Mycoplasma pneumonia was identified as a cause of pneumonia in pigs in 1965. Mycoplasma is most often mixed with other bacteria — like Pasteurella multocida, Streptococcus suis or Haemophilus parasuis. When this occurs, the pneumonia is referred to as enzootic pneumonia.

July 15, 2012

Mycoplasma pneumonia was identified as a cause of pneumonia in pigs in 1965. Mycoplasma is most often mixed with other bacteria — like Pasteurella multocida, Streptococcus suis or Haemophilus parasuis. When this occurs, the pneumonia is referred to as enzootic pneumonia.

The development of effective vaccines and antibiotics controlled Mycoplasma pneumonia until porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) entered the picture. PCV2 had a devastating effect when it interacted with other pathogens in the lung. Circovirus vaccines put that back in check.

However, the incidence of Mycoplasma pneumonia appears to have increased in recent years. There have been many theories for this occurrence. Vaccine failure is frequently cited. There are many factors involved; consider the entire picture when looking for effective solutions.

Case Study No. 1

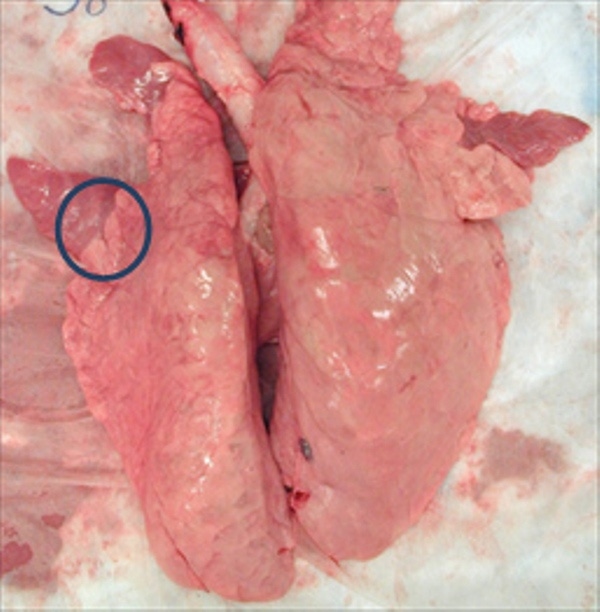

In a 2,500-sow, farrow-to-finish farm with three-site production, pigs spend nine weeks in the nursery and 18 weeks in the finisher. Over the last two years, occasional postmortem and laboratory examinations have identified lungs and lesions with Mycoplasma pneumonia. The farm is a mycoplasma-positive farm using a one-dose vaccine for control.

The farm is also positive for porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome ( PRRS) with seroconversion occurring late in the nursery. In the last six months, death loss in the finisher has increased from 4% to almost 6%. Diagnostics have detected increased mycoplasma activity as well.

We revaluated mycoplasma control protocols, switching from one vaccination at weaning to two vaccinations. The first dose is given at two weeks postweaning and the second dose at five weeks. We also added a pulse dose of lincomycin in the feed for two weeks starting after the third week in the finisher. Microscopic lesions in the lung and serology indicated some mycoplasma exposure early in the finisher phase.

Since then, we have seen some improvement in death loss back to 4%. We still have some PRRS coming from the sow farm and we hope that efforts will further reduce death loss.

Case Study No. 2

A 5,000-sow, farrow-to-finish farm utilizes wean-to-finish barns. It is a PRRS- and Mycoplasma-positive farm. Postmortem and laboratory work have confirmed Mycoplasma pneumonia at 16 weeks of age. The farm is using a two-dose mycoplasma vaccine, which has worked well on many other farms with similar health status.

However, we were concerned that something had changed to affect the farm’s health. We blood-tested a cross-section of different parity sows and gilts to determine mycoplasma titers. We saw significantly higher titers in the replacement gilts headed to the sow farm and concluded there was some circulation of mycoplasma within the gilts in the isolation barn. We felt that gilts were shedding mycoplasma upon entering the sow herd, resulting in an unstable sow herd.

To control this problem, we are focusing on early exposure of the replacement gilts to mycoplasma by exposing them directly to cull gilts and sows. The farm utilizes a

100-day isolation period. We are exposing the gilts within the first two weeks following arrival into

isolation. We are also adding two doses of vaccine and a pulse dose of

lincomycin to the isolation feed for two weeks prior to the gilts being brought into the sow herd. We have had one group of gilts go through the isolation with this new protocol. Blood testing indicates a lower mycoplasma titer within this group. We have good exposure to the bacteria and a declining titer indicating reduced shedding.

It’s too early to assess the impact of our mycoplasma control program on finisher health. But it does appear that we are reducing gilt shedding as gilts enter the sow farm.

Summary

Regardless of the disease causing problems in your pigs, successful control protocols will take into account more than the brand of vaccine used and timing of vaccination.

We know and understand what it takes to control Mycoplasma pneumonia. However, disease dynamics within herds are constantly changing. A small change in isolation protocols or an undetected change in health of the replacement gilts can have an effect downstream to the rest of the farm that can be quite dramatic.

You May Also Like