thumbnail

Livestock Management

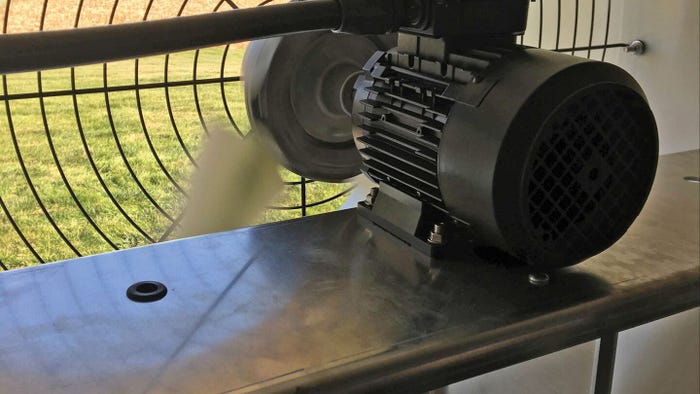

Protect piglet health during warm weather transitionProtect piglet health during warm weather transition

Get fans, shutters and other cooling system components ready for hotter temperatures.

Subscribe to Our Newsletters

National Hog Farmer is the source for hog production, management and market news

.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)