Fourteen states put their African swine fever response plans into practice during the four-day USDA exercise.

Over the last year, pork industry members across the country have sat around tables talking through response exercises if African swine fever ever should ever break in the United States. Last week 14 of the top swine-producing states were given the opportunity to test drive their crisis response plans and to see if they could effectively respond to and mitigate an ASF outbreak.

“It gave us, I think, a better perspective of real-world response to this kind of crisis,” says Roy Lee Lindsey Jr., executive director of the Oklahoma Pork Council. “We’ve done tabletops before, we’ve done exercises before where we sat in a room and then somebody said, ‘Ok, so this just happened. Now what are you going to do?’ As a part of this functional exercise, we were able to say, ‘Ok, we’ve issued a stop-movement order. What does that mean? What do we have to do to implement that? Who do we get to enforce that?’”

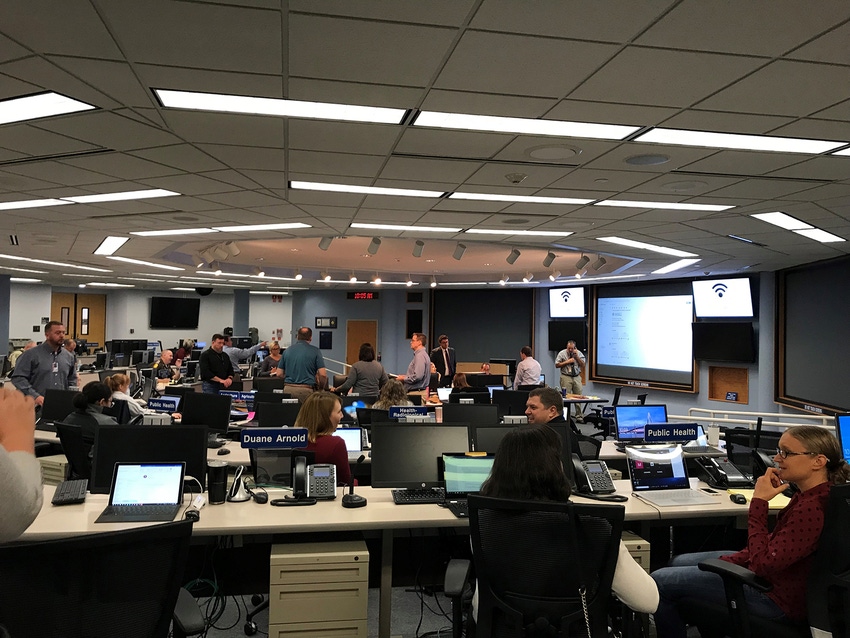

Led by the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service Veterinary Services National Training and Exercise Program, the four-day full functional exercise brought together pork producers, allied industry members, state and federal government officials and even members of law enforcement and the legislature to act out every scenario that would happen in the face of a foreign animal disease outbreak. Each of the 14 states — Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, South Dakota and Texas — participated from their departmental operations centers, initiated the appropriate scale of an Incident Command System and deployed personnel as needed.

While most states like Oklahoma conducted the exercise with one site as the acting FAD break, the state of Iowa “pushed the envelope” further by having a sow farm and two finishing units across three different counties, as well as two packing plants participate.

“I think exercising the extreme stressed the system and it occasionally made producers mad, but I think that’s really the only way to get better,” says Jamee Eggers, producer education director for the Iowa Pork Producers Association. “I’m proud of them for sticking their necks out and really trying to exercise through hard stuff, instead of just talking about it. I think every day we had good details that we worked through. IDALS (Iowa Department of Agriculture and Land Stewardship) and USDA had sought producer input previously so that just led to being able to make really solid decisions and already having a lot of stuff in place.”

After dealing with a highly pathogenic avian influenza outbreak and pseudorabies eradication, Indiana is one of those states that already has quite a few protocols in place before last week’s exercises, including mandatory premise identification.

“Our Board of Animal Health has been pretty proactive, especially in getting into the big systems first to get as many pigs verified on Indiana’s version of the Secure Pork Supply Plan and getting the premise IDs validated as quickly as possible,” says Josh Trenary, executive director of the Indiana Pork Producers Association. “That’s a leg-up for us versus states where they are not mandatory.”

Even with states having some protocols in place for dealing with an FAD outbreak, the exercise unveiled response steps, both large and small, that needed improvement and more clarification. For example, on Monday, when each state conducted an FAD investigation and subsequent coordination and engagement with the National Veterinary Services Laboratory’s Foreign Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory and other appropriate laboratories in the National Animal Health Laboratory Network, Iowa learned it was at capacity with the three breaks.

“Since we were the only state that had three producer players, we really maxed out the capacity for state and federal staff to be doing animal disease investigations,” Eggers says. “Our big takeaway there is figuring out ways to increase that capacity so that if we did have more than one site, or if, as an example, it was found that first positive came through a packing plant or through the diagnostic lab and just all of that epidemiological work that would have to happen and all of the state and federal staff, veterinary staff, to do on-farm foreign animal disease investigations. We’ve got to find a better pathway to increasing our capacity for that.”

On Tuesday, Iowa was the first state in the exercise program to declare a 72-hour standstill for livestock, as well as feed. According to Eggers, North Carolina also tried to stop feed movement, but after producer pushback, allowed feed to move again. Oklahoma had it in their plans to do feed permits, but never actually ordered a feed movement stop during the exercise.

“We discovered that when we did the stop-movement order, we said that we would still allow feed to move. We didn’t want to create a humanitarian issue with animals, and when we said we’re going to permit movements, we said we wanted to permit feed movements,” Lindsey says. “Well, those two things don’t match. So then, which way do we want to change that? Do we want to start permitting feed movements immediately and not wait until we lift the stop-movement order, or do we not need to permit the movements at all? That’s something that we’ve got a note on.”

After Iowa issued its stop-movement, other states followed suit and then the USDA issued a national standstill, which Eggers says created some inconsistencies in when movements could begin again.

“Our key takeaway from Tuesday was we’ve got to work towards more state-to-state consistency on movement. And for producers, if feed is going to be in the movement standstill, we have a lot of work to do to help producers understand what that means and what steps they can take to mitigate welfare concerns on sites if they can’t move feed for 72 hours,” Eggers says.

With Wednesday dedicated to implementing and coordinating depopulation and disposal of infected and exposed swine, Lindsey says simple questions came up during Oklahoma’s exercise such as do we have an excavator near the farm that can dig a hole for mortality management. However, the situation lent itself to inject people on the Incident Command team to make those calls and get real answers now.

Indiana not only requires mandatory premise identification, but every site with 600 head or more are required to get an environmental permit every five years. During Wednesday’s exercise, Trenary says it became clear that the state’s producers not only need to work on making sure their premise IDs are accurate, but also the farmstead plans for the permit.

“Because there’s going to have to be some reference to those, and reference to those in real time, as you figure out where you’re going to do on-site composting that you may have to do in a depopulation event or something like that,” Trenary says. “Making sure all our ducks are in a row on the environmental side is going to be important too, so those references are available to the people that need the information, and it probably wouldn’t be a bad idea to loop an environmental consultant into the discussion too, as you consider mortality disposal options.”

On Thursday, pork industry members concluded the series of exercises, implementing a system to allow continuity of business for non-infected operations within a control area. The biggest bottleneck that day for several states was sampling.

For example, in Oklahoma, officials realized they didn’t have a document in place for the proper way to package samples.

“That wasn’t in our instructions and rather than trying to figure that out, in the middle of an event, we’re going to be able to go back and answer those questions,” Lindsey says. “You know, you’ve got to have packaging available on the farm to put samples in and what that packaging looks like, things like that, that we could do in advance, in my estimation, sets us up far better for success down the road than just sitting around a table talking through what these pieces are.”

Since Iowa didn’t have solid guidance on the number of samples each farm needed to submit in order to achieve a confidence level for permitted movement, they threw out a number to try Thursday. As soon as farms started running through the exercise and requesting permits though, producers became alarmed as calculations were approaching $200,000 to $400,000 per week for sampling.

“We really need some science help and some epidemiological statistic help to determine what’s an appropriate confidence level and appropriate sample collection or sample size for permitted movement,” Eggers says. “There was also a large question about whether or not movement permits are in lieu of a certificate of veterinary inspection.”

According to Trenary, Indiana’s Board of Animal Health, using USDA’s Center for Epidemiology and Animal Health’s guidance, has already set the state’s guidelines for 30 tests per pig site to clear movement. During the avian influenza break, the poultry standard was essentially two samples per site and with the type of testing that is USDA-approved right now for ASF, the state’s laboratories will be looking at a 15-fold increase in sampling, Trenary says.

“We’ve got to follow-up on conversations with our NAHLN lab about how we might be able to bring more resources to bear for them to increase that throughput and there’s obviously some of this stuff on the sample size you want to control because it’s going to be limited by what USDA is able to approve,” Trenary says. This is why Indiana is pushing for pooled samples to maximize available resources.

Despite these hiccups and hurdles last week in the ASF mitigation and response exercise, all three pork industry members say the experience was valuable and producer feedback was positive.

“We’ve received tremendous feedback from our members that were part of our crisis communication plan outreach, both on our text message system as well as our email system,” Lindsey says. “We know the messaging went out. We know they got it and their feedback has been very positive.”

“We have an incredible team in Iowa, and everybody was willing to listen and work together and make decisions. I don’t believe that every state has that really solid relationship between industry producers, state veterinarian’s office, attorney general office, secretary of ag and USDA leadership in the state. I was so proud to see how well everyone worked together,” Eggers says. “This is absolutely about continuous improvement. Growth and learning — this exercise was a fantastic forum for doing just that. Like Roy Lee said, feedback from producers has been positive in Iowa. Every one of them said ‘We learned a lot, and this is how we get better.’”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like