As fast as the virus spread across the world’s largest pork-producing country, the U.S. pork industry has worked twice as fast over the last 365 days to prevent and prepare for a potential outbreak.

It’s now been over a year since China’s Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs confirmed its first African swine fever outbreak in Liaoning province. Twelve months later the country has had over 140 outbreaks in 32 provinces and regions and more than 1.16 million pigs have been culled in an effort to stop the spread of the disease in the Far East.

As fast as the virus spread across the world’s largest pork-producing country, the U.S. pork industry has worked twice as fast over the last 365 days to prevent and prepare for a potential outbreak on American soil. The National Pork Board, the National Pork Producers Council, the American Association of Swine Veterinarians, the Swine Health Information Center, the North American Meat Institute, the U.S. Meat Export Federation and the American Feed Industry Association have joined forces and to date, the coalition has completed more than 35 action items involving research, education, prevention and preparedness.

“I can't tell you in the last year how many producers and people outside the industry have asked me about the ASF situation in China,” says Liz Wagstrom, chief veterinarian of the National Pork Producers Council. “This provides an opportunity for us as an industry to promote our Secure Pork Supply program and biosecurity at pig shows. The U.S. pork industry wants to remain vigilant to prevent ASF from entering our borders or ports.”

Paul Sundberg, Swine Health Information Center executive director, says he’s also seen an impetus to collaborate more with government officials over the past year.

“In the last year, in my experience, there has been more cooperation and collaboration with the USDA about ASF that we have had in any other programs, maybe short of the pseudorabies eradication program back in the 1980s and 1990s,” Sundberg says. “That was an extraordinary amount of collaboration that would happen over a period of years. The collaboration and activity, all that both the industry and the USDA have done over the last year, is really an impressive amount and something that I think has absolutely helped in our prevention, preparedness and ability to respond. We don't know that we can guarantee we're going to keep it out, but we are way better than we were in August of last year.”

After reflecting on this past year with Wagstrom, Sundberg and several other pork executives, eight key action items stood out that the U.S. pork industry has implemented thus far since ASF broke in China, forever changing the way the industry will respond to and prevent any emerging or foreign animal disease from entering the U.S. swine herd.

Research

In just one short year, U.S. researchers have completed studies on feed/dust sampling methods and protocols, the validation of the extraction process for the detection of virus in feed and feed ingredients, feed additive mitigation, oral infectious doses in both liquids and feeds, disinfectants, epidemiology and diagnostics work as well as made proposals for further ASF-feed testing, diagnostics and vaccine.

While the science on viral transmission through feed and feedstuffs is still relatively young, it has yielded some useful information on mitigating the spread of costly viruses, such as ASF. One study has shown the theoretical ability for pathogenic swine viruses to survive transport to the United States in imported feedstuffs. Another one has shown the ability for ASF to infect pigs via feed and normal feeding activities.

Wagstrom says that amount of industry research the U.S. has completed in such a short amount of time is extensive compared to other countries.

“Using Pork Checkoff funds, the Swine Health Information Center and the National Pork Board have financed a tremendous amount of very practical research – including issues such as disinfecting, risks from animal feed, looking at mitigations in animal feeds, looking at feed holding times and more,” Wagstrom says. “I don't know of other countries that are doing that level of research.”

Diagnostics

For Sundberg, one of the most foundational action items that has happened since August of last year, has been improved diagnostics. Prior to the ASF concerns in China, the only tissue that was approved by the USDA to test in any investigation was whole blood.

“There was nothing else as no other tissues were approved as an official ASF test, and diagnostically there just aren't samples of whole blood that come into the diagnostic lab as part of routine submission. They just don't do that,” Sundberg says. “That's a real problem with being able to find it quickly and that has expanded at a rate, that in my experience, was unprecedented with the cooperation of the USDA.”

The industry not only worked with the USDA, but also the National Animal Health Laboratory Network and National Veterinary Services Laboratories to promote the inclusion of a variety of tissues for submission for the diagnosis of ASF. Now in addition to whole blood, diagnostic labs are also permitted to do official ASF tests on spleen, tonsil and lymph node tissue samples.

“Prior to those efforts, whole blood was the only validated sample type that you could submit and get a positive diagnosis for African swine fever,” says Harry Snelson, DVM, American Association of Swine Veterinarians executive director. “Since then we've worked with USDA and the other groups to promote other tissues such as spleen, lymph nodes and those types of things to give veterinarians in the field a wider variety of tissue types that they might submit. The challenge is to try to focus those ASF diagnostic efforts on tissues that are more typically submitted during a normal diagnostic workup. Being able to detect, as early as possible, the introduction of a foreign animal disease is critically important.”

While spleen and lymph nodes submitted to diagnostic labs are two tissues that are routinely submitted, Sundberg says liver and lung tissue samples for example could also be further considerations as they are currently accepted in diagnostic laboratories in the European Union.

“Anything that we can do to broaden that list of tissues that are accepted officially would be important,” Sundberg says.

Surveillance

In addition to spleen, lymph nodes and tonsils being included in the official ASF testing, the tissue samples can also be tested for ASF, even if they were submitted as part of a routine submission under the USDA’s new ASF surveillance plan. The surveillance efforts conducted by the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service now tests samples from high-risk animals, including sick pig submissions to veterinary diagnostic laboratories; sick or dead pigs at slaughter; and pigs from herds that are at greater risk for disease through such factors as exposure to feral swine or garbage feeding.

According to Snelson, the USDA had a surveillance program in place for classical swine fever for several years, but the one developed for ASF and foot-and-mouth disease had never actually been implemented.

“As African swine fever began to spread, we encouraged USDA to pull that off the shelf and make that a functional active program, which they have recently done,” Snelson says. “That has answered another spoke in that prevention and recognition wheel that we're all trying to address.”

As Sundberg points out, the surveillance program ensures suspicious samples are being tested, regardless if a veterinarian suspected a FAD threat.

“So if I am out in practice, I see what I think is a hot PRRS (porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome) or septicemic salmonella, which absolutely looks like ASF, I submit those samples to the diagnostic lab thinking, 'OK, I'm going to get salmonella back out of these,'” Sundberg says. “The diagnostic lab looks at the case history and looks at the samples there and says 'this case is compatible with ASF. We'd better test it' and they have the ability to test it without doing a foreign animal disease investigation. That's a huge step forward in our ability to detect the first infections and therefore quickly respond to them.”

Sundberg foresees the next step in surveillance being the validation of oral fluids.

“To be able to monitor and surveil for ASF protection is a cornerstone to our ability to respond to the virus,” Sundberg says. “That's part of what we need to do for preparation because that ability to use oral fluids to be able to monitor and do monitoring and surveillance for ASF is critical to our ability to respond.”

Border patrol

Wagstrom says the industry has been doing an exceptional job working with government to address diagnostics and surveillance issues, including U.S. Customs and Border Protection. The USDA has promised 60 new dog teams to be added to the CPB team to help sniff out any illegally imported products at ports of entry. More legislation is in the works to authorize hiring additional agricultural specialists and canine teams each year. The CBP has also been in open communication with the industry about reviewing penalties and fines, revising questions on declaration forms and receiving feedback on inspection performance.

“We have an agreement with CBP, If we hear somebody who came through our ports of entry and felt their inspection was not what it should have been, we will let the CBP know and they will use that as a training opportunity for further inspectors,” Wagstrom says. “I think our concerns and aggressiveness has helped the agency make sure they remain vigilant on ASF prevention.”

The CBP’s heightened awareness and the extra beagles on staff have been a progressive step forward, Sundberg says.

“The work that we've done with Customs and Border Protection I think is unprecedented. Having that much interaction with them and their response and willingness to work with us, that's been very good to have that communication back and is a big step forward,” Sundberg says.

Collaboration

While he doesn’t see the role of veterinarians changing much in pork production as traditionally practitioners have been very involved in preventing emerging and foreign animal diseases from entering the herd, Snelson has seen both AASV as an association and individual veterinary members becoming much more active in state and regional response plans.

“We have been very active in collaborative processes with producer groups such as the National Pork Board, National Pork Producers Council and Swine Health Information Center to try to focus efforts on working with both state and federal animal health officials, as well as researchers to try to focus some of their attention and their efforts on making sure that they have addressed concerns for African swine fever,” Snelson says.

According to Wagstrom, most of the tabletop response exercises in the past have focused on FMD. The USDA's APHIS Veterinary Services National Training and Exercise Program exercises, which will conclude in September with the 14 largest pork-producing states, has been key in answering questions about pig movement and regional plans. Over the past year, several states have also opted to have smaller, regional discussions or exercises. For example, Oklahoma has completed two, four-state exercises.

“That's really important because of how pigs move. If we have a lack of consistency of state regulations, in what information states are going to accept, then that's going to be an issue,” Wagstrom says. “Having those regional discussions ahead of time is really important.”

Another new area in FAD response planning this time around has been collaboration with the packing plants and processors.

“Most of the major packers are working with NPPC and other industry organizations, along with CPB, state veterinarians and USDA,” Wagstrom says. “For those issues that had been identified in some of these preplanning tabletop exercises, we can understand how they would function in the case of an outbreak. This is unique to what I believe the industry is doing compared to other countries.”

While this has led to great discussion and collaboration, Wagstrom says the industry still needs to improve on making sure every load of pigs has a Premises Identification Number associated with it and it’s been validated.

“We move pigs so far and so often that if there are any movement restrictions, that's going to be extremely difficult,” Wagstrom says. “I think we probably as an industry rely more on animal movements than other countries do, so that's a challenge.”

NPB has been leading the effort to get pork producers to develop a Secure Pork Supply Plan and verified national PIN for each and every one of their sites, but also to share those plans with state animal health officials. Over the past year NPB has met with several state veterinarians in some of the largest pork-producing states and walked them through SPS and what diagnostic, animal movement and on-farm biosecurity data would be available through the program for them to make decisions.

“It’s not just African swine fever. It’s with any of the foreign animal diseases. The state veterinarians are going to play a key role,” says Dave Pyburn, DVM, senior vice president of science and technology for NPB. “They are going to be the folks on the ground in whatever state or states that this is occurring in at time zero.”

Reaching youth

When the 2019 World Pork Expo was canceled, the live swine show, that is typically held during the event, carried on as The Exposition. Rather than stay quiet, NPB recognized The Exposition as a prime opportunity to revisit biosecurity with youth in the show circuit.

“Youth exhibitors always practice biosecurity,” says Carrie Webster, NPB producer and state communications manager. “They've always done these practices to make sure that their pigs stay healthy, but with everything that's happened with African swine fever in the last year and any foreign animal disease, we really wanted to be sure to connect those dots.”

Nearly 1,400 exhibitors, parents and industry spectators at The Exposition attended the industry panel on biosecurity and farm preparation. The Pork Checkoff, in collaboration with the National Junior Swine Association and Team Purebred — the nation’s largest youth swine organizations — led the discussion.

From there, Webster says the effort has snowballed into county and state fairs and Jackpot shows. In addition to the Champions Guide to Biosecurity booklet, Pork Checkoff also developed a new biosecurity toolkit, that is available both online and in PDF format.The toolkit includes biosecurity videos, informational flyers and social media graphics to share with youth exhibitors as well as a Pork Checkoff Passport, as a way for exhibitors to track their pigs’ movement.

“The passport helps track movements so that youth are more aware of where they've been and where they've gone and who maybe they've gotten in contact with, especially if they're in that Jackpot series, and just being more aware of where they've been and keeping biosecurity in the back of their mind,” Webster says.

Thus far, Webster says Pork Checkoff has received nothing but positive feedback on the youth exhibition biosecurity program.

“The best part about it is really connecting those dots and that better understanding of why. For some youth, mom or dad is telling them how to do something but not necessarily why. There's not that explanation. We're doing it, so they better understand how not to spread disease or how disease is spread,” Webster says. “It really opened up the opportunity for us to have a discussion with them about what African swine fever is, what is a foreign animal disease and why biosecurity is so important.”

Keeping consumer confidence

What is ASF? Is U.S. pork safe to eat? Are my family and pets safe? Is ASF a public human health threat? The Pork Checkoff communications team recognized soon after ASF broke in China, there would be many consumer questions to answer if the virus ever made its way into the country. Over the last year, the Pork Checkoff has developed an array of materials and tools ready to deploy that are aimed at informing and reassuring U.S. consumers.

The main resources that are in the arsenal include an ad campaign for digital, social media and trade media; English and Spanish assets; a consumer website; social media content; videos; third-party spokespeople; proactive/reactive media outreach and messaging to allied partners.

“We’re currently at a yellow-level, elevated threat,�” says Cindy Cunningham, assistant vice-president of communications for the Pork Checkoff. “However, we want to be prepared for a red-level threat, which would happen if ASF is ever confirmed in the U.S. That’s why we’ve created a set of tools that we could immediately use to help ensure consumer confidence in our nation’s pork supply.”

Producer awareness

Finally, all the organizations involved in the past year’s prevention and preparation activities say producer awareness is the ultimate goal. From NPB’s FAD Preparation Bulletin and its pork.org/FAD page to SHIC’s Global Disease Monitoring Report and NPPC's Meat of the Matter newsletter, in addition to hosting numerous meetings, workshops and webinars, education has been at the forefront of their mission.

“We’re definitely in a better position today to deal with a threat such as African swine fever,” says David Newman, NPB president. “That said, we can never be too prepared with a devastating disease like this. What I like though is how much our industry has come together over the past 12 months in a spirit of collaboration to get the job done.”

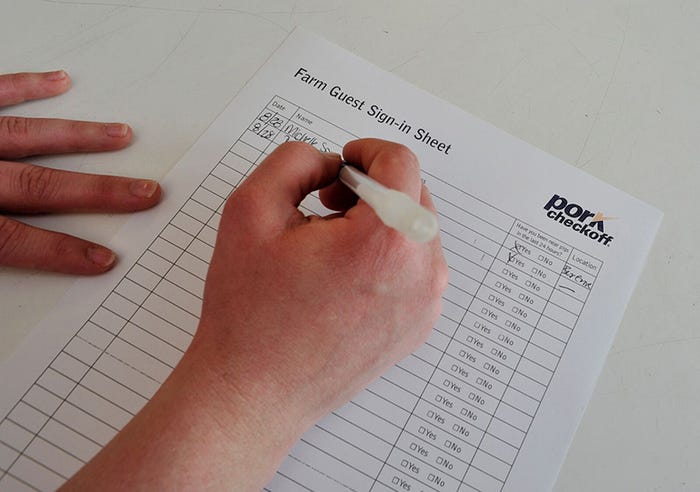

Many producers have started implementing new protocols for having international visitors on farm, not allowing pork products in the breakrooms and increasing insect control and more biosecurity measures around sites’ perimeters.

While there is no data to confirm his theory, Sundberg says he believes at some point in history ASF, CSF or FMD has made it through a port of entry in the U.S., but it’s the heightened awareness and increased on-farm biosecurity today by U.S. pork producers that has kept an FAD from infecting a U.S. pig.

“I think that awareness is something that is growing on behalf of pork producers in the industry,” Sundberg says. “They are the final person on the wall to keep ASF out of the country because if it has gotten into the country, it hasn't infected pigs, and that's the most important piece here is to keep it out of our pigs.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like