng personally. Running an organization with high standards with a staff deeply committed to the cause is very important.

“As an American traveling around the world, I take great pride is representing U.S. agriculture, our producers and meat industry internationally,” says Seng. “I am very proud and humble to be in a position to meet such great people. It is so wonderful to have such an international network of friends.”

Word to U.S. pork producers

Together, the U.S. pork industry and its partners like the USMEF need to understand the minds of the global consumers and how the retailer can shape the minds of the consumer, says Seng. “I have not lost a lot of sleep on the way we produce our pork. My main concern is how we can sell the pork we produce. Where is the opportunity?”

The USMEF leaves the business of raising pork to America’s pig farmers. The U.S. swine industry is committed to the science behind raising pork.

“United States always has been a strong advocate of sound science. Having a position of sound science is important, but we have to have an acceptance of the science internationally. The industry and the people involved in these new technologies need to do more to have our science accepted,” Seng stresses. “We need to a better job than we have done in illustrating why science is so integral to our production in the United States. It is a challenge of the future.”

After checking the list of individuals on the Master of Pork Industry list, Seng is humbled with the award. “I am honored and very touched to receive the recognition. When I receive an award, it is not just about me, but the work of the team to advance pork internationally. Sometimes I feel so much we do is overseas, and it is not noticed. It is a nice testimonial to our hard work.”

You May Also Like