Larry Jacobson’s widespread engineering work with livestock facilities and understanding the odor emissions from these facilities has benefited the entire U.S. livestock industry.

June 5, 2018

U.S. hog producers should be glad Larry Jacobson did not pursue his intended electrical engineering degree when he was an undergraduate at the University of Minnesota in the early 1970s. Not that he couldn’t have made great contributions in that field, but his work as an agricultural engineer changed the way people think about odor and outdoor air quality.

Until two years ago, Jacobson was an Extension livestock housing specialist in the University of Minnesota’s Department of Bioproducts and Biosystems Engineering. Though he worked with all animal species, he says the majority of his time was spent with pork producers.

“In the ’70s when I started, the poultry industry had already consolidated, and I was just at the cusp of the swine industry consolidating,” he says. He remembers visiting the Marlin Pankratz farm near Mountain Lake, Minn., the biggest at the time with 400 sows.

“By the mid-’80s, hogs had consolidated, first with the co-op sow units. I remember visiting with Bob Christensen when he was still in high school; he was expanding with remodeled facilities … there was a lot of interest in facilities,” he says.

The ag engineering department at the time worked closely with veterinarians and “spent a lot of time on the farms with veterinarians, because they didn’t have an engineering background, and most of them realized that,” Jacobson says, “so it was good learning for both of us. How are we going to ventilate this? How are we going to rearrange this?”

Because of the expansion taking place then, “there was a great appetite for housing,” he says. As a result of the expansion and consolidation, “we ended up with this issue around air quality and odor with a lot of animals housed in one site, and it became pretty heated, pretty controversial,” Jacobson says.

The Minnesota countryside was setting up as a battleground of sorts, as county and township boards were seeking expertise into the matter while they attempted to referee battles between hog producers and their neighbors.

Though there was local control of these feedlot issues, Jacobson says the Minnesota Department of Agriculture, recognizing the magnitude of the issue, stepped up and asked what it could do.

Jacobson knew it would take time, but he believed his department could build a model to find out just how much odor was being emitted by livestock facilities.

The model Jacobson’s team created would become known as the OFFSET (Odor From Feedlot Setback Estimation Tool) model; it remains in use today, helping producers calm battles between themselves and the public.

Though OFFSET was developed to aid the Minnesota livestock industry, including swine, it has been used in other states. It is for this widespread impact that Larry Jacobson is being honored as one of this year’s Masters of the Pork Industry.

OFFSET is designed to estimate average odor impacts from a variety of animal facilities and associated manure storages.

Jacobson says the development of OFFSET was a three- to four-year process because there was “no data available of just how much odor is coming off these places.” Jacobson’s team was able to borrow tools from other industries to see how odor disperses from sites.

The first step was developing an olfactometry lab in the basement of the engineering building on the University of Minnesota’s St. Paul campus. Sometimes timing is critical, and it greatly benefited Jacobson’s team’s progress as St. Croix Sensory Inc. from Stillwater, Minn., had an olfactometer and was looking to expand its business. So, the engineering department bought the olfactometer, “and we were their beta-testing unit,” Jacobson says. “It was incredibly good timing because to develop our own would have added another year or two to our work.”

Instead, Jacobson’s team could spend their time developing a proper protocol to collect samples from sites to build a “pretty strong database and plug in the model, and we had it. It was used right away,” he says.

Jacobson says the OFFSET model was widely accepted immediately, and his department remained neutral, “because we understood both sides of the issue. From the pork producer side, they were limited because it was hard to find building sites that were located away from residences where they weren’t affecting neighbors, and most of the pork producers want to be good neighbors. They wanted to have it better smelling themselves.”

Larry Jacobson demonstrates the use of an olfactometer in the lab at the University of Minnesota Department of Bioproducts and Biosystems Engineering. The olfactometer is used to measure the odor concentration of samples brought into the lab from various livestock farms.

High-tech meets low-tech

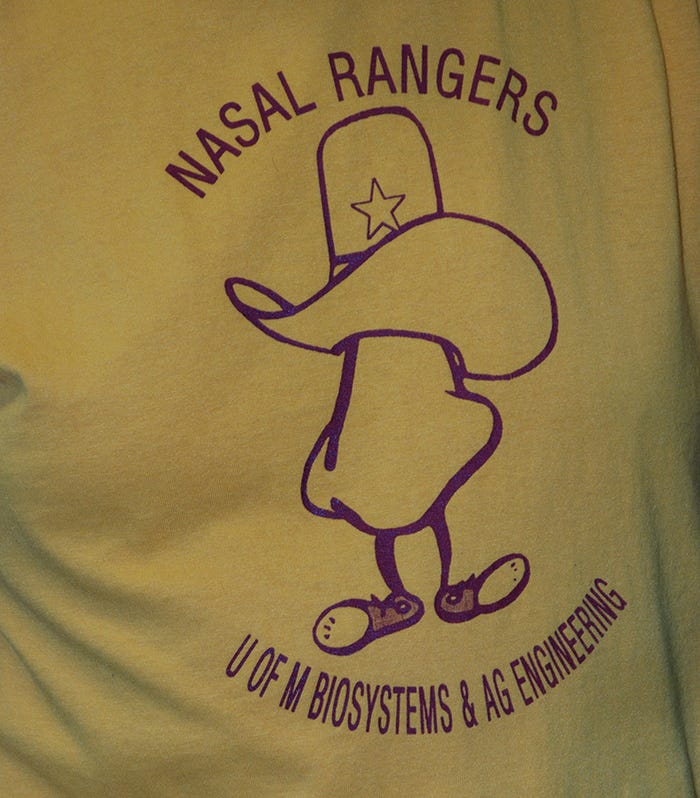

As Jacobson’s team developed the OFFSET model and incorporated the olfactometer results in their lab, they also relied on the God-given technology of the human nose. Jacobson’s team assembled a panel of people with a discriminating sense of smell called the Nasal Rangers. They were taken to farm sites to measure odors released from livestock buildings and associated manure storages.

“We typically would have six to eight people to a site, take source odor measurements of the air leaving the facility, and then we would go downwind at 100 yards, 150 yards, 200 yards, and the people would be lined up maybe 20 feet apart from each other and take a sniff,” he explains. Each Nasal Ranger would record the odor “intensity” (on a referenced scale of 0 to 5) every 10 seconds for 10 minutes, “and we could calculate a measured odor plume for the site.”

“Since we knew what the source odor emissions were, and the weather data from our portable weather station, we could plug this data into OFFSET and generate an estimated odor concentration at various downwind distances that we could verify with Nasal Ranger numbers. This was how we developed confidence in and validated the model,” Jacobson says.

The Nasal Rangers made trips to 20 to 30 farms that housed hogs, dairy and poultry to get downwind odor data that were then compared to OFFSET model results, building more confidence in Jacobson’s team’s methods.

Not just anyone could cut it as a Nasal Ranger; Jacobson’s team evaluated each person who stepped up to join the panel. People’s ability to smell varies; some are hypersensitive, while others have a poor sense of smell. Fortunately, a majority of people are in the middle, and screening methods identified those people.

Nasal Rangers went through one-day training, and Jacobson believes the panel was a cross-section of citizens. They got a relatively small stipend for their services.

Jacobson’s team employed a panel of people who visited farms to measure the level of odor leaving livestock barns. The Nasal Rangers also spent time in the lab using the University of Minnesota’s olfactometer. T-shirts were made to develop team camaraderie.

The same procedures used to select Nasal Rangers were used for selecting panelists in the more controlled atmosphere of the olfactometer lab back on the St. Paul campus of the University of Minnesota, to measure the odor concentration of samples brought into the lab from various livestock farms. St. Croix Sensory has actually trademarked “Nasal Ranger” as the name of the company’s portable olfactometer that can be used in the field.

OFFSET’s development has opened doors for Jacobson to do out-of-state consulting work, as well as to testify in odor nuisance cases as a friend of the court, though he does not seek out that work.

“I see the need for that, and that is part of why we developed OFFSET — to get a settlement, work out some options to try to avoid litigation. That was the goal from the get-go with the Department of Ag, and we agreed with that. … Every case is different, and there are two sides to every story, and some are a combination of the two,” he says.

Large classroom

Though Jacobson never held a teaching assignment at the University of Minnesota, he spent plenty of time in front of “classes” during daylong workshops around hog country in Minnesota for county feedlot officers and other key policymakers to learn how to use OFFSET. “We kind of became the go-to for this,” he says.

It wasn’t long before that expertise was sought beyond the borders of the Gopher State. Michigan, South Dakota and Nebraska were the first states to reach out to Jacobson’s team. He says Iowa had already developed a similar model.

“That’s probably the thing that stands out in my career that I feel the best about,” he says. “It was an issue that really needed and called out for a technical fix, and I think we were able to pull together the best technology; and even today, it’s been 20 years since we published that, and it’s still being used. It needs to be updated, but it still helps a lot of people make decisions on selecting sites for new facilities.”

OFFSET only tells producers and others the amount of odor that comes from specific livestock operations, but then it is up to the producer to find the best odor mitigation practice.

In Jacobson’s eyes, the most effective odor mitigation practice for hog barns is the use of biofilters, but “those are problematic because there are no commercially available biofilters; you can’t just go out to Acme Co. and buy one,” he says. “You have to basically have it custom-made for your operation.”

To be fully functional and effective, Jacobson says the best way to incorporate a biofilter into a barn is to have it considered in the design of the building itself and the ventilation system within. “It is difficult to add it on to an existing facility.”

Jacobson would like to see more odor control technologies available for hog producers, but he says so far they can only reduce a “small percentage” of the odor.

“Odor is interesting in that unless you have a technology that knocks it down by at least 50%, it’s hard to notice the impact, because our sensation is logarithmic, meaning you need to have a bigger impact to notice a reduction,” he explains.

Just as Jacobson sees a need for improved technology for odor abatement, he also sees the need to improve the OFFSET model.

“We would not have to start from scratch, but we need to update our database because we have new facilities and new designs, and there’s been an improvement in dispersion modeling. And the collected weather data are a lot better than they were 20 years ago,” he says.

Even though the battle over odor has raged for as long as there have been livestock operations, Jacobson says the need for information and education is still necessary. “We still need to get the word out about odor, what it is, and what it is not,” he says. “Contrary to what many might believe, the odor coming out of a livestock facility day in and day out is pretty consistent, with the exception of when you are pumping manure — then all bets are off.”

Some of the continuing education has resulted from a better understanding of how odor dispersion is affected by weather patterns. “You’ll hear from neighbors that say, ‘Oh, I know they are doing something different down there [at the barn] and they’re kicking out a lot more odor, because all of a sudden it just knocked me flat.’ No, that’s not the case. The problem is that the weather is stable, and rather than the odor going straight up, it’s moving sideways. … If you tell people, eight out of 10 will accept that. They may not like that, but they’ll understand.”

Jacobson has dispelled the belief that main objectors to stink are urbanites who are seeking “the good life” in the country. “My experience often found it’s much more prominent for the complainer to be a former farmer who used to raise pigs or other livestock and now doesn’t want to smell it.”

Larry Jacobson, retired University of Minnesota professor in the Department of Bioproducts and Biosystems Engineering, receives the Environmental Steward award during the awards reception that kicked off the 2018 Minnesota Pork Congress in downtown Minneapolis. Farm broadcaster and emcee Mark Dorenkamp (left) and 2017 Minnesota Pork Board President Reuben Bode of Courtland, Minn., look on. This award was sponsored by Balzer Inc.

Background in ag

Jacobson’s dairy farm background served him well as he became a specialist in livestock facilities, ventilation, odor and dust control, but that career almost wasn’t.

After graduating from high school in Pelican Rapids, Minn., in 1968, he attended the University of Minnesota-Morris. After two years of pre-engineering classes, he transferred to the main campus in the Twin Cities. He had planned on majoring in electrical engineering, but his interest in ag engineering had been piqued by being exposed to the livestock facilities at the University of Minnesota West Central Experiment Station at Morris.

In 1974, Jacobson completed his ag engineering master’s degree at the University of Minnesota and was offered a position with University of Minnesota Extension. “I had planned on going to Cornell University; they had a new dairy facility there,” he recalls. “But then the Extension position came up.”

When he was hired, there was the stipulation that he would complete his doctorate, “but with the Extension position, I was getting out and talking to the producers. I was really trying to connect with them one on one.” As a result of being on the road as much as he was, he didn’t complete his doctorate until 1983.

After growing up on his family’s 30-cow dairy farm in Minnesota’s lake country, though he enjoyed working on the farm, Jacobson knew he didn’t want to be a farmer. The first in his family to go to college, he had an aptitude for math and sciences, so it seemed obvious to become an engineer.

Early in his career he enjoyed making farm visits, and he was fortunate to travel and make presentations at swine meetings with fellow University of Minnesota stalwarts Al Leman (swine health), Chuck Christians (swine genetics) and Jerry Hawton (swine nutrition). “Traveling with all of them was a real learning experience for me — a lot of exchange of good information,” Jacobson says.

Making individual farm visits would be frowned upon by today’s biosecurity measures, “as I think my record was visiting 13 farms in one day,” he adds.

He took a one-year sabbatical in 1994-95 to Denmark, to work with researchers focusing on environmental, indoor air quality in hog facilities. “That was good timing, because when I came back here, the issues with livestock odors were really heating up in Minnesota,” he recalls.

Family behind the man

Jacobson did not go to Denmark alone. His wife, Jane, and their two sons, Karl and Kurt, became immersed in the Danish culture. Kurt, who was 10 at the time, picked up the Danish language and much later did postdoctoral work in Switzerland after receiving an environmental engineering degree at the University of Wisconsin. He now lives in Madison, Wis. Karl, who was 13 when they were in Denmark, got his biology degree from the University of Minnesota and now works for the Red Cross in the Twin Cities.

Jacobson and his wife do some traveling in their retirement, but they have three Labrador retrievers, which makes it a little difficult to get away. He hopes to get out in the Minnesota fresh air with the dogs to hunt pheasants and grouse.

As the dogs are trying to catch the scent of the birds they’re tracking, Jacobson can breathe deeply of air he spent a career understanding and improving.

You May Also Like