Increase in U.S. sow mortality a real mystery

When a sow is culled or dies within two weeks before or after farrowing, it can be extremely costly. This is a common occurrence reported among many U.S. producers and not isolated to a certain region or production models.

Hog producers and swine professionals gathered for the DSM Pork Nexus at North Carolina State University to discuss one thing — why are sows leaving the farm way too soon? A noticeable trend among hog producers around the globe is a steady climb in sow mortality, particularly in the past three years.

As Jerry Torrison, DVM, director of veterinary diagnostic labs at University of Minnesota, says, “All sows are created equal, but some are just more expensive.”

When a sow is culled or dies within two weeks before or after farrowing, it can be extremely costly. This is a common occurrence reported among many U.S. producers and not isolated to a certain region or production models.

Doing the quick math, Jeremy Pittman, DVM at Smithfield, calculates 1% sow morality equals 22 cents per weaned pig, assuming the loss of cull revenue only; 50 cents per pound and 22 pigs per sow per year. However, he asks, “What is the true full cost?”

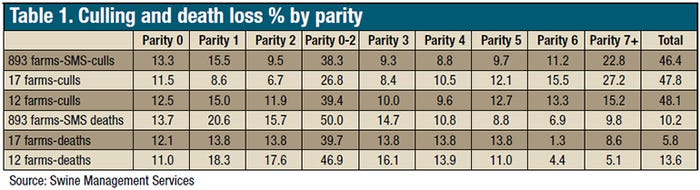

The rising trend in sow mortality or early sow culling is not just shop talk. It is becoming quite evident in the benchmarking data. Ron Ketchem from Swine Management Services says a 12-year data set shows sow death loss from 2013-2016 has risen from 5.8% to 10.2% on farms owning 125 to over 10,000 sows in the SMS database. Ketchem says, “This makes you wonder what has changed in the last three years.”

While all sizes of operations in the SMS data are experiencing this noticeable increase, sow farms with 2,000 to 3,999 head had a higher female culling and more deaths. Moreover, the higher deaths and culls are coming from younger parity females. According to the data, “Almost 50% of the deaths were coming out of parity 0-3 and 40% of the culls in the first parity,” notes Ketchem.

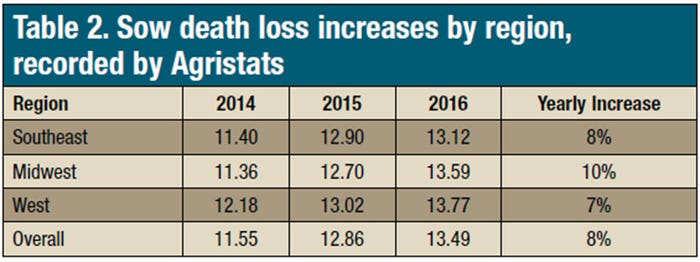

The trend is not limited to the farms in SMS database. Brent Frederick, Christensen Farms director of research and nutrition, verifies that the linear increase is real among farms participating in the Agristats program, which includes some of the largest U.S. pork producers with more than 100,000 sows in production, with different genetic packages, feeding programs and regional locations. “Sow morality within this data set has increased linearly from January 2013 to date. The increase in mortality is consistent across the U.S. and not an isolated regional issue.”

While the rise in sow mortality is noticeable and generating healthy discussion, the reason for higher rates of cull and sow mortality is still a mystery. The results of diagnosed causes for sow death at the University of Minnesota diagnostic lab range from accidents to structural problems to respiratory events to reproductive issues.

The occurrence of lameness and prolapses comes to the top for causes of early removal of females from the herd. The removal for lameness related reasons is greater in parity 1 and 2 females. “Lameness looms large as for the cause of removal of young parities,” states Torrison.

Breeding gilts or sows that are lame or have a structural issue is only asking for trouble and will end up costing a farm dearly down the road. So, a full evaluation of a female’s structure and lameness detection before breeding can diminish future problems and save the farm money.

An increase in the number of sow prolapses is contributing to sow deaths as females are euthanized due to animal welfare policy. Pittman says historically the natural incidence of sow prolapses is rare, estimated at a 0.5% to 1.0% annualized rate. In December 2012, Pittman was observing a surge in sow prolapses in the Smithfield system and dealt with it for a year and a half until Max Rodibaugh, DVM, presented the problem in an article in the August issue of National Hog Farmer. After a group discussion at American Association of Swine Veterinarians meeting, it was clear that it was an industry problem. “What is interesting is a sporadic event where a farm over the course of one to three weeks has an increase in the number of prolapses — can be very high at times — and then it goes away for a period of time, then comes back,” explains Pittman.

In the industry, Pittman says there has been a step change in the percentage of annualized sow mortality due to prolapses occurring on an annual basis from 2013 to 2016. For his region, Pittman reports there was a linear increase from 1.8% in 2012 to 2.9% in 2016 in a group of 105,000 sows with a massive change from 2012 to 2013. “It is not just the fact there is a prolapse. The severity and extent of these prolapses are greater,” notes Pittman.

The frustrating part for Pittman and others in the swine business is there is no one real reason for the rise, nor is there a one-size-fits-all solution. In fact, Pittman says numerous causes of prolapse have been discussed in the industry. They include:

■ mycotoxin in feed

■ hypocalcemia

■ vitamin deficiency

■ use of phytase in sow rations

■ litter sizes

■ constipation

■ genetics

■ change in estrogen and other hormone levels

■ oxidative stress

■ impact of changing to mash feed

■ high and rapid feed intake

■ bloated sows

■ coughing

■ piling

■ housing design

■ diarrhea, colitis

■ excess lysine

Today, there is still no clear answer, and an industry task force has been formed to address the issue. “Something changed in the industry. It is clear there are a lot of systems and sows affected by this,” concludes Pittman.

Although no one attending the Pork Nexus meeting has the reason or the solution to the upsurge in the number of females leaving the swine herd early, the problem is real, and the discussions are getting more serious as the industry works toward finding the answer.

Like Torrison advises, “A dead sow is a gift; you should open her up.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like