Group sow housing takes a different mindset. When it comes to handling sows not in gestation stalls, the caretaker’s approach needs to be adjusted.

March 13, 2018

Group sow housing creates the opportunity to think differently about caring for and handling sows. Before converting to an open pen system, producers often look at barn logistics such as pen design, square footage, feeding system and equipment placement. The type of housing used for sows is a decision each farmer in the United States must make, weighing all the factors, including what system is right for the sows under his or her care.

For farms selecting group sow housing, the economic factors are easy to pencil. However, the new management style or adjustment of production practices takes a different mindset. When it comes to handling sows not in gestation stalls, the caretaker’s approach needs to be adjusted. Veterinarian Jessica Risser, Animal Health and Welfare manager for Country View Farms, an entity of Clemens Food Group, says successful group sow housing comes down to people.

Clemens Food Group started discussing a change in sow care in 2001, and in 2006 the company partnered with the University of Pennsylvania to investigate sow housing options. The first barn converted on the company’s farms opened in 2007, with the goal that all its farms, along with all Clemens Food Group suppliers, would make the conversion by 2022.

Risser says Clemens Food Group wants to enhance animal care by allowing sows to turn around, move around and socialize with other sows while they are in gestation.

It’s all about the people

Risser admits the facility design for group sow housing is ever-changing. Each barn, whether converted or built new, contains tweaks to facility features based on a lesson learned. Still, Risser says how the employees handle the transition is key. “People and management are the most important thing. The facilities issues can be worked out, but you must have the right people and the right knowledge for the team,” she told the Tri-State Sow Housing Conference.

As more employees hired at Country View Farms come with no background in animal production, Risser says teaching basic animal husbandry skills is a priority. These skills are essential in managing sows in a group setting.

In an individual gestation stall production system, the sow that workers care for the night before is right where they left her. With the feed and water in front of her, it easy to tell exactly what she has eaten and drunk. However, in the open pen situation, the team needs to decide how to monitor feed and water intake.

While an electronic feeding system provides data on individual feed and water consumption, a competitive feeding system requires observation to identify non-eaters. Even though a farm uses technology to identify non-eaters, people must find the non-eating sow and determine why she did not go through the feeder.

For group sow housing, Risser says they must continuously retrain team members in observation skills. Each employee working with the sows needs to be able to identify early clinical signs for an animal going off feed or not feeling well.

Team members also need to be educated and trained on the biological needs of the sow. Risser says they need to understand why sows are not mixed at certain times to avoid pregnancy loss and minimize fighting.

Risser recommends taking special care in selecting employees responsible for gilt training. It takes a special person to train gilts. Country View Farms has dedicated team members to gilt training. “It is their job. We have to interview specifically for that role because we need a patient, steady person,” she says.

Still, safety is always a high priority in the barns. Where group housing gives sows freedom to move, it also creates unsafe situations for animals and people. During the learning curve, Risser admits higher incidences of safety issues occur in open pens. For example, obtaining blood samples from a sow not in a gestation stall takes more hands and different skills. When she draws blood from sows in group housing, it takes an extra person to snare the sow and another person to stand guard with a sort board, safeguarding a veterinarian from being attacked from other sows protecting their friend.

“You just have to be aware and rethink how many people it’s going to take to complete the process because of the safety concern,” Risser says.

She further stresses it is people, people and people.

“It is retraining, management and providing knowledge,” Risser says. “Awareness, desire and knowledge are things we continuously go back to, to make sure our team members understand the whys of our processes.”

Low-stress sow handling

To some extent, handling techniques for sows in open pens incorporates skills used in grow-finish units. In simple terms, working with sows in a more open setting is the same as handling any large pigs in a pen. It is common sense to understand that if a person approaches a pig in an open area, the pig is going to flee.

Nancy Lidster, speaking at the Tri-State Sow Housing Conference, said pig caretakers need to quit using fear and physicality to move hogs.

She and her husband, Don, were commercial hog farmers for 20 years in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan before spending the past two decades training pig caretakers on the best practices for low-stress handling techniques.

Effectively handling pigs is about reducing stress for the animal by understanding animal behavior.

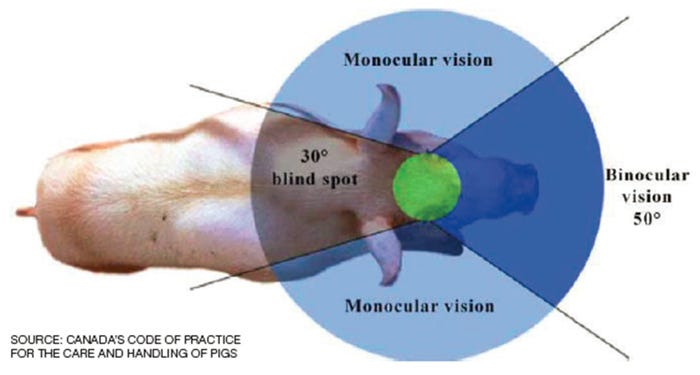

Lidster says many training documents used in the pork industry, such as Canada’s “Code of Practice for the Care and Handling of Pigs,” emphasize the flight zone and point of balance model to describe pig behavior.

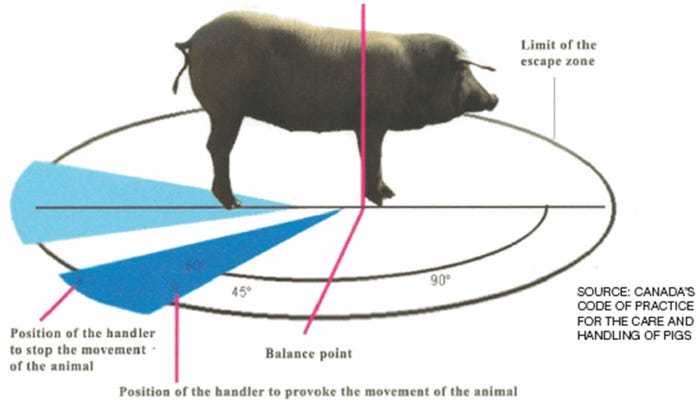

The model, introduced by Temple Grandin in 1979, was originally designed for a single cow moving through a curved working chute system. Over time the model was adjusted for a single pig moving through the same curved system (refer to Figures 1 and 2). The model assumes the pig is walking in a chute system, preventing it from turning around, and the handler is entering into the flight zone. A hog farm designed to move pigs in a circular curve corral system with working chutes is probably a rare find.

Figure 1: Monocular and binocular vision zones of the pig

Figure 2: Balance point of the pig: If the intention is to move the pig forward, the animal handler should be situated at Point B.

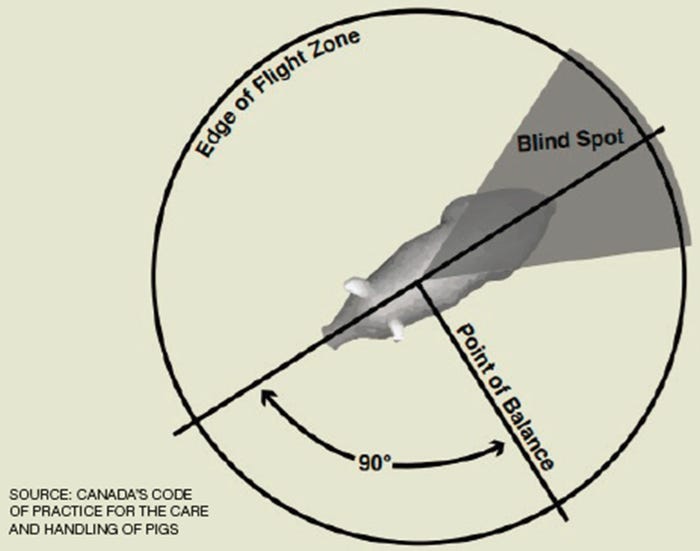

Still, the problems with the model are bigger than the curve chute system. Lidster explains the model is based on the concept that the pig’s point of balance is at the shoulder, and if the handler is behind that point, then the pig will move forward. Also, if the handler is in front of the pig, it will stop or back up.

Basically, it is based on the traditional concept that an animal will move in the opposite direction from a person no matter how the animal is approached. The model does not take into account handler pressure such as crowding pigs, physical contact and making noise that draws the pigs’ attention back to the handler rather than moving forward.

“We get the same results if we are too close, too aggressive, and not giving them time and space as we would get if we had something ahead of them stopping them,” Lidster says.

If pigs become uncomfortable, they slow down and often stop. Unfortunately, people have forgotten a valuable part of the lesson taught by Grandin. “You have to work at the boundary of the flight zone. It is real, and people have to recognize where it is and respect them,” Lidster says.

Watch the ears

Paying attention to body language and recognizing if animals are scared or what grabs their attention is the only way to influence herd behavior. “The sad part is, we have people thinking the animal is stopping because of something up there, when in fact, it is me back here doing stuff to it,” Lidster says.

The Lidsters teach handlers to think about a safe zone or a bubble being around themselves as an alternative to a flight zone. “It is easier to see the relationships of the interaction if we look at it in terms of the bubble around the handler,” Lidster says.

She explains that the size of the bubble varies. The bubble gets bigger as pigs become more afraid. If things change, the distance can increase dramatically in the blink of an eye. It also differs from one pig to another. “When pigs get too scared, the bubble gets bigger. They pay close attention to us, and their behavior changes,” Lidster says.

A pig’s natural tendency when a person enters a confined space is to move back and then circle. Animals want to keep track of humans, and therefore respond by circling. If workers enter that space with the expectation the pig is going to move away but it actually circles, then you end up in a fight situation, Lidster says.

To move a group of sows, Lidster says rather than push the entire group toward the gate, it is more effective to stay at the side and ask the animal to move past you.

Nevertheless, it does not matter if you move one sow or a group, the body language of the animal tells the tale. When the head and ears are cocked, you can tell the direction of the sow’s attention. It is essential to let the sow take a few steps forward before you begin following, especially if her ears are already up.

The Lidsters always perform tasks such as vaccination or medical treatment in large pens of pigs without isolation. The body language of the handler highly influences the pigs’ behaviors. It is about trust between human and pig. Pig handlers need to be aware of the animal’s body language. If a person acts too quickly or aggressively, the animal becomes stressed.

The other side of body language is swine politics. If a handler tries to move a sow past another sow and it does not want to interact, the animal must be given an alternative path.

Overall, Lidster says handling sows in a group setting isn’t really any different than handling a group of finishers; however, certain management techniques need to be avoided, including pushing and chasing.

She offers these handling tips:

• All handlers need to start with the same core values in handling pigs.

• When training gilts or sows in a new environment and feeding system, it is best not to push a sow or gilt into the feeder. Training takes calm, quiet and patient handlers.

• Everyone must be aware of what is going on during pig movement.

• Sufficient distance between humans and pigs needs to be maintained at all times.

• Know what is normal. When entering the barn, know what the normal noise level is. What is the normal behavior in an electronic sow feeding system?

If you take one thing away from Lidster, it is “watch their heads and not their butts.”

“It is in their heads; we see what they are paying attention to. It is their heads if their excitement level is rising,” she says. “It is sort of the combination of those two things that we can anticipate what is going to happen in terms of herd behavior. Are we going to get herd behavior that encourages them to move and flow together, or are we getting herd behavior to clump up and refuse to move?”

Pork Quality Assurance Plus updates the model, as seen in Figure 3, and discusses other pig handling techniques in the handbook (refer to the story below).

Figure 3: Pork Quality Assurance Plus updated figure shows the flight zone, the point of balance and the blind spot of an individual pig.

Understand pig body language

Pigs show what they are paying attention to with body language — specifically their heads, eyes and ears. Handlers should note where pigs are looking, how they are bending or twisting their bodies, how they have their heads and ears turned or cocked, and whether they are listening intently.

Pigs track their handlers more closely as the handlers become more threatening, the pigs become more stressed, or the space they are in becomes more confined. In confined spaces or when pigs are stressed, a handler’s pressure tends to hold pigs’ attention rather than drive pigs away. However, when pigs become highly agitated, they may tightly bunch and refuse to move.

Pigs’ body language changes as they go from calm to highly excited. A good animal handler can read this body language and adjust his or her actions accordingly.

Releasing pressure refers to any action that reduces the level of threat posed to the pigs. It often involves giving pigs more time and space. Some ways to release pressure are to:

• Pause and let pigs move away.

• Step back and refrain from making physical contact with pigs.

• Soften handler body language to reduce the threat, and therefore the distance the pigs will require.

• Let pigs circle past (the strongest pressure is in the direction the handler is facing).

• Discontinue making noise.

• Look away from the pig.

• Reduce group size. The proper group size depends on several factors such as pig size; width of aisle, door or chute; and environmental influences.

Pigs communicate their level of fear with their heads, eyes, ears and body movements.

Pigs that are calm are able to stay a safe distance from the handler and get release from the handler’s pressure. Calm pigs do the following.

• hold head and ears low with body relaxed

• move at a walk or trot, with exuberant outbursts if excited but not scared

• focus attention mostly forward

• may have low-pitched vocalizations

Pigs show mild fear or defensiveness because the handler is getting too close or not giving enough release from pressure. These pigs do the following.

• have raised heads and ears

• move away but with increasing attention toward the handler

• have an expanded flight zone

• exhibit a possible brief increase in speed

• will calm down if pressure is released

• will become fearful or defensive if pressure is maintained or increased

Pigs show heightened fear or defensiveness because the handler is too close or using too much pressure, and the animal is unable to get release. Pigs feeling heightened fear or defensiveness do the following.

• give full attention to the handler

• stop, back up, turn back or try to get past the handler because efforts to move away aren’t working

• shut down and refuse to move, which is a defensive response different from being too tame or fatigued

• bunch up and are difficult to sort or separate

• will calm down after some time if pressure is released

• will escalate to extreme fear if pressure is maintained or increased

Pigs show extreme fear or defensiveness when they are unable to get release from the handler. These pigs do the following.

• panic

• run under, over or through handlers and obstacles

• scramble and show out-of-control movement

• have high-pitched vocalizations

• bunch up and are difficult to sort or separate

• show severe stress symptoms which may lead to death

You May Also Like