Details of biosecurity plan often neglected.

Biosecurity is nothing new, and Jean-Pierre Vaillancourt said it has been in practice for thousands of years. “We have not invented anything,” he said, “and the reason that we have been doing that [using biosecurity measures] for so many years is that it’s been working, and it’s because it’s scientifically sound.”

Threats of diseases have put U.S. hog producers on edge over the years, and on high alert against the pathogen du jour. From porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome to porcine epidemic diarrhea virus causing herd losses, and African swine fever threatening other parts of the world, hog producers look for any advantage that a biosecurity measure will give them in keeping their herds healthy.

“I challenge you to find a measure of biosecurity that does not have something to do with reducing the contaminant, reducing the source of contamination or separating the healthy animals from the source of contamination,” Vaillancourt, a professor at the University of Montreal, told a packed house at the June Iowa Swine Day on the Iowa State University campus in Ames. “They’ll talk about internal biosecurity, external biosecurity, biocontainment, all these things. It’s nice, but at the end of the day, all we’re trying to do — wherever the site — is to reduce the amount of potentially contaminated material or animal or equipment, and to separate it from healthy animals.”

Giving the audience a history lesson, Vaillancourt shared how society handled lepers in the 15th century. “They had what they called a mass of separation,” he said. “They explained to the individual that was affected how to go and get water without contaminating the water for others. They explained how to stay away; to even say if people question you and you’re in the prevailing winds, make sure the wind does not go from you to them. … This was the 15th century, so we’ve known for a long time how to prevent diseases.”

Production in hog-rich areas may be the worst enemy of herd health, violating the principle of separation, as Vaillancourt presented research data showing that the risk of disease infection grows the closer a farm is to an infected farm. When poultry farms are less than 1 kilometer, or 0.6 mile, away from each other, there is two times more chance for salmonella to be spread; four times for Newcastle disease, six times more for E. coli, 35 times more for avian influenza, and seven times more likely that PRRS will be spread to a naïve hog farm.

He pointed to Mycoplasma research done in 1985, where the researcher demonstrated that two risk factors associated with reinfection are where the farm is and the size of the neighboring farm. “That was 20th-century stuff, so what have we done since 1985?,” Vaillancourt asked. “We’ve increased the size of the neighbor, and we got closer to the neighbor.”

Vaillancourt acknowledged that larger and closer farms may make financial sense for producers, while also suggesting producers need to take a different look at biosecurity. “A lot of things are changing, but essentially what we’ve been doing is increasing the infection pressure per square miles,” he said. In addition to wind potentially bringing diseases to farms, regional density also brings more insects, more wildlife, more people, and more equipment that is moving and potentially carrying pathogens. “All of that is increasing infection pressure,” he said.

With the pathogen load risk continually increasing, Vaillancourt said he feels producers need to more closely examine their biosecurity protocol, suggesting that the finer points often get overlooked.

Give pathogens the boot

Often preached is maintaining a line of separation between the “dirty” side and the “clean” side, and while many farms provide a boot-changing station or even a hand-wash station, he said the stations may not be used correctly — or at least not most effectively.

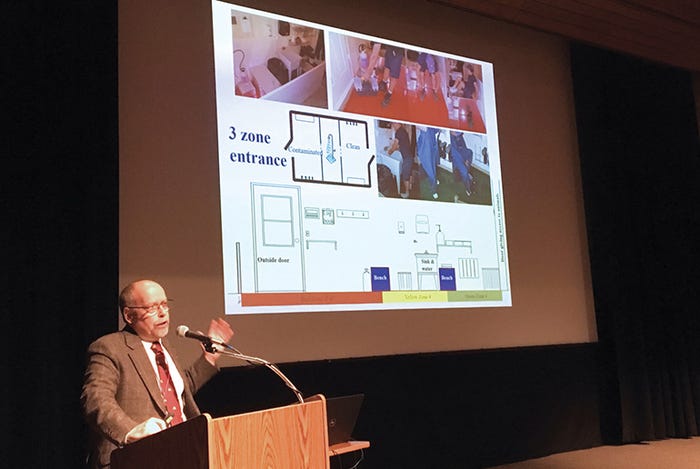

A three-zone system, which many farms have with a shower-in and shower-out setup, can be effective — again, if used properly.

Even farms not requiring showering can use a three-zone system to attempt to prevent pathogen spread, providing an area of about 8 feet between the outside door and the first bench (red zone; see slide above). Footwear worn from the outside is removed and left on the red zone side of the bench. Once in the yellow zone, Vaillancourt explained, stocking-footed barn workers can wash their hands. There is another bench between the yellow zone and the green zone (the clean side), and the barn workers can swing their legs over the bench to put on clean boots to then proceed into the barn.

“Technically, even if you just have a line, you should be able to go from potentially contaminated boots, changing the boots; and as you go over the line and have non-contaminated boots, you should have no contamination,” he said.

Wanting to see how real the contamination from boots can be in a hog barn, Vaillancourt conducted a study by recreating a contaminated environment using a bioluminescent bacterium. What he found was that four different scenarios for changing boots — going from one zone to the next, in the contaminated zone, in the clean zone, and not changing boots at all — played a role in the amount of contamination that occurs.

The best option, leaving the outside boots on the dirty side, showed that contamination stopped at the line of separation. The middle scenarios — in the contaminated zone or in the clean zone — showed varying amounts of contamination that would carry through, potentially to the animals. Not surprisingly, not changing boots at all showed the greatest amount of risk of contamination reaching the herd.

“Changing boots the wrong way will reduce contamination, but it certainly does not eliminate it,” he said. This idea may lead producers to solely rely on a footbath. “All you need to do is add a footbath, so if you mess up a little bit, you go through a footbath and there you go. … Except that in reality, footbaths actually increase contamination” he said, because people either do not use them properly or they are not maintained adequately.

He referred to a study by Purdue University’s Sandy Amass that found scrubbing visible manure from boots significantly reduced bacteria on boots, but simply walking through a footbath does not reduce bacterial counts. This same study found that scrubbing visible manure off in a water bath is as effective at reducing bacterial counts as scrubbing manure off in a bath with disinfectant. This study also found that to meet the standard of disinfection, boots need to be scrubbed manure-free, and then soaked in a bactericide-fungicide-virucide product for five more minutes.

“There are many good products, such as quaternary ammonium and phenol, if they’re used properly,” he said, “but we neglect the science aspect of it.” He said it has been found the “bacterial load” actually increases after only three hours of footbath use. “We always say to change it daily, or when you feel it’s appropriate. Well, daily won’t cut it.”

Vaillancourt suggested that if producers are attached to footbaths, that they should “try to go with dry bleach, and try to respect the principle of separation, because essentially a footbath should be a bit like the shower, right? The difference between this setup and a footbath is that here, you’re going to walk through the footbath from one zone to the other zone,” he said. “I mean, the principle is simple. Keep things separate. If you have to step in something and go backwards, you have not accomplished anything.”

Doesn’t need to be high-tech

Sometimes the simplest measures can help in the biosecurity fight, such as providing coveralls for visitors to the farm. A study that Vaillancourt did in North Carolina where poultry farms were having issues with Mycoplasma gallisepticum found that farms providing coveralls for visitors were much less likely to become positive for the bacterium.

For a farm to be as biosecure as possible, there needs to be buy-in from the entire farm, regardless of each person’s duties.

“You need to have good communication, so that everyone knows what they are supposed to be doing,” he said.

“People at the bottom, doing the most basic task, they feel they are not as important — but for biosecurity, they are very important.”

Getting all workers involved in the decision-making for the biosecurity plan can also go a long way in getting the plan implemented properly. “If it’s their idea, they are more apt to adopt the measures,” he said.

Keeping the biosecurity plan simple will also aid in implementation.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like