The big three contributors in CVS’ clientele of herds in the mid-south and southern United States consist of rotavirus, clostridium and coccidia, often linked to secondary infections of E. coli

In these times of tight margins, every 50 cents to a dollar earned from every pound of pork produced is important to the financial stability of a hog operation, says swine veterinarian Doug Groth of the Carthage (IL) Veterinary Service, Ltd. (CVS).

“This year we are just trying to make more money to make up for the last couple of bad years,” he said in a talk at the CVS 20th Annual Swine Conference at Western Illinois University in Macomb, IL. “The goal is all about getting pounds of pork out the door.”

In the past few years, baby pig diarrhea has emerged as a major contributor to burned-out pigs and elevated preweaning mortality, Groth says.

Rotavirus Tops the List

The big three contributors in CVS’ clientele of herds in the mid-south and southern United States consist of rotavirus, clostridium and coccidia, often linked to secondary infections of E. coli.

“Rotavirus Type A has been the traditional rotavirus we have seen for a long time, and the oral vaccine has been effective in the sow herd to reduce suckling pig diarrhea,” Groth states.

Complicating that scenario has been the appearance of Type B and C rotavirus, which produce the same watery diarrhea and vomiting as Type A in young piglets, but which can’t be reproduced in the laboratory to determine their true pathology or means of causing disease, he says.

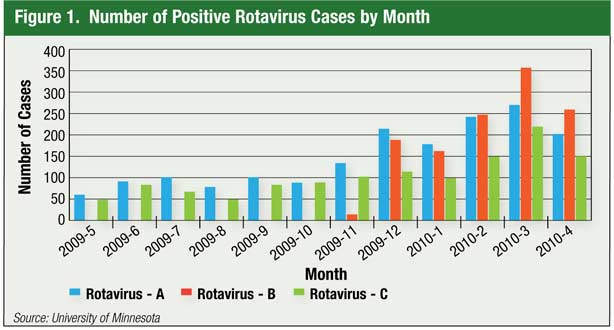

Summary data from the University of Minnesota Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory for 2009-2010 (Figure 1) shows that cases have spiked in the last 6-12 months. “That reflects what we have been seeing in our practice, a doubling of cases that shows this is a significant disease factor in the industry,” Groth says.

Equally troubling is the fact that once pigs are infected with rotavirus, there is severe damage to intestinal villi, (tiny hair-like structures in its intestine that help the pig retain fluids), with this viral infection, which produces the watery diarrhea and severe dehydration.

“The infection just has to run its course, and work its way through the pig. You treat that type of scours with antibiotics for the secondary problems like E. coli. This provides time to restore the damaged pig’s villi,” Groth explains. Injections are sometimes easier to administer than picking up pigs for the oral drench and waiting that extra second to make sure they have swallowed it, he adds.

Feedback is one of the standard practices for rotavirus control. Common practice is to grind up intestinal tracts from pigs that have died from the disease, mix in scour material and feed the contents to sows before farrowing. This helps establish good immunity in sows and provides protection to the piglets via colostrum.

“This method still works for traditional Type A rotavirus, but we have found that it does not provide very good immune generation for the Type B and C strains,” Groth points out.

All of the types of rotavirus described typically strike at 2 days of age. If the pigs are 3-4 lb., they have a better chance of surviving than if they are 2.5 lb. or less, he explains.

Clostridium, Coccidia Causes

Clostridium bacteria (Type A and difficile) are also frequently identified with rotavirus. When these two are linked, it usually means death for the piglet. Clostridium perfringens Type A can be treated with autogenous vaccines or antibiotics with mixed results.

A third piglet type of scours is due to coccidia, a parasite that produces scours at 7-8 days of age or older. Sanitation sometimes produces mixed results, but power wash, disinfect and dry crates to achieve maximum results and attempt to prevent transmission from one litter to the next, Groth suggests.

Coccidia produces spores that can persist in the environment for long periods. High concentration of bleach along with vigorous cleaning can beat down the spore population. Flaming crates using an LP torch to achieve high temperatures is an extreme measure to kill spores and other bacteria, he suggests.

An oral paste product called Marquis from Bayer Animal Health has produced the best results. “It is the only thing we have found that works to prevent coccidia,” he says. This product is available by prescription in swine, due to off-label use.

Accurate Diagnosis is Critical

Not every case of suckling pig diarrhea can be traced to a disease pathogen, according to Groth. The sow may be sick or the energy levels of her feed could have changed — both of which can affect piglet ability to absorb nutrients and result in scouring.

That’s why the first order of business when scours appear is to determine whether it is disease- or management-related. Perform a few necropsies, send tissues to the diagnostic lab and obtain a good workup that will provide an answer, he says. The lab is best equipped to perform both bacterial and viral isolation assays. The goal is to find the primary pathogen so a course of treatment can be prescribed.

“If there is a lot of diarrhea litters, the scours could be due to Transmissible gastroenteritis (TGE),” Groth says. “At first, it may just affect a few litters, but in a very short time it will become very explosive — the whole farrowing house will be scouring and it will smell bad,” he explains. TGE is still typically a wintertime virus carried by birds. Most U.S. herds are very susceptible to TGE because they haven’t had it.

Management Factors

The severity of the nursing pig diarrhea challenge can depend on the level of care or farrowing house management. The facility, staff and stressors each play a role.

Make sure farrowing rooms are set up prior to loading sows. Heat lamps should be positioned, heat mats warmed to 85-90°F and hot boxes cleaned and disinfected. Mistral powder can be used on mats and in boxes to help dry off pigs.

“With the same genetics at two different farms, there can be a different incidence of scours, and it often ties back to people and individual pig care,” Groth says.

In Professional Swine Management (PSM) sow farm systems, the goal is to aggressively focus on individual pig care as young at Day 1-2 to find those one or two pigs starting to scour. Sometimes a small pig in the litter or one that is nursing a hind teat will start scouring, while the rest of the litter looks perfectly fine. If the whole litter is scouring the next day, that’s a much bigger challenge to correct, he notes.

At the first signs of scouring in a litter, Groth suggests flagging the litter and creating a scour treatment card. All pigs in that litter are treated for scours for three days. If there is a response during treatment, that is noted on the card. If there is no response, a different antibiotic is tried. Groth suggests treating piglets one extra day after scours dry up to ensure health.

Watch for yellow staining on pig’s butts as a sign of scours, but don’t be fooled if that is observed in full-bodied pigs actively nursing. Pigs can look healthy one day and still have scours and nurse, but not be absorbing nutrients and look dehydrated the next, he warns.

At PSM farms, preweaning mortality ranges from 8-12%, but it can quickly jump much higher, even to 25%, with severe cases of rotavirus. The goal is to hold mortalities under 8%.

At weaning, a lot of scouring litters will have recovered to become productive pigs, but they may average a pound or two less. Others will survive, but never fully recover to become viable pigs. It is these pigs that should be humanely euthanized, Groth says.

Sometimes pigs are just shy of meeting that 8-lb. minimum weight requirement at 21-day weaning. They will often be placed on a nurse sow until 25 days of age. “With that extra four days, if they definitely are not weighing 8 lb., then they are not going to be in the production flow system,” he emphasizes.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like