Blueprint: Good sanitation in the farrowing house is always good advice, but it may be especially critical in control of this syndrome.

November 7, 2018

By David Knudsen, DVM, MS, DACLAM, South Dakota State University Animal Disease Research and Diagnostic Laboratory

In a routine walk-through of the farrowing unit, multiple litters of newborn pigs are noticed to have mild diarrhea and dehydration, and seem to be set back in growth from cohorts of similar age. The effect seems to vary widely within a single litter, but all pigs are still alert, active and nursing well. Sows are unaffected.

Over the first week, the diarrhea subsides and pigs recover, but they may not reach weight goals for weaning with the remainder of the age group. Two pigs were sacrificed for necropsy examination, and the only gross finding was a clear, fluid-filled swelling in the membranes around the spiral colon. This lesion is termed mesocolon edema syndrome, and is a common cause of transitory diarrhea in newborn pigs.

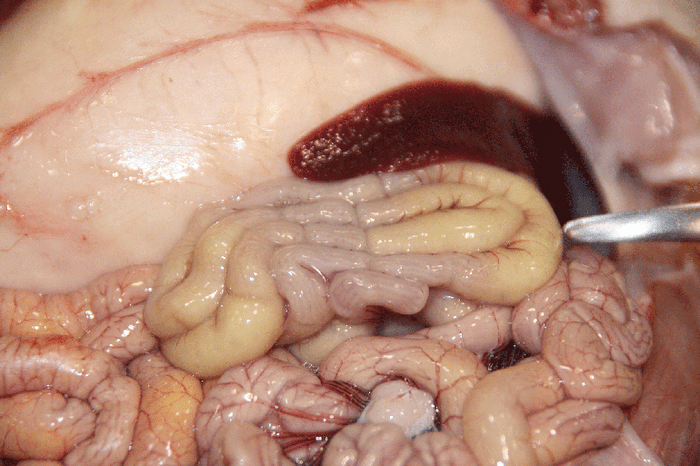

This is the normal spiral colon of a 3-day-old pig.

Mesocolon edema syndrome is characterized by localized edema and inflammation of the mesocolon around the spiral colon of pigs less than 2 weeks of age. Typical affected pigs may show transitory loose stools and somewhat slower growth in the neonate period, and may be more susceptible to other opportunistic or primary pathogens. In the photo above, the normal spiral colon (at tip of scissors) of a 3-day-old pig has loops of colon closely opposed in a spiral arrangement.

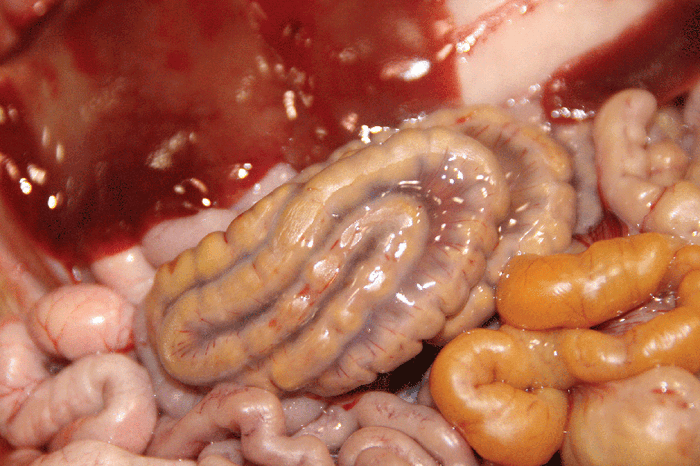

The photo below shows MES in another 3-day-old pig, with clear edema fluid accumulated within the supportive tissue (mesocolon) around and between loops of the spiral colon. This edema can take on a jelly-like consistency and can develop to extreme levels before subsiding.

This photo shows mesocolon edema syndrome in a 3-day-old pig, with glistening, jelly-like edema surrounding the spiral colon.

As the animal recovers, the edema slowly resolves but can still be observed microscopically for two to three weeks. By itself, the syndrome does not result in permanent damage to colon function, but may result in some loss of water resorption from the feces during the course of the disease, accounting for transitory diarrhea.

Clostridium association

Although the actual cause of lesion development is controversial, the syndrome is strongly associated with toxin production by either Clostridium perfringens (genotype A, often with β2 toxin production) or Clostridium difficile. It is thought that when newborn pigs are born and initially colonized by bacteria, one or both of these clostridial bacteria can colonize the colon first and start elaborating toxins, which are absorbed and transported into the lymphatic and blood vessels of the colon.

These toxins can then cause local damage to the lining cells of vessels (endothelium), which leads to fluid leakage from these small vessels into the surrounding mesocolon and the observed mesocolon edema.

Case archives of the South Dakota Animal Disease Research and Diagnostic Laboratory over a 16-year period (2002 through 2017) were searched for newborn pig cases, less than 10 days of age with a history of diarrhea and with submitted fresh colon available for culture.

Over that period, 1,576 cases were identified, and 929 of those cases (58.9%) were diagnosed with MES. From these MES cases, 576 cases (62%) had C. perfringens only isolated, 37 cases (4%) had C. difficile only, 223 cases (24%) had both organisms, and 93 cases (10%) had neither organism identified.

Of those cases with C. perfringens alone or in combination (799 cases), additional genotyping was performed in 663 cases; all isolates were identified as genotype A, and 468 cases (59%) had a C. perfringens isolate with the gene present for β2 toxin. Roughly 65% of cases also had concurrent infections in the small intestine, including porcine rotavirus (types A, B and/or C), E. coli, or Salmonella sp.

Over the 16-year period, there appeared to be a gradual increase in incidence of C. perfringens type A association, and a gradual decrease in demonstration of C. difficile. But whatever the origin of toxic bacteria, the appearance of this syndrome in nearly 60% of diarrhea cases in newborn pigs at our lab is significant.

Diagnosis through pathology

Diagnosis of MES is based on gross and microscopic pathology of the spiral colon, along with ancillary anaerobic culture and genotyping (C. perfringens), and immunoassay for typical toxins (C. difficile). It is also important to test the small intestine by histology, culture, fluorescent antibody and polymerase chain reaction methods for other bacterial and viral agents of enteritis typical of newborn pigs.

Diarrhea syndromes in newborn pigs are often multifactorial, and a complete understanding of the various diseases involved in specific cases is important in recommending treatment and control measures.

Probably the most important control measure for MES is sanitation in the farrowing crate. Infection of newborn pigs by one or more of these clostridial bacteria can happen within minutes or hours of birth, and is a function of colonization into the piglet’s naïve intestinal tract. Even before nursing and receiving colostrum, the newborn pig has exposure to the environment in the farrowing crate and skin contaminants from the sow, and it is also subjected to other environmental stresses.

By minimizing environmental contamination of fecal clostridia, the exposure and colonization of newborns can be reduced. Before the sow is introduced to the crate, the crate and flooring should be thoroughly disinfected with products able to kill both bacteria and clostridial spores. Sows should then be washed completely, paying extra attention to the udder. If possible, the sow should be washed again just prior to birth of the litter. The goal of this sanitation is to minimize fecal contamination and bacterial load in the piglet’s environment during the first hours of birth.

Other measures for prevention and control that have been suggested include antibiotic prophylaxis and vaccination. The idea behind antibiotic prophylaxis is that feed-grade antibiotics, given at recommended dosages, will suppress clostridial shedding from the sow and minimize exposure of the newborn pigs. This approach has not been verified in research trials, and is not recommended in light of new guidelines for antibiotic usage.

Vaccination of sows and gilts could be an option, but available vaccines against C. perfringens type A are not toxoids, directed against the toxins themselves. Instead, they are based on bacterial somatic antigens, which may suppress colonization in the piglet after colostrum ingestion and uptake, but will likely do nothing to protect the newborn against initial colonization.

MES key in newborn diarrhea

At our lab, MES has historically been an important factor in diarrhea in newborn pigs, with 58.9% of pigs less than 10 days of age having MES as a primary cause or associated factor of diarrhea. Individual cases stand out with the syndrome alone, but roughly 60% of MES cases over the past 16 years have also had concurrent small intestinal disease at the time of diagnosis.

It may be that MES, as an indicator of stress and environmental quality, can predispose newborn pigs to other enteric pathogens, and result in increased morbidity and fallback rates. Good sanitation in the farrowing house is always good advice, but it may be especially critical in control of this syndrome.

You May Also Like