Weaning is a defining moment in a pig’s lifetime performance. Overall, gastrointestinal disorders are a major drain to profit margins in animal production. Adam Moeser, D.V.M. Ph.D. at Michigan State University, says gut function and susceptibility to disease is multifactorial and involves interaction between pathogens, pigs and the environment.

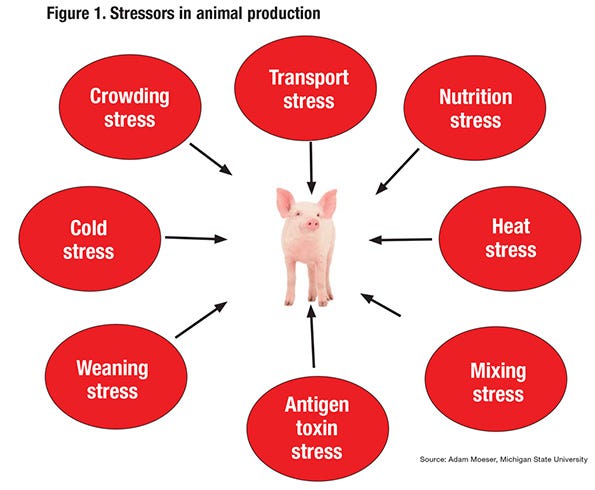

His years of research have shown that the presence of pathogens alone are insufficient to initiate disease processes. However, environment influences, such as stressors present in the production system (refer to Figure 1), can put major pressure on the immune barriers and open the pathway for disease to invade.

While each piglet endures some anxiety during the weaning process, minimizing the stress during this time can boost immune function, which contributes to efficient growth. Christopher Chase, D.V.M. Ph.D. at South Dakota State University, says research has shown that physical and psychological distress can muffle the immune system in animals, which ultimately leads to increased occurrence of infectious diseases. Although the message seems like a broken record, minimizing stress is essential to avoiding weaning growth lag by nurturing healthy pigs.

Protecting the pig starts with the gut. The development of the gut immunity can dictate the response of the pig to future pathogens. For hog producers, there are several ways to reduce the stress load of the young pig, including starting with a better understanding of the dynamics of the gut and its essential role to the immune system.

Gut fundamentals

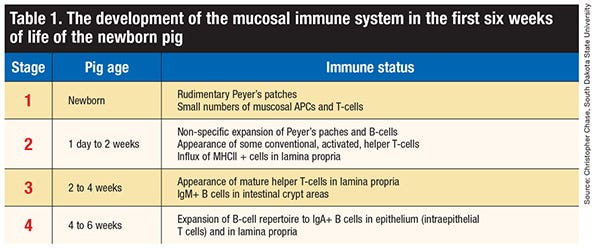

Chase says to imagine the digestive system of the body as a hollow plastic tube with the food digested in the hole of the tube and never entering the solid plastic material. Within the plastic barrier, layers of defense control the immune response. The mucosal immune system provides the first immune defense barrier for more than 90% of potential pathogens in the gastrointestinal tract. It not only protects against harmful pathogens, but also helps tolerize (makes it so the body doesn’t react) the immune system to dietary antigens and normal microbial flora, which are essential for growth and development. The mucosal immune system develops in the first six weeks of life of the newborn pig (refer to Table 1).

As a major player of the immune system, the epithelial cells in the intestine represent the biggest part of the immune system and the largest interface between the pig and the outside world. The single layer of epithelial cells performs important simultaneous roles by absorbing efficient amounts of nutrients and water and transporting electrolytes, while still providing a barrier from the trillions of bacteria, antigens and toxicants, Moeser explains.

Explaining further, Chase says one thing that protects the pig in the respiratory and digestive tract is an antibody called IgA. It performs an imperative task in immunity at the mucosal surface by sticking to infectious agents and preventing them from attaching to the epithelial cells.

Environmental factors can significantly influence the gut associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) located in the mucosal immune layer. Chase says the GALT of the pig is poorly developed and not completed usually at the time most commercial pigs are weaned at age 14-24 days. He adds the environmental influences are greater immediately after birth and at weaning. At birth, colostrum is important for the development of the gut. It is also contains high levels of transforming growth factor that has anti-imflammatory effects and accelerates the IgA antibody. Colostrum also helps in the development of the normal microbial flora. At weaning, the risk for infection can also be increased by environmental factors. Since the pig is no longer nursing, the maternal milk that moderates the immune responses is not available. This can throw off the active immunity balance of a weaned pig. Chase says the magnitude and severity of this “weaning” GALT crisis is dependent on how much the immune system expands during the preweaning period.

Keep the gut calm

Typically, the gut of a wean pig will overreact. Chase says, “The intestine tract in the young pig is doing a lot more things besides absorbing and secreting. In a way, it is also the eyes of the immune system as well.” So, anything a hog producer can do prior to weaning the pig to send the correct signals to the epithelial cells instructing them not to overact will lead to healthier pigs not susceptible to disease, Chase says.

In order for the immune system to function at an optimal level, it must be fed the proper balance of nutrition, including the key vitamins and trace minerals — vitamins A, C, E and the B complex vitamins, copper, zinc, magnesium, manganese, iron and selenium. Chase says establishing a solid creep plan is a good starting point, with short chain fatty acids that fuel the epithelial cells. Although the research is in its infancy for pigs, there is a possible benefit to introducing probiotics and prebiotics that can produce metabolites that enhance the good bacteria in the gut. However, Chase warns more research on these products needs to be completed before their full nutrient value potential is completely understood.

In addition, the route of vaccine administration can be significant for producing mucosal immunity, Chase says. “To induce secretory IgA production at mucosal surfaces, it is best for the vaccine to enter the body via a mucosal surface. This can be accomplished by feeding the vaccine to the animal, aerosolizing the vaccine so the animal will inhale it, or by intramammary exposure,” he explains.

The actual age at which the pig is weaned is truly an individual farm decision. Still, it is important to recognize that research conducted by Moeser on how gastrointestinal dysfunction induced by early weaning is attenuated by delayed weaning and mast cell blockade in pigs shows that early weaning around 19 days of age can cause additional distress. In nature the weaning process is more gradual than the modern production practices. At the time of weaning, piglets face sudden changes in environment and diet, transportation stress, and an increased exposure to pathogens, along with fighting for social hierarchy and maternal separation.

While the magic age and actual procedure is heavily debated, it is necessary to acknowledge that Moeser’s research confirms that the abruptness of early weaning can have a harmful impact to the gut and prompt intestinal barrier disturbance. In pigs weaned at age 18 days, Moeser and his research team found a significant elevation in intestinal permeability or compromise barrier function 24 hours later. In comparison, in pigs weaned at 28 days of age the response in gut permeability was remarkably different, with a mild elevation in intestinal permeability 24 hours after weaning. Additionally, Moeser found late-weaned pigs (28 days of age) had a robust increase in cortisol a day after weaning when compared to the early-weaned pigs.

In general, the anxiety triggers disruption to normal intestinal function of the early-weaned pigs, which can play a significant role in post-weaning enteric disorders. Taking the research a step further, Moeser’s team tracked the long-term effects of early-weaning stress on intestinal permeability. Although the intestinal permeability declines in all pigs in the post-weaning stage, it remains elevated at a much higher level than the late-weaned pigs. Moeser says, “This indicates that there was a persistent long-term change in the development of the gut barrier just by pigs weaned at different ages.”

The research team also investigated the impact of early-weaning intestinal response to an infectious challenge, since those pigs had a more compromised barrier. In the experiment, both late- and early-weaned pigs were introduced to subsequent enterotoxigenic E. coli. Four days after the challenge, the late-weaned pigs recovered, but the early-weaned pigs had a marked intestinal injury in response to this dose of enterotoxigenic E. coli. Looking at immune response, the late-weaned pigs had robust response to the E. coli whereas the early-weaned response was suppressed.

In summary, Moeser says early-weaning stress effects lifelong gut barrier function by:

immediate and long-lasting disturbance in intestinal barrier function

heightened responses to late-life stress challenges

heightened response to late-life infectious challenges

suppressed immune responses to later-life lifelong challenges

Taking the research a step further, Moeser’s team found pigs less than 21 days old maintain a higher number of mast cells in the gut, which has a major effect on intestinal barrier integrity. Mast cells are important to immune response in pigs and other animals, Moeser says. Investigating mast cells, the scientists found mast cells play a critical role in intestinal permeability in early-weaned pigs. Specifically, early-weaned piglet intestinal mucosa had enhanced mast cell degranulation compared with late-weaned intestinal mucosa, meaning that intestinal tract would have more inflammation and be more “leaky.”

Moeser says his research has shown common production stressors have a bearing on the intestinal barrier and gastrointestinal physiology. Stress increases intestinal permeability, affects mast cell activation and increases infectious challenges. Moreover, he adds, this can influence feed efficiency through impaired digestive absorptive processes, persistent gastrointestinal immune system activation or microbiome changes. These are all factors that can change the gastrointestinal physiology and negatively impact the way a pig processes nutrients.

Eliminate time off feed, water

The minimal time the pig is off feed and water is really important. Certain management practices need to be adjusted. Shorter transportation time and less movement of pigs would reduce the amount of time away from feed and water.

Good-quality feed that is similar to the creep feed and highly digestible will also help reduce the feed consumption lag time. Chase says, “The higher the digestibility is, the more likely that the gut of the weaned pig will be able to absorb.”

Many times the importance of keeping the pig hydrated is overlooked. Clean water should be available at all times. Although clean water may be easily accessible, it does not guarantee the newly weaned pig knows how to locate it upon arrival to a new facility. Water is necessary for the immune cells to travel, to absorb things and get to the surface. The IgA has to be secreted. “If the animals are dehydrated and the secretions are real thick or it can’t get out, it does not do the pig any good,” Chase explains.

Maintain a healthy microbiota

Having a healthy microbiota is a big deal, Chase says. The intestinal tract contains the most diverse community of bacteria — known as microbiota — that plays a fundamental role in deterring pathogen colonization and infection. Removing the piglet from the sow’s milk leaves it highly susceptible to enteric disease, partly because it upsets the balance between developing beneficial microorganisms and the establishment of intestinal bacterial pathogens.

Chase says the administration of oral antibiotics can alter the community because antimicrobials don’t know the good from the bad and could eliminate the good bacteria in the gut. Therefore, he recommends limiting oral antibiotics at weaning time.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like