The U.S. hog industry has been battling porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome for nearly 30 years. The virus has proven to be non-discriminatory across all ages of pigs, causing great economic impact. The key to eliminating, or at least reducing, the impact of the PRRS virus is to build herd immunity to the viral challenge to which pigs may be exposed.

To achieve that level of herd immunity, producers and their veterinarians need to properly utilize all tools available in their tool box, and researchers have labored over studies to help provide applicable tools and solutions.

Reid Philips, PRRS technical manager at Boehringer Ingelheim Vetmedica Inc., says past BIVI research, both controlled studies and in the field, has addressed heterologous cross-protection benefits of modified-live virus vaccine both in sow farms and growing pigs.

“People want to know: ‘Will the PRRS vaccine protect my pigs against the various strains of PRRS virus circulating in the U.S swine population?’” he says. Philips says a number of challenge and heterologous protection studies have been performed and in each of those a direct benefit of vaccine-derived immunity has been demonstrated. “That means pigs that have vaccine-derived immunity and were subsequently challenged with heterologous or wild-type PRRS virus isolates demonstrated a reduction in viremia, reduction in PRRS-induced lung lesions, reduction in fever post-challenge and improvement in average daily gain,” he says. “To sum that up, vaccine-derived immunity mitigates the consequences of infection — ultimately improving health and performance.”

Philips says that’s what producers and their herd veterinarians want: a vaccine that will mitigate the effects of the viral challenge.

Other studies have shown that an indirect benefit of the vaccine across a swine population is reduced virus shedding, or a reduction in the amount of wild-type virus circulation within and between vaccinated populations. “That’s a good thing. We want to reduce the level of virus and keep it down, to reduce the risk in pig-dense, high PRRS-prevalent regions,” Philips says.

Next step

With that information in mind, Philips says the next logical question was: Is there a challenge dose effect in vaccinated pigs? In other words, if we reduce the virus level over time by maintaining uniform immunity within and between populations, is there a level of challenge virus dose where the consequences of challenge in vaccinated pigs are made inconsequential?

Philips says his team found that there had been minimal research done to that effect so a study was designed to answer this question

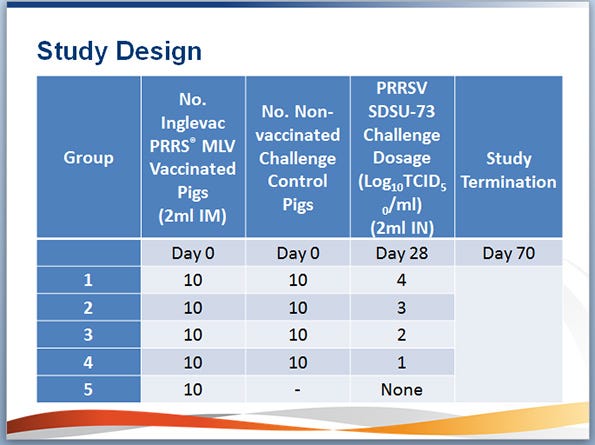

“We looked at various levels of challenge in vaccinated and non-vaccinated pigs to evaluate the effect of challenge dose in pigs with vaccine derived immunity,” Philips says. There were actually four levels of PRRSV challenge doses administered in this study to mimic the variation of challenge doses in field conditions.

BIVI recently presented this research project that included 90 piglets that were three-weeks-old at the start of an experiment. Four vaccinated groups, with 10 pigs per group which were matched with four non-vaccinated groups. The pigs, originating from a PRRS-naïve source, were confirmed to be PRRS-negative by polymerase chain reaction test. Pigs in each of the four groups were vaccinated with Ingelvac PRRS MLV, BIVI’s MLV vaccine at Day 0. One group of 10 pigs served as vaccinated and non-challenged controls. The vaccinated and non-vaccinated groups were housed separately to avoid potential cross-infection during the vaccination stage of the study.

“You must prevent transmission between the various treatment groups to maintain group integrity,” says John Waddell, BIVI senior professional services veterinarian.

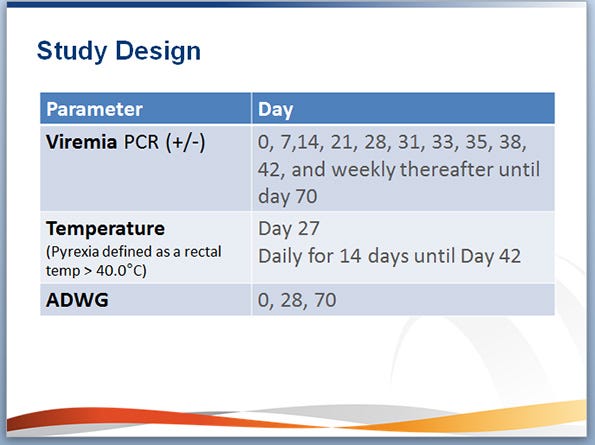

On Day 28, groups 1-4 were challenged with 1.0 milliliter per nostril of virulent PRRSV SDSU-73 inoculum which is a highly virulent U.S. PRRS isolate. Challenge doses of the PRRS virus were at four different levels, 1 log through 4 logs, with 4 logs being the highest dose challenge. “Intranasal routes best mimic the natural transmission that occurs in the field setting, as pigs within a population would be exposed to the virus by breathing in air infected by positive pigs shedding into the environment,” Waddell says. A control group was vaccinated with BIVI’s MLV vaccine and was not challenged by the PRRSV strain. Blood samples were taken from all pigs on days 0, 7, 14, 21, 28, 31, 33, 35, 38 and 42, as well as weekly after that until day 70 to assess viremia and serologic response. Viremia was tested using quantitative PCR.”

A control group was vaccinated with BIVI’s MLV vaccine and was not challenged by the PRRSV strain. Blood samples were taken from all pigs on days 0, 7, 14, 21, 28, 31, 33, 35, 38 and 42, as well as weekly after that until day 70 to assess viremia and serologic response. Viremia was tested using quantitative PCR.”

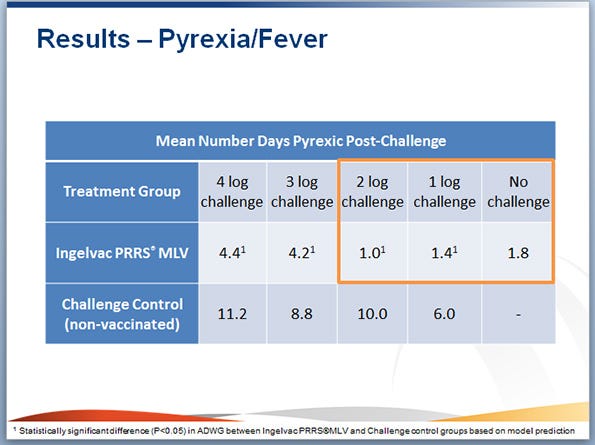

Rectal temperatures were collected on Day 27, and daily for 14 days until Day 42. Temperature readings greater than 104 degrees Fahrenheit were defined as pyrexia (fever).

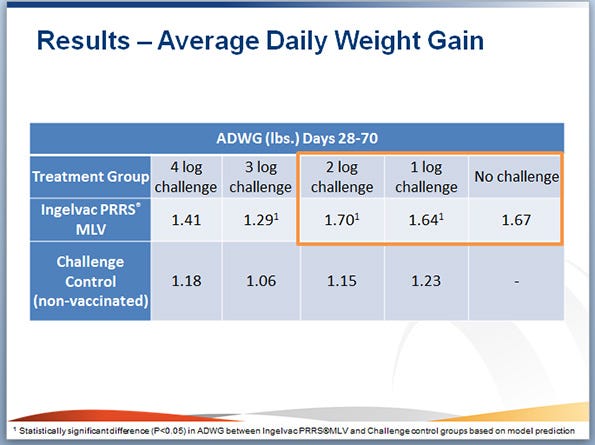

Pigs were weighed at Day 0, Day 28 (when the pigs received the PRRSV challenge) and at the termination of the study on Day 70, to determine average daily weight gain.

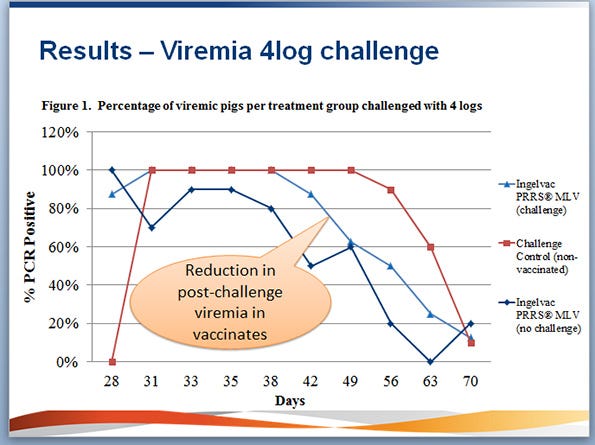

All pigs in the MLV-vaccinated treatment groups that received the 4 log and 3 log challenge became viremic by Day 31. At 14 days post-challenge, viremia in these pigs began decreasing through to the end of the study at day 70. From Day 42 to Day 70 of the study, the vaccinated pigs in these two groups showed a lower percentage of PCR-positive pigs than the non-vaccinated challenge control pigs in groups challenged with 4 and 3 logs of virus, indicating a reduction in post-challenge viremia in vaccinated pigs.

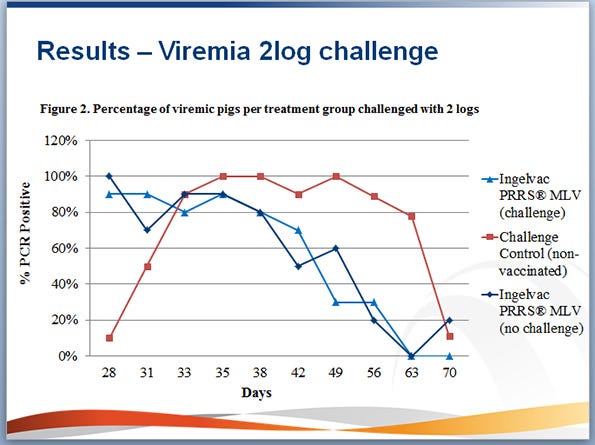

MLV-vaccinated pigs in the groups getting 2 and 1 log challenges demonstrated a lower percent PCR-positive pigs than the non-vaccinated challenge control pigs. The viremic pattern following the challenge in the vaccinated groups that received 2 and 1 log challenge was similar to the vaccinated non-challenged pigs in group 5. As the challenge dose decreased, the percentage of viremic pigs in the vaccinated pigs in the vaccinated groups decreased. At all challenge doses, non-vaccinated and challenged pigs showed similar post-challenge viremia profiles.

Immunity at all levels

“Interestingly, what we found was that at any challenge level vaccine-derived immunity was important,” Philips says. “At any level of infection, from 4 logs down to 1 log, we mitigated the consequences of infection as measured by viremia, fever and average daily weight gain. In other words, at any level, vaccinated pigs versus non-vaccinated pigs had fewer fever days, less viremia post-challenge and had better average daily weight gain post-challenge. From prior studies, that would be our expectation, that PRRS MLV vaccine would mitigate the consequences of infection.”

Interestingly though, Philips says at the lower levels of challenge — 2 logs or less — the vaccinated pigs performed similar to the pigs that weren’t challenged at all when looking at the same criteria of viremia levels, fever and average daily weight gain. “The findings were interesting,” he says, “and that they support the hypothesis that at lower levels of challenge, vaccine prevents the consequences of infection, and in some cases it is as if the virus challenge didn’t happen at all.” What does this mean for producers?

What does this mean for producers?

Philips sees the potential that, if uniform vaccine-derived immunity can be achieved in high-risk, high-density, high-PRRS prevalent areas within and between hog populations, we will reduce the amount of shed virus over time. “Then we should be able to drive the resident virus population down to more-manageable levels, potentially to the lower-challenge levels as evaluated in this study.”

Waddell agrees, suggesting that producers in PRRS-prevalent areas with dense hog populations, such as the Midwest, would be well-served to use these findings as a reason to vaccinate to establish and maintain herd immunity.

Findings of this study, suggest that at low levels the consequences of virus challenge in vaccinated populations become less impactful. Philips feels the findings support targeted and strategic PRRS vaccination and management protocols at the farm level or a system-wide approach, and even regional control areas.” Vaccination programs themselves aren’t the silver-bullet, Philips reiterates. “Ingelvac PRRS MLV is just one of the tools that we have at our disposal,” he says. “It is an effective tool, but for optimum PRRS control and management, it’s not vaccine alone. It’s effective vaccination protocols along with other complimentary components that are important for PRRS control including biosecurity, pig flow and other health management tools and technologies.

Vaccination programs themselves aren’t the silver-bullet, Philips reiterates. “Ingelvac PRRS MLV is just one of the tools that we have at our disposal,” he says. “It is an effective tool, but for optimum PRRS control and management, it’s not vaccine alone. It’s effective vaccination protocols along with other complimentary components that are important for PRRS control including biosecurity, pig flow and other health management tools and technologies.

“I think PRRS, and more recently PED, have really ramped up the idea of how important biosecurity is in our industry within and between pig populations,” he says. “The best programs utilize all tools in the tool box. Immunity matters, but immunity with biosecurity, health management strategies and pig flow, make for sound PRRS control.”

Takeaways

Philips and Waddell point to three key takeaways from this research:

At all challenge doses, vaccination mitigated the consequences of infection — reduced viremia, reduced fever and improved ADWG compared to non-vaccinated (non-immune) pigs.

In lower challenge doses, 2 logs or less, the consequences in vaccinated pigs were the same as non-challenged pigs.

At any level of challenge (1 log to 4 logs) the impact in non-vaccinated (non-immune) pigs is significant as measured by average daily weight gain and viremia.

Philips says that understanding the current status of a given population as well as the types and levels of risk for PRRSV is an important early step in developing PRRS control strategies. Philips says the presence of other pathogens or co-infections also play a role in how pigs respond to PRRS challenges, “and that is why it is so important to manage immunity relevant to PRRS and the other potential co-infection pathogens such as mycoplasma, influenza and circovirus, in an effort to best mitigate singular pathogens as well as if they occur as co-infections.”

Waddell says that many questions have been answered in the nearly 30 years of PRRS battle, “but new questions keep arising. This research just gives us more information to help fight this pathogen. This helps us fill in the blanks, as well as well as solidify some of our previous thoughts.”

As researchers and the industry learn more about PRRS, “we have reduced the impact of the virus and shortened the duration of the virus effect on the farm. We’re gaining, we’re making progress. This research is one tiny piece of the pie. We have filled textbook volumes with work on PRRS. Every little building block helps. PRRS has been, by far, the most challenging disease that the industry has endured,” Waddell says. “It has changed the way the industry raises pigs.”

He says that the difficulty in battling PRRS is that the virus and its effect on pigs is so variable. “When it comes to PRRS, no single protocol or plan will fit every farm and situation. It is very important to work with your veterinarian to develop a customized and comprehensive control strategy that fits each unique farm and situation.”

With that in mind, producers need to stay vigilant in their defense against PRRS

“It must be a comprehensive and systematic approach to understand the status and role of PRRS in a herd or farm and we know that immunity can play a major role to mitigate the consequences of PRRS,” Philips says.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like