Swine nutrition is changing. The once dominant corn-soybean meal diet has given way to a more diverse list of ingredients that few could have imagined just five years ago. Some changes have been dramatic, even painful, but ultimately essential for survival.But the use of “non-traditional” ingredients in swine diets is more complicated than simply bringing them to the feedmill and asking a swine nutritionist to have a go at developing a new generation of diets.

January 15, 2013

Swine nutrition is changing. The once dominant corn-soybean meal diet has given way to a more diverse list of ingredients that few could have imagined just five years ago. Some changes have been dramatic, even painful, but ultimately essential for survival.

But the use of “non-traditional” ingredients in swine diets is more complicated than simply bringing them to the feedmill and asking a swine nutritionist to have a go at developing a new generation of diets.

Before new ingredients can be used effectively, some preparation is required:

Accurate information on energy and available nutrient content is required;

Processing and handling challenges must be understood; and

·Supply chain issues need to be clearly defined and managed.

While adding ingredients to swine diets can be financially rewarding, one must first ask whether the feedmill can even handle additional ingredients. And, although an ingredient may be a bargain today, we must ask ourselves how consistently it will be available.

Planning Required

The pricing relationship among a broader range of ingredients is constantly changing, so a new way of thinking is required to ensure we don’t end up with a feed bin full of an ingredient that is no longer economical to use compared to other ingredients available in the marketplace.

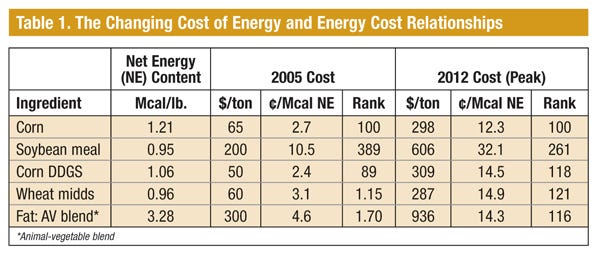

Therefore, longer-term planning and pricing and a different evaluation process is evolving. At the outset, the cost of energy needs to be tracked for all ingredients (Table 1).

Last summer, for example, a megacalorie (Mcal) of net energy from some fat sources was less expensive than the cost of energy from distiller’s dried grains with solubles (DDGS) — unheard of even a year earlier. However, we do not price DDGS strictly as an energy source, because it contains amino acids and available phosphorus as well.

The point is that the relative cost of energy from different ingredients is constantly changing, and it’s those changes that need to be understood or, ideally, anticipated.

Focus on Energy

Energy is the most expensive component of the diet, and we need to monitor and measure it differently in order to minimize feed cost and maximize net income.

Do you remember the old thumb rules: wheat is worth “X” if corn is worth “Y,” or soybean meal or wheat middlings are worth X% of corn? Those days are gone. There are too many variables to permit these simple thumb rules to work. If we continue to use them, we will miss out on some tremendous opportunities to improve net income.

Variables to consider are barn throughput and energy content of the diet, for example. If a farm’s diets have trended toward lower-energy diets, then wheat middlings — a low-energy ingredient — is of greater value relative to corn than when higher energy diets are fed.

It is incumbent on producers and nutritionists to look at all kinds of different ingredients and select those that make sense in their circumstances, all the while assuming that the goal is to achieve predictable animal and financial performance.

Following are a few alternative feed ingredients and the strengths and challenges of their use. Some have been considered “novel” dietary ingredients in some regions, but geographical limitations are beginning to dissipate.

Wheat

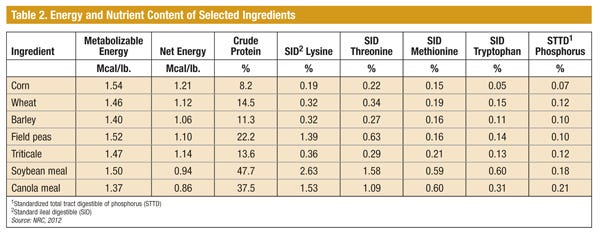

Wheat is a higher-energy ingredient, not quite as high as corn (Table 2), but a richer source of amino acids and available phosphorus. It is a common feedstuff in some regions and easy to process and handle for swine. Wheat can help improve pellet quality.

While typically grown for human consumption, specialty varieties, often lower in crude protein, have been developed in recent years for use specifically in animal diets. If durum wheat is being fed, care must be taken to avoid grinding the wheat too finely, which makes it less palatable (not a problem in pelleted diets). There is no reason to limit the quantity of wheat in a pig diet as long as overall dietary energy levels are met.

Barley

Barley is a lower-energy ingredient than either corn or wheat. It is richer in fiber and contains very little fat. While it contains less protein than wheat, it has almost the same levels of many essential amino acids. Like wheat, the energy content of barley can vary considerably, based on changes in soil moisture, heat and other environmental conditions.

Pig performance on barley-based diets will depend on feed intake. If pigs can eat more to compensate for lower energy, growth rate will be very good but feed efficiency will be reduced. However, if pigs cannot make this adjustment, then both growth rate and feed efficiency will suffer.

There is no reason to limit the quantity of barley in a diet as long as overall dietary energy levels can be met or pigs can reasonably be expected to maintain energy intake by eating more.

Canola Meal

Canola meal is a commonly used ingredient in many parts of the world, but not in the Corn Belt. Canola is typically, but not always, a dry-land crop. It is grown primarily for its oil, secondarily for its protein content.

Lower in energy and essential amino acids than soybean meal, canola meal often sells at a significant discount. Pricing relationships between canola meal and soybean meal can be quite variable, so canola might price in or out of a diet within a relatively short time span.

Much is made about the palatability of canola meal, but in my experience it is a very effective ingredient in pig diets. Dietary levels will range from 5% in later nursery diets to 10% in finishing diets. Dramatic increases in the dietary content of canola meal should be avoided due to its different flavor. There is no need to limit canola meal in gestation diets, but typically it is not fed at more than 7.5% of lactating diets.

Field peas

Field peas are another crop grown for human consumption, but excess supplies or lower-quality peas can make it into livestock diets. Field peas contain about the same energy as wheat, but slightly less than corn. They are a good source of essential amino acids, especially lysine, although they are not a good source of the sulfur amino acids such as methionine. Diets containing as much as 40% peas have proven to be highly effective when fed to pigs.

Field peas are highly palatable to the pig, but care must be taken to ensure they do not contain excessive levels of foreign matter. Harvesting peas can be a challenge because they are so low to the ground, which increases the odds of foreign matter ending up in the bin. Some pea samples can have up to 6 to 8% foreign matter. Good brokers will clean samples.

Triticale

Triticale is a hybrid of wheat and rye. As such, it has about the same quantity of energy as wheat but is somewhat richer in amino acids. Triticale also tends to be a dry-land crop, so energy content can fluctuate with growing conditions.

Because it is a close relative of rye, triticale tends to be more susceptible to ergot than wheat. Fortunately, contamination in the grain is readily identified with the naked eye, but unfortunately, it is not easy to clean triticale of ergot. Generally, some version of air segregation is needed because kernels with ergot are of a similar size to non-infested triticale, but less dense. Clean triticale can be readily fed to swine without problems, provided it is not ground too finely.

Ingredient Value

These are but a few examples of feed ingredients not commonly used in swine diets in the Corn Belt. Their value depends on pricing, accurately characterizing nutrient content and proper processing for the pig. The real deciding factor in their use is whether they offer a financial advantage in a feeding program.

You May Also Like