thumbnail

Farming Business ManagementPork production software aids in difficult decision makingPork production software aids in difficult decision making

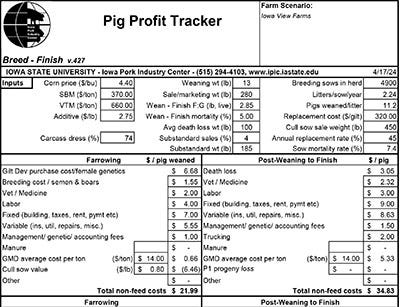

Pig Profit Tracker can help producers assess value, performance changes within their operation.

Subscribe to Our Newsletters

National Hog Farmer is the source for hog production, management and market news

.jpg?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)