Though the financial situation is not good and no one likes losses, there have also been some encouraging signs this fall for hog producers.

December 6, 2016

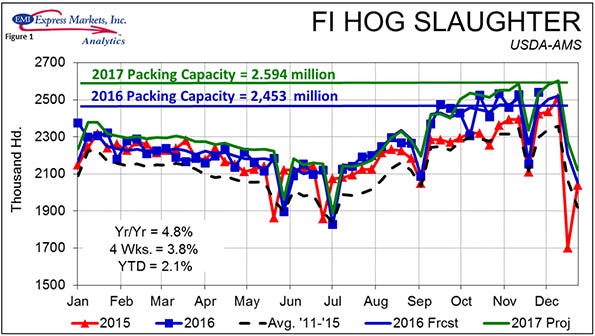

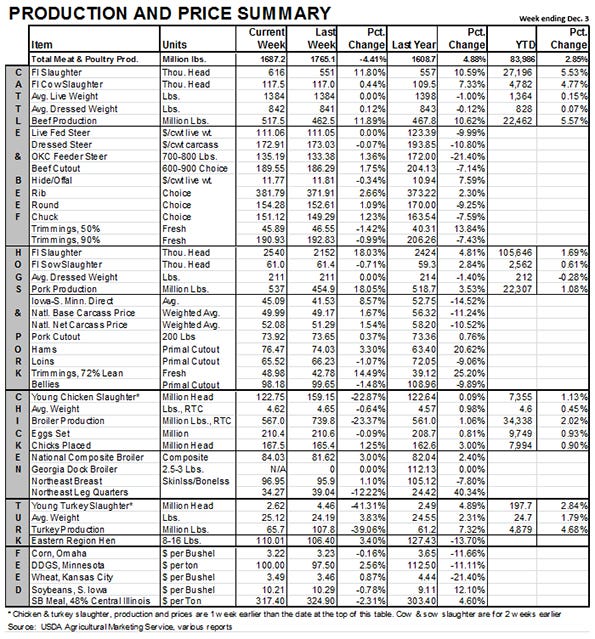

It is now a familiar refrain: Last week saw yet another record for federally inspected hog slaughter and pork production. The week’s total harvest of 2.540 million head is an all-time record and marks the fourth time this fall that more than 2.5 million hogs have moved through U.S. plants (see Figure 1). Pork production last week was also record high at 537 million pounds. There are plenty of pigs and pork available.Though the financial situation is not good and no one likes losses, there have also been some encouraging signs this fall.

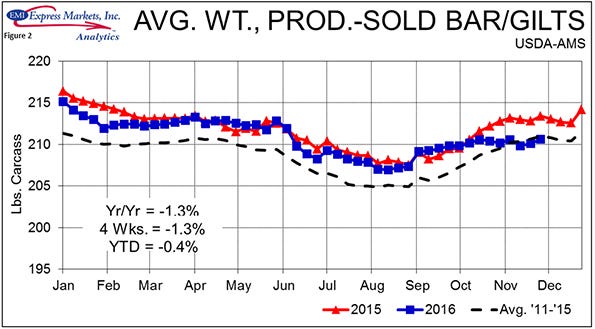

Producers have managed this situation about as well as they could have, keeping market weights basically flat since Sept. 1, and pulling 1% to 1.5% off pork production. Actual FI slaughter has exceeded our forecasts following the September Hogs and Pigs report by about 1.2% or 565,000 head. Those figures compare pretty well with market weights that are 2 pounds or so below what we expected, indicating that one to two days’ worth of hogs were pulled forward. Getting hogs gone was absolutely the best strategy both individually (why feed them longer when prices are falling?) and from an industry standpoint (to reduce supplies slightly and make sure there was room at plants for future pigs).

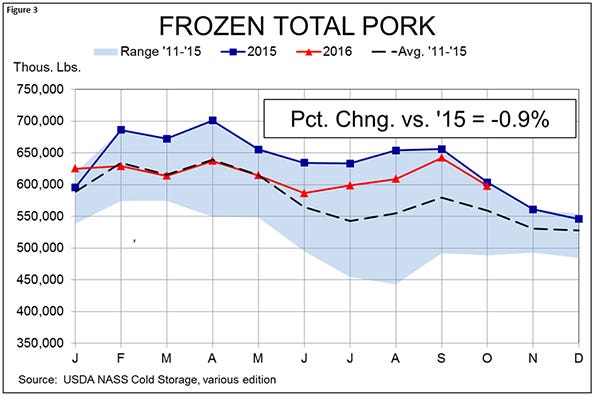

Second, movement of pork products has been excellent. We will not know the export data for November until January but all indications are that they will be good. I make that call primarily based on November cold storage data that indicated a larger-than-normal drawdown of pork stocks. The November decline in pork stocks was about 60 million pounds larger than normal for the month — at a time when production was setting records on a pretty consistent basis. Pork stocks are still only 0.9% lower than one year ago (see Figure 3), but the big story is that they are not larger. The same can be said of ham stocks — the item that often blows up inventories in the fall of the year.

Third — and perhaps most important — there was a rally in the negotiated market last week. And it was not small as the Iowa-Minnesota direct hog price gained over $3.50 per hundredweight or 8.5%. Now this price still only averaged $45.09 per hundredweight carcass for the week, but a rally during the week that slaughter and production set a record and very near the end of any holiday strength for hams is pretty noteworthy. The hogs in this negotiated price box are the ones most vulnerable to price pressure when plants are full since they don’t have a “home” when slaughter numbers grow. But they are also the ones that packers have to chase when they want to get more hogs to expand throughput or keep already-busy slaughter lines running at full capacity.

Producers are still not out of the woods on this price crunch as a lot of hogs are still coming. Our forecast for peak weekly slaughter is for the week before Christmas at 2.251 million head. That level has, of course, already been eclipsed but it is frequently a good bet for the seasonal peak. If we are correct about how current marketings are, and the idea that some hogs have been pulled forward, we may well have seen the peak last week. Let’s hope so. Any numbers below our forecasts for the rest of this year will, we think, push hog prices higher.

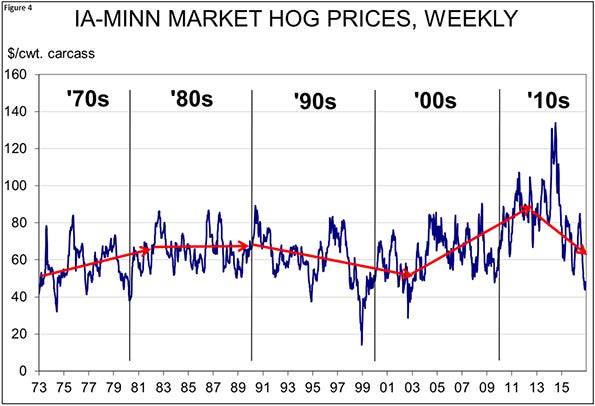

While working on another project this week I ran across a chart that I thought readers would find interesting. Figure 4 shows Iowa-Minnesota hog prices on a carcass basis back to 1974. Note that several different price quotes over the years were massaged a bit to make them as comparable over time as possible. Several trend periods are clear. The first is the inflation-driven trend of the 1970s. The next is a long period of flat prices around which we saw only seasonal and cyclical variation. The structural change of the ’90s and its constant lowering of costs of production is also apparent as is the ethanol-driven increase in feed costs of the 2000s. The 2010s has been a period of outliers if there is such a thing. First, droughts in 2011 (impacting primarily cattle) and 2012 caused forage and feed shortages that eventually pushed prices higher. The porcine epidemic diarrhea virus shortage — and scare — of 2014 was an outlier of immense proportions.

Prices since the PEDV epidemic have fallen well within what I think is “normal,” and that includes the prices we have seen this fall. They are certainly low relative to recent history but we should not be at all surprised by them. With costs in the mid-$60s and the prospect of them remaining there for the foreseeable future, we should expect some time periods of prices $20 or so lower than costs. In addition, the fact that they have stayed only about $20 lower than costs is a good indication that the industry is taking a more long-term look at itself and its future. Profit will not always prevail but there is enough for everyone in the long run if we mind our business tomorrow and the next day.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like