Packers know which loins are good and can sort them to high-value markets. They even know whether more of those loins come from particular lines of hogs or particular producers.

December 4, 2017

When I started my pork industry career in 1991, a high-quality hog meant one thing: A lean hog. The reason, of course, is that there were not very many such critters around. Chicken had charged into a health-conscious marketplace with “lean protein” which was, in addition, lower in cost and put the hurt on pork and beef products that consumers suddenly viewed as too fat and even dangerous.

The National Pork Producers Council had recently released its Lean Value Guide to Hog Buying which proposed premiums and discounts based on fat thickness carcass weights. USDA had a carcass grading system that was antiquated to say the least since even the relatively fat hogs of the early 1990s were far leaner than those of the ’70s when the system was last revised. Packers offered premiums based on grade and yield which were, in fact, simply payments for the amount of carcass that the packer bought with the “premium” derived by comparing the actual payment to a contrived standard live value that was too low because packers’ standard yields were too low. Packers claimed that they were already paying for the good hogs and producers should be happy about it.

The proposed system was radically different. Packer uptake on the idea was, to say the least, slow. In my opinion, part of that reticence was defensiveness but part of it was legitimate. The defensive part was twofold. First, packers didn’t care much for producers telling or even suggesting to them how to run such an important part of their business. Second, packers already knew who had the good hogs and were not being forced to pay any extra for them. Why would they want to adopt a system that made them do so?

The legitimate objections dealt with measurement methods, accuracy of those measurements, correlations between the measurements and actual carcass value, and taking accurate measurements at chain speed. Good solutions didn’t exist for all of those concerns.

But the market was clearly telling packers that they must deliver lean pork products and getting such products from fat hogs was expensive. It took a lot of labor and resulted in a large pile of fat that had a value near zero.

When a couple of packers developed their own version of the Lean Value Guide and started paying premiums for lean hogs and penalizing fat hogs everything changed. Not only did those packers begin buying a higher percentage of lean, high-value hogs and improving their product offerings while reducing that pile of near-zero value waste, but their competitors by default began buying fewer of those lean, high-value hogs. The competitive landscape changed quickly and, voila, hogs began getting better.

Why do I go through all of this? Another such moment may be upon us. USDA has formally proposed a voluntary quality grading system that would classify pork carcasses and cuts into Prime, Choice and Select grades such as has existed for beef carcasses for many years. I believe there is good reason to take action and it is the flip side of the leanness success story outlined above.

When the industry finally had a reason to focus on leanness, it did so with a sharply focused, steely eyed vengeance. Percent lean became the holy grail of breeding companies, nutritionists and producers. Fat disappeared and muscling improved. The gains from price premiums were important but they proved a pittance compared to the efficiency of these animals that converted feed into lean instead of fat.

But single-trait selection gets single-trait improvement. Further, any trait that is negatively correlated to the target trait will, not surprisingly, move the other direction if no attention is paid to it. Leaner hogs have led to hogs with lower-quality lean and it appears to me that there has been a price to that change.

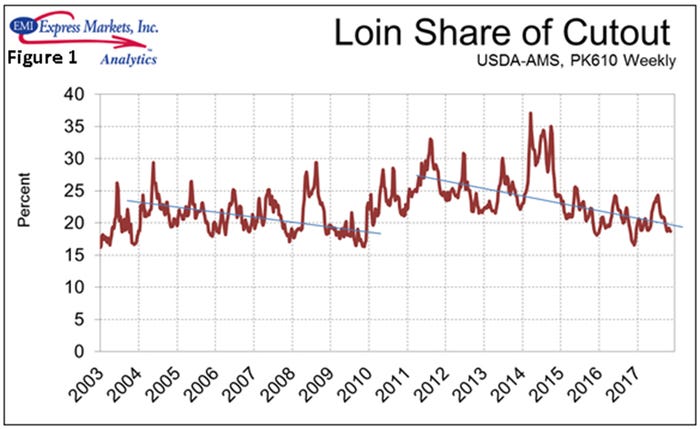

Loins have been a drag on hog value for years. What should be our flagship cut — think of ribeye, New York strip, T-bone steaks — has been anything but. As you can see in Figure 1, the share of USDA’s estimated cutout value accounted for by the loin primal fell steadily from 2004 through 2010. After a two-year improvement, it began to decline again in 2011 and, except for 2014 when large inventories of frozen bellies and ribs pre-empted their participation in the “porcine epidemic diarrhea rally”, the loin’s contribution has again fallen steadily from 26.86% in 2011 to just 20.65% so far in 2017. I believe former National Pork Board colleague John Green accurately stated a major reason for this decline: Pork loins and loin cuts are simply too risky for the average cook. The lack of moisture holding capacity and marbling in today’s loins make the probability for failure high enough that consumers simply avoid them.

My wife faithfully buys Brand X frozen sausage patties, Brand Y franks and Brand Z deli ham. Why? Because she knows that those names go with consistent characteristics that she and I like. That’s the reason for branding — consistency and communication. A number of industry studies have found that fresh pork in general and pork chops in particular lack both of those. So how can we extract more value from cuts that are not bringing “brand-minded” consumers what they want?

I don’t know if USDA’s proposed grading problem will solve these problems or not but several studies cited by the USDA in its federal register filing suggest that it might. In addition, other studies show that very high percentages of the loins presented for sale in retail meat cases are in the lowest categories for both color and marbling. It doesn’t seem to me to be the consumer’s fault that he/she won’t pay more or even buy a poor-quality product.

This will not be easy. Look at the parallels. The grading system is antiquated. Packers know which loins are good and can sort them to high-value markets. They even know whether more of those loins come from particular lines of hogs or particular producers. Measurement systems are in their infancy. There are big questions as to whether the measurements can be done at line speed. Can you see the parallels to the lean value proposals of the late-’80s and early ’90s?

Like then, packers say that they are already paying producers for higher-quality lean. And they might be. But a premium that isn’t visible doesn’t drive change. Neither does a discount whose cause isn’t explicit. There is evidence that consumers see value in meaningful grades. There is even evidence that some consumers think the worse grade is better product suggesting that discounts may not be required to sell Select-grade or no-grade pork. It may only require savvy positioning and merchandising.

Like in the ’90s, it really boils down to one question: Who will lead? Producers have done their part through Checkoff-funded research that has identified an opportunity. Who will be the first to grasp the opportunities?

USDA’s Agricultural Marketing Service invites the public to comment on the proposed revision to the U.S. Standards for Grades of Pork Carcasses. Comments may be posted online at Regulations.gov, submitted by email to [email protected], or sent to: Pork Carcass Revisions, Standardization Branch, Quality Assessment Division; Livestock Poultry and Seed Program, AMS, USDA; 1400 Independence Ave., SW.; Room 3932-S, STOP 0258; Washington, D.C. 20250-0258.

Comments received will be posted without change, including any personal information provided. All comments should reference the docket number (AMS-LPS-17-0046), the date of submission, and the page number of the issue of the Federal Register.

Comments must be received by Dec. 22.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like