Hog Reproduction

thumbnail

Livestock Management

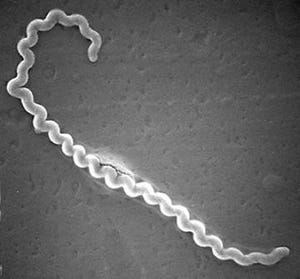

Sperm per dose: How low can we go?Sperm per dose: How low can we go?

Does lowering semen concentration impact sow performance?

Subscribe to Our Newsletters

National Hog Farmer is the source for hog production, management and market news

.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)